Opinion A magisterial probe

Chilcot report unflinchingly challenges the UK’s Iraq policy, setting an example for democracies everywhere

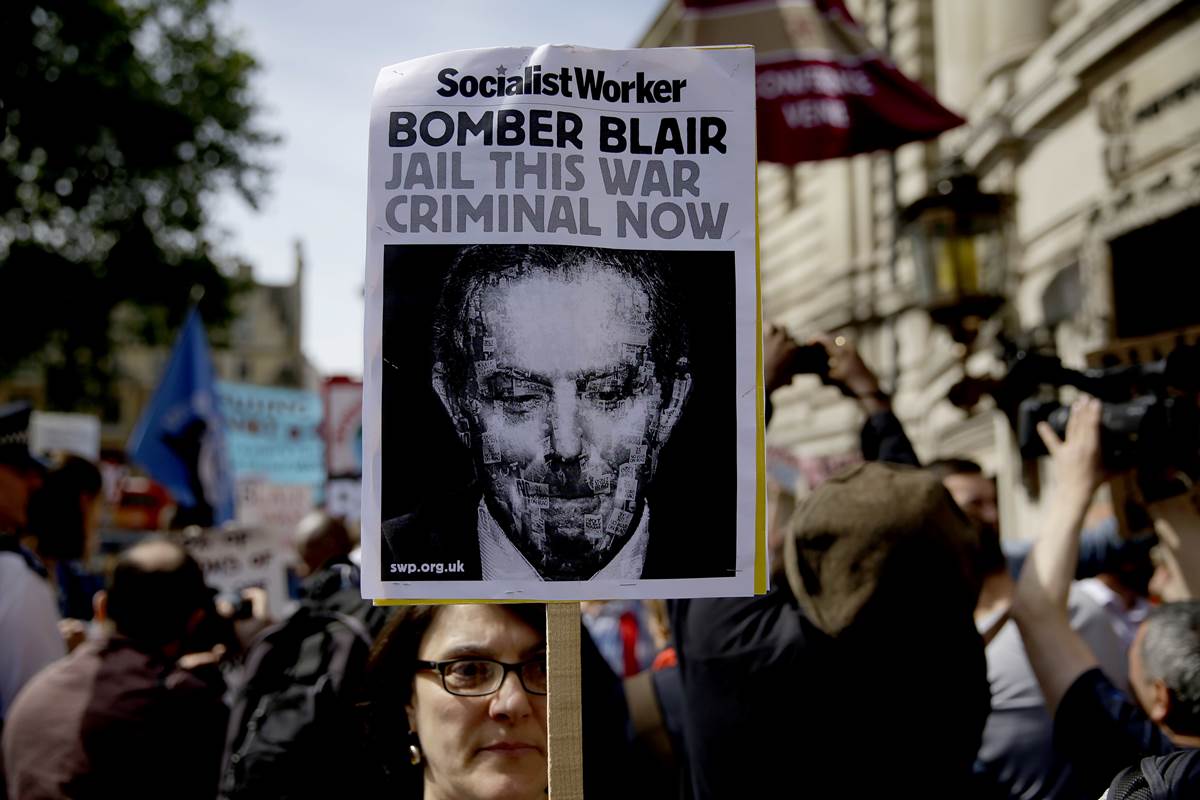

A protester holds up a placard during a demonstration outside the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre in London, before the publication of the Chilcot report into the Iraq war, Wednesday, July 6, 2016. The Iraq war was mounted on flawed intelligence, was executed with "wholly inadequate" planning, and ended "a long way from success," according to a damning report released Wednesday by the head of Britain's Iraq War inquiry. (AP Photo/Matt Dunham)

A protester holds up a placard during a demonstration outside the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre in London, before the publication of the Chilcot report into the Iraq war, Wednesday, July 6, 2016. The Iraq war was mounted on flawed intelligence, was executed with "wholly inadequate" planning, and ended "a long way from success," according to a damning report released Wednesday by the head of Britain's Iraq War inquiry. (AP Photo/Matt Dunham) For the last seven years, Sir John Chilcot worked at investigating the United Kingdom’s role in the Iraq war — one year longer than it took to fight the war, which claimed a staggering 5,00,000 lives, and unleashed a tide of blood that continues to sweep across the world today. His 2.6 million-word report is a magisterial account of what went wrong. “The UK chose to join the invasion of Iraq before the peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted,” it states. “Military action at that time was not a last resort.” The September 2002 dossier published by Prime Minister Tony Blair’s government, claiming Iraq held weapons of mass destruction, he goes on, presented judgments “with a certainty that was not justified”. “It is now clear that policy on Iraq was made on the basis of flawed intelligence and assessments”, he goes on. “They were not challenged and they should have been”. That is a failure Chilcot sets right in a manner that ought to be a model for democracies everywhere.

The full wrath of Chilcot’s criticism falls on Blair himself, but also on the system of institutions that ought to have contained the PM’s hubris. Sir John Scarlett, the head of the joint intelligence committee, “should have made clear to Mr Blair that the assessed intelligence had not established ‘beyond doubt’ either that Iraq had continued to produce chemical and biological weapons or that efforts to develop nuclear weapons continued.” In addition, MI16, failed to ensure that ministers were “informed in a timely way when doubts arose about key sources and when, subsequently, [that] intelligence was withdrawn”. Chilcot declines to express a view on whether the war had a sound legal basis, saying this can be determined only by an international criminal court with the necessary jurisdiction. He states, “the circumstances in which it was decided there was a legal basis for UK military action were far from satisfactory”.

Britain was at best a bit actor in the Iraq tragedy — but like the US, it had no coherent plan to rebuild the nation it was about to destroy. Indeed, the “scale of the UK effort in post-conflict Iraq never matched the scale of the challenge”. Things deteriorated further, the report notes, when the UK began simultaneous operations in Afghanistan. In 2007, British forces in Basra in essence handed over the region to local militia, in return for an end to attacks on themselves. The British military enterprise, Chilcot says, ended “a very long way from success”. “If you break it, you own it”, Colin Powell, the former US Secretary of State, once warned regime-change enthusiasts. Tragically, no-one owns today’s broken Iraq — nor owes its people justice.