Opinion Who’s my neighbour: For us, Adivasis, the neighbour is family

However, in recent times, in tribal villages, religion seems to be breaking down age-old bonds. Communication appears to be breaking down among people who stayed together in good and bad times

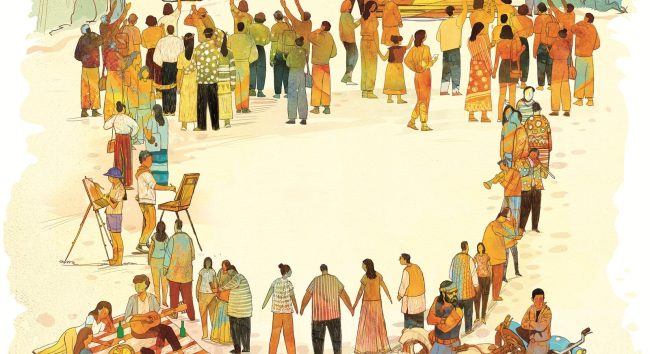

A family gave me a room on rent. It struck me that the women of the house never saw me as a tenant. (Credit: Suvajit Dey)

A family gave me a room on rent. It struck me that the women of the house never saw me as a tenant. (Credit: Suvajit Dey) Written by Jacinta Kerketta

Taking admission in a graduate course in St Xavier’s College in Jharkhand’s capital, Ranchi, posed challenges for someone who had, till then, lived all her life in a rural part of the state. In those days, only two buses would run from the Manoharpur block of West Singhbhum district to Ranchi. A more reliable option was to catch a train from a small railway station, about seven km from the village. To reach there, one had to first walk to a road, about three to four km away, and then wait for an auto rickshaw. There were fewer autos then compared to today. That meant one had to leave home early to have time in hand to catch both the rickshaw and the train. This train would take us to Rourkela in Odisha. There, one had to change trains to reach Ranchi. Most of us had very little money. That often meant travelling without a ticket. One had to be alert to the ticket checker’s presence and, at times, even get down before the station and walk along the tracks to reach the destination.

It was very early, the day I caught the train. Perhaps that’s why I was lucky and no ticket checker came to the coach. Somehow, I reached Ranchi. Though I filled up the form before I even reached the city, upon arrival, I came to know that the selected students would have to give a test in a few days. But where would I stay in the city till then? I had made up my mind to go to the railway platform and sleep there. I was making my way towards Ranchi railway station when someone put a hand on my shoulder. I turned around with a bit of trepidation. A girl had come running towards me and was huffing and puffing. In between her panting, she said, “Once you and your mother had visited the village next to yours. People of our village know your grandmother.” I recalled that once my mother had taken me to a village on the other side of the river. The girl who tapped me on my shoulder was from a family in Ranchi whose visit to my neighbouring village coincided with that of ours. I did not know her name, but I could recall her face. She invited me to stay at her house and gave me a room. I stayed with her for a few days and took my college entrance test. When I was going back home, she quietly put some money in my hand. It was a deeply moving gesture.

I stayed in Chainpur, a small village in Gumla district on the Jharkhand-Chhattisgarh border, for three years. A family gave me a room on rent. It struck me that the women of the house never saw me as a tenant. Every evening, we would drink tea together. At times, we also ate together. In winters, we would light a fire and chat beside its warmth, often till late at night. They would share the vegetables from their garden, and I was never short of fruits like mango, banana, and papaya. Once, there was no electricity in the village for several days. The water tank in the house went dry. My host would manage by storing water in utensils she would fill up from the tap. One day, when I returned home after a particularly tiring journey, I saw that she had got water filled for me too. My neighbour considered me a part of her family.

The memories of the two incidents remind me of a distinct trait of tribal societies — a neighbour is not just a neighbour, she is also a part of the family. Everyone is a part of a big family — inheritors of the same universe, who share the same vast consciousness. They are descendants of the same ancestors. Tribal society has a tradition to consider neighbours as family. The gotra system followed by tribal communities is another reason for such bonds of amity. People of the same gotra, no matter where they are in the world, are seen as relatives. People of other gotras are also seen as kin.

In many tribal villages, people of different castes and different professions, often from far-off places, are given land — neighbourly ties develop. In these communities, rituals like phool jodana and sahiya jodana help nurture kinship ties, even among people who might be from a different caste, or among those who speak a different language and have a different lifestyle. These rituals affirm that people will stand by each other in moments of happiness and sorrow.

However, in recent times, in tribal villages, religion seems to be breaking down age-old bonds. Communication appears to be breaking down among people who stayed together in good and bad times. The significance of the rituals, too, has declined. Hearteningly, some tribals, like my friend and neighbours whose stories I recollected, continue to retain the warmth of the past. Even today, there are many tribal areas where a neighbour is seen as a part of the family.

The writer is an Adivasi poet and writer