Opinion Roald Dahl controversy: What well-meaning adults still don’t get about children

They underestimate their resilience. Instead of proselytising young readers, adults could try explaining how context works in literature and leave children to take away what they will from Dahl’s irreverent and ridiculously fun work

Undertaken by Puffin Books and the Roald Dahl Story Company, the project involves the purging of much of what made the Dahl books irreverent and ridiculously fun.

Undertaken by Puffin Books and the Roald Dahl Story Company, the project involves the purging of much of what made the Dahl books irreverent and ridiculously fun. In 1990, the year he passed away, in an interview with The Independent that is remembered primarily for the reiteration of his shocking anti-Semitic views, British writer Roald Dahl also revealed his winning formula for children’s books — to show up the absurdity of adults from a child’s perspective by making larger-than-life caricatures of them. “It may be simplistic, but it is the way…The adult is the enemy of the child because of the awful process of civilising this thing that when it is born is an animal with no manners, no moral sense at all,” Dahl reportedly said in the interview, quoted by The New York Times in their obituary of the writer in November that year.

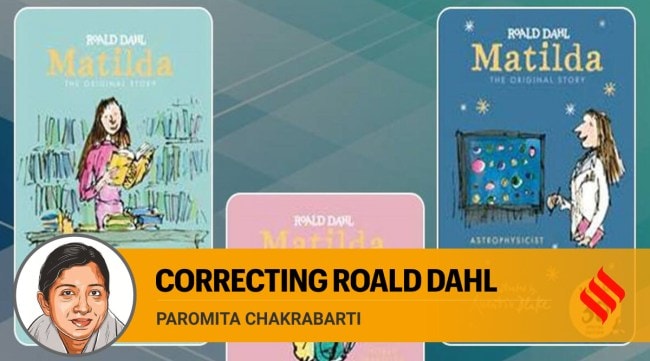

Over the course of his long and wildly successful career, Dahl let rip all the ways that an adult can be a figure of ridicule and surreptitious pity for their failure to really “get” children. Now, a little over three decades after his death, a report by The Daily Telegraph has thrown light on how a new civilising project is underfoot. Undertaken by Puffin Books, the children’s book imprint of Penguin Random House, and the Roald Dahl Story Company, his estate, it involves the purging of much of what made the Dahl books — from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964) to George’s Marvellous Medicine (1981), from The BFG (1982) to Matilda (1988) — irreverent and ridiculously fun. In collaboration with an organisation that works towards inclusivity, and in a purported bid to ensure that “Dahl’s wonderful stories and characters continue to be enjoyed by all children today”, the report details how “language relating to weight, mental health, violence, gender and race” among others, are being sanitised according to contemporary sensibility. “Fat”, “ugly” and “crazy” are off the table, even if they appear in books written before the usage of such descriptors became retrograde; the imagination of a “real witch” being “bald” is to appear with explanations of all the other reasons a woman can lose hair; “mothers and fathers” and “ladies and gentlemen” are gender-neutral “parents” and “folks” respectively. And these are only a few of the hundreds of proposed changes in new editions.

There has been a great deal of outrage over the amendments, including from writers such as Salman Rushdie, who sees it as an attack on free speech, and Philip Pullman, who argues for its right to fade into oblivion. Even British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has voiced his objection to the enterprise, and rightly so.

We live in an age of great cultural fragility, where egos bruise easily and self-esteem gets fractured at the slightest imagination of hurt, where writers can be hounded to announce the demise of their creative selves on social media or harassed relentlessly for their views on contentious issues. One has only to look at the examples of Perumal Murugan at home or the repeated calls for “cancelling” JK Rowling over her complicated views on trans rights to realise that virtue signalling can be obdurate when it comes to nuance. And when it trains its lens on the past, in its insistence on shepherding imaginations into a landscape of acceptable homogeneity, political correctness can be weaponised to create a narrow revisionist culture that defeats the very idea that lies at the core of literature — an acknowledgment of diversity that can comfort and rattle, shock and thrill.

One may well argue that the alternative to this is a reconciliation with what is quite obviously a problematic legacy. Like another hugely popular children’s writer before him — Enid Blyton — Dahl’s legacy is complicated by his anti-Semitism, misogyny, and the White man’s colonial baggage. In 2020, a year before its acquisition by Netflix (and perhaps, to stave off any potential backlash to several upcoming cinematic projects based on Dahl’s works), the Roald Dahl Story Company and the writer’s family put forward an apology for his prejudices and the hurt he caused. Whatever the reason, acknowledging Dahl’s shortcomings opened up a conversation on the fault lines that exist — as the UK-based charity English Heritage, which installs iconic blue plaques at sites that were once the working or living quarters of Britain’s culturati, did with its updating of information on Blyton’s plaque outside her home in south-west London in 2021, detailing instances of xenophobia and racism in her work.

Policymakers at various levels are often guilty of undermining context, but it’s a pity how little well-meaning adults understand the innate resilience of children. Instead of proselytising young readers with persistent overwriting, perhaps they could try giving them a note on how context works in literature and leave them to take away what they will from the fantastical and macabre imaginings of the writer. As someone whose books have sold over 300 million copies worldwide, it was one of the things that Dahl did get right and there is no need to tamper with that.

paromita.chakrabarti@expressindia.com