Opinion Reverting to Old Pension Scheme: A move at the expense of the poor

Shamika Ravi writes: It would result in a reallocation of resources from development expenditure that benefits the poor towards a smaller group of people who have benefitted from secured jobs

Shamika Ravi writes: Globally, with an ageing population and increased life expectancy, government employees’ pensions have become a major political issue. (File image/Express)

Shamika Ravi writes: Globally, with an ageing population and increased life expectancy, government employees’ pensions have become a major political issue. (File image/Express) One of the most far-sighted reforms in India was the pension reform implemented by the NDA government in 2003–04, called the New Pension Scheme (NPS). The key feature of the NPS was a move towards a broad-based and sustainable contributory pension system and away from the old pension scheme (OPS), where the government was obliged to pay pre-determined benefits to public employees post-retirement. Under the OPS, public employees did not contribute to their retirement. Over time, as public employees’ life expectancy increased, the state’s fiscal burden under the OPS began to rise exponentially, necessitating pension reforms. There was a paradoxical situation in India. While more than 80 per cent of the labour force works in the informal sector with practically no job security and old-age financial support, the 5-6 per cent of the workforce that worked for the government enjoyed job security and very generous post-retirement benefits.

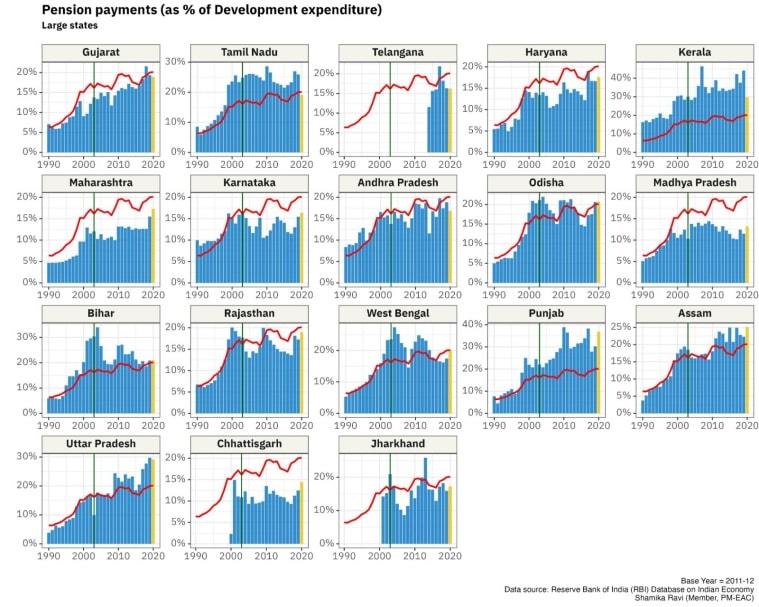

In recent times, however, while some state governments have already reversed the pension reform and returned to the financially burdensome and fiscally non-viable OPS, in other states, there is a growing political clamour to reinstate the OPS. In this essay, I wish to go beyond the OPS’s fiscal burden and financial viability and focus on the economic tradeoffs that the state governments would have to reckon with, particularly its impact on the poor and the vulnerable. Objective analysis of state budgets of 30 years from 1990 to 2020 highlights two points that merit consideration.

My first point relates to the tradeoff within the state budget between development and non-development expenditure. Development expenditure is primarily on (a) social services such as health, and education; and (b) economic services, which relate to rural and urban development and infrastructure. Non-development expenditure is primarily for administrative services, interest payments and debt servicing, and pensions.

Shamika Ravi writes: My first point relates to the tradeoff within the state budget between development and non-development expenditure.

Shamika Ravi writes: My first point relates to the tradeoff within the state budget between development and non-development expenditure.

A fundamental lesson from this analysis was the tradeoff between pension and development expenditure of the states. The pension reforms were hence a watershed moment for the states. Reversing to the OPS, would therefore, result in a reallocation of resources away from the state’s development expenditure which benefits the poor, and towards a much smaller group of people who have benefitted from a secured and privileged job throughout their working life. Given that economic services such as infrastructure and rural and urban development were affected more severely than social services, it would reduce the productivity of the poor, further diminishing their future economic prospects. In brief, going back to the OPS will worsen inequality and lower economic growth in the states.

The second tradeoff emerges from the financing of the state budgets. Two avenues were available to finance the increased non-development expenditure related to pensions. One way was to raise revenues primarily through taxes, and the other was to finance the deficits by borrowing. Our analysis revealed that from 1990 to 2004, the states’ revenues did not match the state’s increased expenditure. Therefore, the deficit of the state governments increased exponentially. To better understand this, we computed, for each state, the real per capita gross fiscal deficit (GFD) from the state budgets, allowing us to make comparisons over time and across states. The real value was computed by deflating the nominal values with the yearly price deflator for each state. Time series on state-level price deflators were calculated from RBI annual time series data on the Net State Domestic Product (NSDP) at factor cost in constant and current prices, with 2011–12 as the base year.

Shamika Ravi writes: The second tradeoff emerges from the financing of the state budgets

Shamika Ravi writes: The second tradeoff emerges from the financing of the state budgets

Analysis of the state budgets revealed that on a per-capita basis, the real GFD for all the states more than doubled from Rs 995 in 1990 to Rs 2,129 in 2003. In terms of the ratio of GFD to the NSDP, it worsened from 3.6 per cent in 1990 to 4.9 per cent in 2003. The GFD was financed primarily by borrowing from the markets, National Small Savings Fund (NSSF), and loans from the Centre. The fundamental tradeoff, therefore, was that increased state borrowing to finance non-development expenditure was effectively crowding out private investment. Resources that would otherwise have been available to the private sector for investment and fostering growth were now being spent for the consumption benefits of the few privileged retired public sector employees.

Globally, with an ageing population and increased life expectancy, government employees’ pensions have become a major political issue. For example, France is witnessing violent protests against government reforms attempting to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64. The Indian government, in 2003–04, had the political will and far-sightedness to introduce pension reforms to make the state budgets sustainable. The data clearly shows the structural break post the reforms. The real beneficiaries of the Indian pension reforms were the poor and vulnerable, including women and children; the state resources that went to them otherwise would have been crowded out by the privileged and the organised few. The analysis suggests that state governments, over and above the financial feasibility of the OPS, would need to think hard about its impact on the poor and vulnerable, particularly women and children. In states like Himachal Pradesh and Punjab, pensions as percentage of development spending already account for a whopping 37 per cent and 31 per cent and are among the highest anywhere. So, for these states, the reversal to OPS will certainly have a catastrophic impact on their poor populations. The reversal will deprive the poor of essential services such as health and education. It also prevents them from participating in growth opportunities when resources are reallocated from the infrastructure needs of the poor to the excessive consumption of the privileged few.

The writer is Member, Economic Advisory Council to Prime Minister of India