Opinion 20 years of the Delhi Metro: How the metro defines who has the right to mobility in the city

Rashmi Sadana writes: People across classes enter a new social contract on the metro. It not only creates a new form of mobility through urban space and over time, but also across a large swathe of the working and middle class of the city

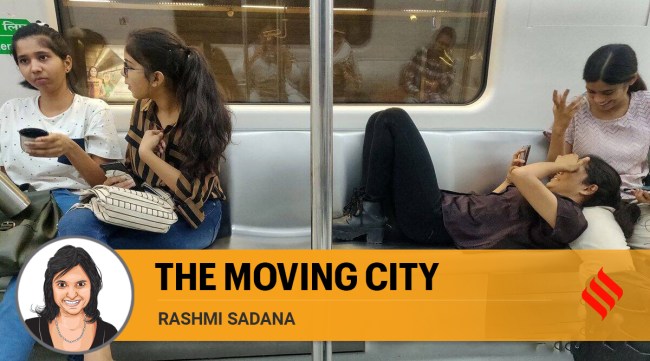

The metro has also brought a new kind of visibility in the city. What happens on the metro, moments of connection and reconciliation but also disregard or even violence, takes on new significance. (Express File Photo)

The metro has also brought a new kind of visibility in the city. What happens on the metro, moments of connection and reconciliation but also disregard or even violence, takes on new significance. (Express File Photo) When I started to do research about the Delhi Metro in 2008 for my book, Metronama, I initially thought of the metro — its trains, stations, and viaducts — as new kinds of objects in the city. I was struck by their materiality — the way a station entrance seemed to pop out onto the urban landscape, or the feel of being on an escalator as it descended into the depths of the city. We could touch the shiny surfaces and move across the lighted platforms. The system was automated and air-conditioned. It was a relief.

The metro has brought a new set of textures into the city and into our daily lives. It is a system that takes you places, but it has also become a new place to be. There was nothing to compare it to in Delhi before. On the metro, crowds took a different form; they were not merely a sign of excess. The metro was meant to be crowded. It was built to be crowded. Metro crowds have a purpose and order, but they also represent a new kind of mobility in the city. In the ladies’ coach, I revel in the crowd — all these women going places, to work, to see friends or family, to meet someone, to pick something up, to have an adventure or a new experience. The metro became a place to people-watch and to understand new aspects of the city, especially its new pulses and surprising vistas. In the general coaches, women and men were largely fine sitting and standing amongst one another. The open coach design encourages fluidity — gendered and otherwise.

People across classes enter a new social contract on the metro. It not only creates a new form of mobility through urban space and over time, but also across a large swathe of the working and middle class of the city. Even 20 years on, the metro is not going to create social equality, but it provides some alternatives to being stuck. I think of these alternatives as “metro mobility.” This movement represents just a slice — about 5 per cent of trips in the city — but gives a sense of the possibility of a truly moving city. This idea of a moving city represents how my research shifted by the time phase three was being built. I no longer saw the metro as merely an object to study, but rather as a circulation in which to be moved along. The city was expanding before our very eyes and in our bodily movements through urban space, as we sensed the expansion each time we took the metro to Noida or Gurgaon or Mundka. “Delhi” was being remade with the addition of each station and line. The metro was becoming more than an object; it was an experience of metro mobility.

Mobility is about movement, but it is also about social change. Who gets to be mobile and who doesn’t is a question of power. Mobility is key to one’s right to the city. This is also why Delhi’s metro is unique in India. For a metro to have a real impact, to create metro mobility, you need many lines and stations. It is the reach of the metro that is transformative, the way it can cut a one-hour journey to 20 minutes, but also create new spatial imaginary where Badarpur can be connected to Majlis Park or Seelampur to Huda City Center. This reach creates new opportunities for people, as well as a new experience of time. This is true for people living in Delhi, but also for those who come from further afield, from Meerut or Rohtak, for instance. “Delhi” starts at the ends of the lines where “hinterlands” become hubs.

The metro has also brought a new kind of visibility in the city. What happens on the metro, moments of connection and reconciliation but also disregard or even violence, takes on new significance. It is noticed more because it happened on the metro. It has become a social stage in the city. The metro represents modernity and progress and everything that happens there is set against those ideals. The tragic suicide attempts nearly each week are part of that disturbing drama. Ideals and reality do not always match up the way we think they should. Instead, they become fault lines requiring new forms of understanding and action.

Nevertheless, because it is affordable for many (not all), safe, and well-lit (basic requirements for good public transportation), the metro widens the imagination of what is possible in life. It makes the city more visible, but it also creates a new relationship with the self. And in the end, this is where my research led me: To the people who ride the metro and the stories therein. And this is what I also think is most significant about the metro on its 20th anniversary: How people create and experience their own itineraries in and through the city and in their own lives.

I ultimately came to see the metro as a series of scenes — a kind of moving tableaux. Taken together the scenes represent individualised, anonymous travel, and yet, this travel is done together, side by side. Metro mobility is a new sort of collective experience that holds the promise of new kinds of collectivities. The metro’s greatest impact is in how we see each other anew. At its best, the metro expands who should be included in the idea of “the public” and who has a right to mobility in the city. There is no going back now, but there also must be some deliberation as we go forward. Growth alone should not be the aim of the metro, but rather building new and more stable connections across different types of public transport to extend metro mobility, in all its forms, to more people.

Sadana teaches at George Mason University and is the author of Metronama: Scenes from the Delhi Metro (published in the US as The Moving City)