Opinion Bihar electoral roll revision is an exercise in exclusion

The people of Bihar are no strangers to struggle, and this latest battle must be fought not just at the doors of the court but at the doorsteps of every citizen

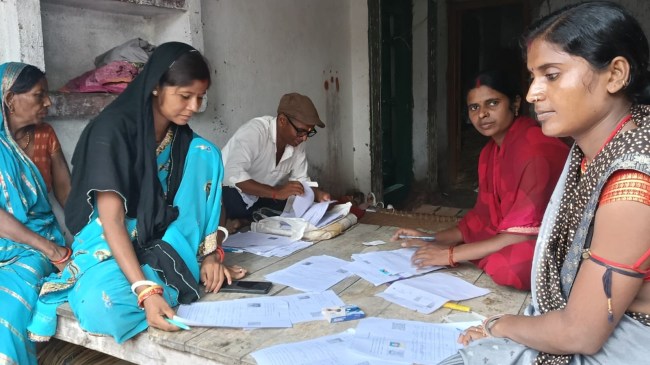

During the Special Intensive Revision of electoral rolls in Bihar’s Nawada district on Sunday. (Image source: X/@CEOBihar)

During the Special Intensive Revision of electoral rolls in Bihar’s Nawada district on Sunday. (Image source: X/@CEOBihar) The Election Commission of India (ECI) has launched a sweeping Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar. Though presented as a legitimate administrative effort to update voter data ahead of the Assembly elections, the move has drawn criticism and legal challenges. The ECI has initiated door-to-door verification of voter records across the state, demanding submission of multiple documents including personal and parental proof of age and residence, particularly for those born after 2003. While the stated purpose is to remove inaccuracies and eliminate ineligible voters, the exercise stands out for its timing and the implications for already vulnerable populations.

Bihar has one of the highest concentrations of working people and marginalised communities in the country, many of whom are under-documented and live in conditions that make it impossible to maintain consistent paper trails. For migrant workers, Dalits, Adivasis and the rural poor, furnishing documents that prove not just their own eligibility but that of their parents within a month’s notice is an almost insurmountable challenge. These groups now face the prospect of disenfranchisement, not due to fraud or manipulation but due to systemic inequality and administrative insensitivity. The scale and pace of this process, during the monsoon season and across difficult terrain, virtually guarantees errors and exclusions. This fear was echoed in the Supreme Court when a judge observed that even someone of his stature would struggle to produce the kind of documentation now being demanded.

This observation from the judiciary came during the ongoing hearings on the constitutional validity and timing of the SIR. The author of this article is also a petitioner before the Supreme Court, part of a collective legal challenge to the SIR by 10 Opposition parties. The Court has taken note of our apprehensions and has asked pointed questions to the ECI, including on the timing of the exercise. Further, the Court has also asked the ECI to consider other documents like Aadhaar cards, ration cards and the EPIC, which is issued by the ECI itself, for the SIR. The very fact that the judiciary had to intervene in an exercise that should have been routine and inclusive is a troubling sign.

What makes this exercise even more suspect is its political context. The BJP, which has ruled at the Centre for over a decade and has all but eclipsed other parties in Bihar’s ruling alliance, has continuously devised new methods to retain power in politically crucial states like Bihar. Whether through orchestrated defections, covert encouragement of splinter groups, or manipulation of alliances, the BJP has shown an unwillingness to respect electoral uncertainty. With its position weakening in Bihar and the Opposition Mahagathbandhan gaining strength, the SIR appears to be the newest instrument in this playbook. The demand for complex documentation will disproportionately affect voters who are less likely to support the BJP, the poor, Dalits, minorities and migrant workers. What is being portrayed as a neutral administrative measure is, in fact, deeply political.

While the ECI has defended the process as constitutionally mandated and necessary under the Representation of the People Act, these claims do not hold up to scrutiny. No such intensive revision was undertaken in other states that recently went to the polls. The electoral rolls in Bihar had already been updated for the 2024 Lok Sabha elections. A limited update to include new eligible voters would have sufficed. The ECI is yet to offer a clear explanation for the surge in the number of voters before the Maharashtra elections. This selective use of revisions raises questions about whether these exercises are being conducted impartially. Most tellingly, BJP spokespersons have been far more enthusiastic in defending the SIR than the ECI itself. This creates the impression that the ECI, while formally neutral, is presiding over an exercise whose political consequences are highly skewed.

This perception has been strengthened by recent changes in the appointment process of Election Commissioners. The Union government now holds the sole authority to appoint the Chief Election Commissioner and other Commissioners, a move that weakens the structural independence of the institution. In public forums and press interactions, the ECI has failed to assert its autonomy with the kind of firmness shown in the past. It is worth recalling that former Chief Election Commissioner T N Seshan deliberately stopped using the term “Government of India” in Commission communication to underline its institutional independence from the Executive. Today, such symbolic and substantive measures are largely absent, and public confidence in the Commission’s impartiality is eroding as a result.

The timing of the Bihar revision is particularly telling. With only months to go before the announcement of elections, lakhs of voters are now scrambling to confirm their inclusion on the rolls. Many face uncertainty, confusion and fear. In a democracy, no citizen should be in doubt about their right to vote. Yet in Bihar today, this doubt has been manufactured, not resolved, by the very institution meant to protect electoral rights. The revision has come as a shock to voters who had already voted in the 2024 general elections and are being asked to once again prove their eligibility. The burden of proof has unfairly shifted to the citizen, and the consequences will likely be felt most by those already marginalised by the system.

The right to vote for an eligible citizen is not a privilege that should be filtered through bureaucratic red tape. It is a right and any attempt to limit it under the pretext of administrative reform must be challenged firmly and decisively. The people of Bihar are no strangers to struggle, and this latest battle must be fought not just at the doors of the Court but at the doorsteps of every citizen.

The writer is general secretary, CPI