The seven year hitch

Houseboats in Srinagar give pride of place to leather-bound visitors8217; books to record outpourings of impressed guests. The houseboat in...

Houseboats in Srinagar give pride of place to leather-bound visitors8217; books to record outpourings of impressed guests. The houseboat in which I stayed a few days ago had two entries that struck me, not for the name of the guests but for the time gap between them. The first one was in 1989 and the second in 1996. The seven-year period tells you all about Kashmir. This was the time when the insurgency in the Valley was at its height. From 1996 the graph began to dip. By then what was initially an uprising to break away from India had deteriorated into Pakistan-aided militancy with a large number of foreigners participating.

Why did Islamabad fail to get any response to the infiltration it sponsored in 1965 and why did the same Kashmiris pick up arms 24 years later 8212; on these questions hangs the seven-year-long history. Till 1987, when assembly elections were held, Kashmiris were confident that they had the power to vote out rulers who failed them. But when they found that they could not do so because of electoral rigging, hundreds of them crossed into Pakistan, which was only too willing to provide training and weapons.

In Srinagar, in January 1990, the late Abdul Ghani Lone confirmed that hundreds of boys had gone across the border to get weapons. Islamabad, he told me, had been vainly wooing them for a long time. Loss of faith in the ballot forced them to rely on bullets which they got from across the border.

Has violence helped? This was the question I raised at Kashmir University where its Mass Communication Department and the Press Institute of India had organised an interactive session with students. I told them that if the movement, which some leading Kashmiris blessed, had been non-violent, it would have made a lasting impression on civil society in India. Many of the students did not agree with me. They said they had no option except to wield the gun, because they had not won anything through peace.

This is not true. The insurgency raged for seven-eight years. It had to be suppressed forcibly, at times through questionable methods. It gave a bad name to the Kashmiris. Part of the frustration they face in not getting admission to universities outside the state is because of the violence which haunted the Valley. The same reason can be offered for fewer employment opportunities in the rest of the country. A Kashmiri has come to be associated with the gun.

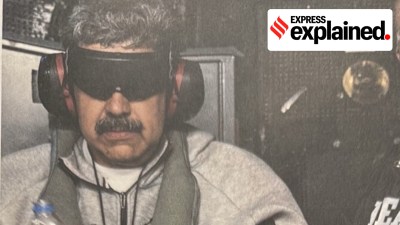

I recall how persuasion by some human rights activists changed Yasin Malik, the first militant. He is now a Gandhian and has even turned vegetarian. He admits that a non-violent movement would have had far more impact than the violent one they conducted, losing in the process more than 35,000 young Kashmiris. The hotheaded students should realise that the state is powerful enough to withstand the insurgency 8212; and it has proved that.

Now that the feel-good factor is returning, there is a need to consolidate it. I visited the Valley after three years. Srinagar is now an overcrowded city where traffic jams are a routine occurrence. The presence of the security forces is far less visible than it was before. Bunkers with guns jutting out have been either demolished or covered with a piece of blue cloth. Women are seen walking on the streets even after ten at night in all parts of the city. A burqa-clad woman is a rare sight.

One odd thing I found this time was that no one talked about Jammu or Ladakh 8212; as if Hindu and Muslim fundamentalists had already succeeded in their propaganda. Kashmiri pandits were mentioned and there was a strong feeling in certain quarters that they must return to their homes because they have been an integral part of Kashmiri society for centuries.

The healing touch which Chief Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed underlines all the time has evoked hope. Interrogation centres have been closed down and there is some action when excesses by the security forces are reported. Young men still disappear but in far lower numbers than before. As many as 1,500 young men are still to be accounted for. Custodial deaths are, however, still taking place and in certain cases the chief minister is reportedly as angry and helpless as the average person. I was informed that the number of detenus is very small.

What has impressed the common man is the influx of tourists, nearly 1.5 lakh. Once again hoteliers, houseboat-wallahs, taxi drivers and shikara pliers are counting their earnings at the end of the day. They had practically nothing in recent years. People are beginning to reaslise that they have a vested interest in peace because they want more and more tourists to come. There were some 10 lakh of them when the first entry, that of 1988, was made in the houseboat8217;s visitors8217; book.

Still, the militants, who are lying low, can rupture this atmosphere. Probably they are afraid of facing the wrath of the locals who are sick and tired of violence. I am sure that the students who talk about the gun realise the troubles any spurt in violence would bring in its wake. But New Delhi would be fooling itself if it believes that the security forces or the Mufti government8217;s less harsh policy has solved the Kashmir problem. It has to be tackled right now. This is the impression with which I have returned from Pakistan as well.

Not many who count are spelling out any solution. But they are waiting for a further initiative by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee who has transformed the atmospherics by saying that he wants a dialogue with Pakistan. True, his condition is that cross-border terrorism must cease first. He would be surprised how easy it would be to silence the guns if he were to talk to all parties in Kashmir. And that includes the Hurriyat which has crowded out the fundamentalists in its midst. That the Mufti government is trying to woo them is an unfortunate development.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05