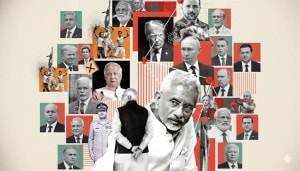

Lal Badshah

IN the telegrammatic world of newspaper headline writers, a chestnut that resurfaces periodically, especially in the murky, confusing season...

IN the telegrammatic world of newspaper headline writers, a chestnut that resurfaces periodically, especially in the murky, confusing seasons before and after an election, when coalitions are simultaneously evaporating and solidifying is 8216;8216;Surjeet active again8217;8217;. The story never changes 8212; it involves the CPIM general rushing from one Lutyens8217; Delhi bungalow to another, flying from one state capital to another, meeting one regional politico after another, all in search of that political pot of nectar 8212; opposition unity. So it was this past week, so it was 20 years ago. Then the enemy was the Congress, now it8217;s the BJP.

Just under 88, Harkishen Singh Surjeet is blessed with prodigious energy. He is a man who wears many turbans 8212; a consummate deal-maker who combines Punjabi enterprise with Marxist doggedness, worldwide travel with outdated worldview, marginal political party with disproportionate personal influence. Perhaps his finest hour 8212; certainly his busiest 8212; was the comic drama called the United Front government, 1996-97.

First, Surjeet and Jyoti Basu sought to persuade the CPIM to allow Basu to become prime minister. When the party refused 8212; it didn8217;t want to lend a leader to a government it couldn8217;t control 8212; a disappointed Surjeet settled for second best. As accidental prime minister H.D. Deve Gowda8217;s chief adviser and all-purpose guardian in the capital, he became, arguably, the most powerful communist in Indian history.

In his dream world 8212; and every Marxist8217;s world is full of dreams, even if most of them turn out to be delusions 8212; he8217;d be performing the role for Sonia Gandhi later this year, after the Lok Sabha election.

Surjeet is convinced the Congress has to be the centrepiece of a 8216;8216;secular alliance8217;8217;. He also recognises that parties such as his own CPIM in Kerala and West Bengal and the Samajwadi Party in Uttar Pradesh see the Congress as a local rival. So he has proposed the theory of two coalitions 8212; one under the Congress, the other comprising the Congress8217; regional rivals, which are also the BJP8217;s national rivals.

The two coalitions will fight the election separately, with unpublicised tactical arrangements, and then miraculously combine post-poll to form a non-BJP government. By then, hopefully, chacha Surjeet would have worked on the Telugu Desam and half the NDA as well. So fantastic is the two-coalition formula, some in Delhi are already labelling it 8216;8216;dialectical immaterialism8217;8217;.

A particularly heightened imagination has long been a feature of Surjeet8217;s politics. In the 1970s, he decided the Akalis were 8216;8216;progressives8217;8217;, somehow fellow travellers. To this day, he dreams of an India-China-Russia axis to take on big bad Uncle Sam.

Yet some would say he has his heart in the right place. In the 1980s, Punjab8217;s terrible decade of terrorism, Surjeet and the CPIM spoke out bluntly against the idea of Khalistan, many cadre paying for it with their lives. Surjeet is also extremely well-networked 8212; his friends range from the Sikh diaspora in Canada to the socialist dinosaurs in Cuba, from Amar Singh to V.P. Singh. Along with Jyoti Basu, he is the last of the team that founded the CPIM in 1964.

He8217;s also perhaps one of the last links with the socialist fervour of the Punjab of the 1930s. A member of the Naujawan Bharat Sabha, founded by Bhagat Singh, Surjeet8217;s early years were hard. His father, an army veteran, joined the national movement after World War I, becoming an Akali and going to prison. Surjeet himself was arrested at 16. That was on March 23, 1932, the first anniversary of Bhagat Singh8217;s martyrdom 8212; and coincidentally Surjeet8217;s birthday. The intrepid young lad took down the Union Jack and hoisted the tricolour at the Hoshiarpur didstrict court. When arrested, he told the court his name was 8216;8216;London Tod Singh8217;8217; One who breaks London8217;8217;.

Always had a sense of theatre, didn8217;t he!

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05