📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

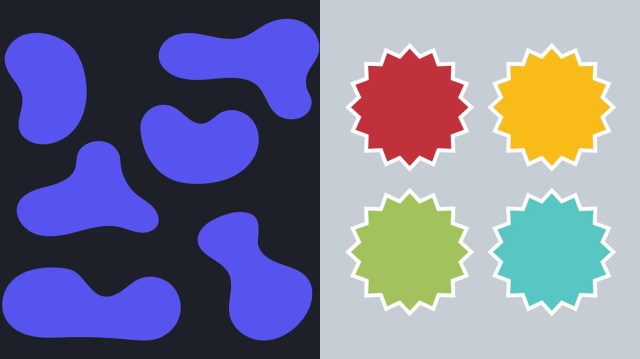

Try identifying which shape is ‘bouba’ and ‘kiki’ by looking at the picture (answer inside)

What does this phenomenon reveal about the way humans process information?

What is the bouba-kiki effect? (Source: Freepik)

What is the bouba-kiki effect? (Source: Freepik)Have you ever wondered why certain shapes seem to pair naturally with specific sounds? This intuitive association is at the heart of ‘the bouba-kiki effect,’ a psychological phenomenon that suggests humans have an innate tendency to link round shapes with softer sounds like “bouba” and angular shapes with sharper sounds like “kiki.”

First documented in the 1920s and later explored in modern studies, this effect challenges the traditional idea that language and sounds are entirely arbitrary. What’s particularly fascinating is how this effect appears to be universal across cultures, languages, and even age groups, hinting at a deeper cognitive connection between sound and visual perception.

View this post on Instagram

But what does this phenomenon reveal about the way humans process information, and how could it influence professional areas?

Dr Arun Kumar, consultant psychiatrist at Cadabams Hospitals, tells indianexpress.com, “The bouba-kiki effect highlights how our senses — specifically vision and hearing — interact to form coherent interpretations of the world. The soft, rounded phonemes in ‘bouba’ align with the visual perception of curves, while the sharp consonants in ‘kiki’ resonate with angular shapes.”

He adds, “This effect suggests that language is not arbitrary but rooted in sensory experiences. The way we produce sounds involves physical sensations (e.g., rounded lips for ‘bouba’) that align with visual patterns, shaping our perception.”

According to research published in Psychological Science, Dr Kumar states, this phenomenon may explain how humans develop abstract linguistic symbols. Early humans likely relied on such sensory associations to assign meaning to words, which evolved into structured languages.

How universal is this phenomenon?

The bouba-kiki effect is largely universal, transcending linguistic and cultural boundaries. “Studies conducted across diverse populations have consistently shown that most individuals intuitively associate “bouba” with rounded shapes and “kiki” with angular shapes,” notes Dr Kumar.

According to him, “Research published in PNAS found that speakers of languages as diverse as Tamil, English, and Himba (a Namibian language) exhibit similar sound-shape associations. The effect has been observed in young children, indicating that this association is intuitive rather than learned. Even infants as young as four months display a preference for congruent sound-shape pairings, as shown in studies in Developmental Science.”

Cultures with strong symbolic traditions, such as specific shapes linked to sacred sounds, might show deviations in their responses to the bouba-kiki test. (Source: Freepik)

Cultures with strong symbolic traditions, such as specific shapes linked to sacred sounds, might show deviations in their responses to the bouba-kiki test. (Source: Freepik)

Cultural and linguistic influences

While the effect is robust, Dr Kumar highlights the slight variations that can arise due to cultural or linguistic differences:

Language Phonetics: Languages with unique sound inventories may shape subtle biases. For instance, a language without sharp consonants may influence its speakers’ associations with angular shapes.

Symbolism and Context: Cultures with strong symbolic traditions, such as specific shapes linked to sacred sounds, might show deviations in their responses to the bouba-kiki test.

“Despite these nuances, the overwhelming consistency across cultures suggests the bouba-kiki effect is deeply rooted in universal cognitive processes,” he remarks.

📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05