Playing it Slow and Easy

Susmit Sen’s memoir traces his journey with the band Indian Ocean, but says little about his musical inspirations.

By Sidharth Bhatia

The rock revolution, to coin a phrase, faded out by 1980 and then began again with full force in the 1990s.

The rock revolution, to coin a phrase, faded out by 1980 and then began again with full force in the 1990s.

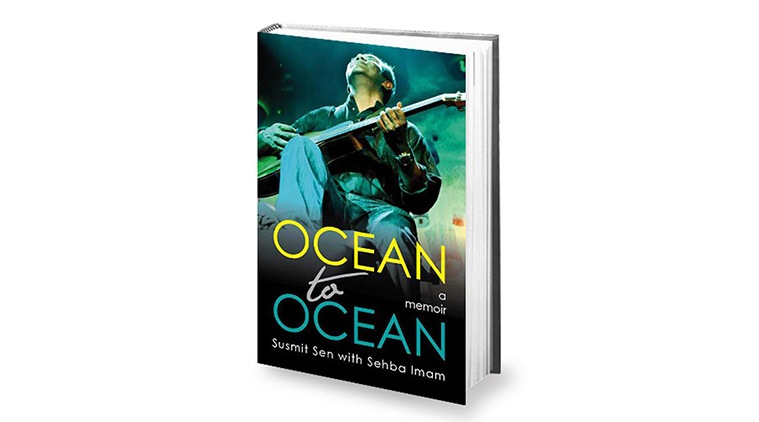

Book: Ocean to Ocean

Authors: Susmit Sen with Sehba Imam

Publishers: Harper Collins

Pages: 160

Price: Rs 699

In October 1962, when the Beatles released their first single, Love Me Do, it created a ripple of excitement around the world. The single only reached number 17 in the UK, but its impact was far-reaching. Around the world, youngsters heard this new sound and immediately took to it. Six months later, when the first LP of the group, Please Please Me was launched, it immediately shot up the charts. The Beatles had arrived.

In faraway India, where the local radio station did not play western music, young teens too fell in love with this music — within months, groups were popping up all over the country, in Bangalore, Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. Scores, if not hundreds of bands emerged on college campuses and elsewhere over the next decade-and-a-half, playing covers and original music on ratty guitars, wilting drum sets and amps and other equipment no self-respecting musician would touch. Besides, no one was ready to give a recording contract or pay big bucks to a non-Bollywood performer.

The rock revolution, to coin a phrase, faded out by 1980 and then began again with full force in the 1990s. Indian Ocean, Euphoria, Parikrama — the list is long. These groups had access to slightly better equipment and instruments, but they were very different from their predecessors — they wanted to create their own, entirely new sound and were ready to experiment with local languages. Other bands in the past had tried raga rock (Human Bondage) and Indian language lyrics (Mohiner Ghoraguli), but they were exceptions — most stuck to classic rock in English.

But, as Susmit Sen tells us in his memoirs, the journey to success in the 1990s was full of the same problems that his musical forebearers had faced. Recording companies remained sceptical, venues were few and far between, and as for money, you would be foolish to give up your day job.

Yet, Sen weaves a charming story of growing up, early struggle, later success and the joys and problems it brought. It has moments of gentle humour, reflection, self-deprecation and some candidness too. The book, as told to Sehba Imam, sounds and reads like a casual chat over a drink or three, the fire crackling, the mood nostalgic. There are no sudden flashes of drama or excitement, but a slow unfolding of a person’s journey.

The early chapters are about Sen’s childhood, a fairly middle-class one in Delhi, where he grew up with a father working for the government and two siblings. He had trouble with academics, barely getting through and then doing poorly in college — he explains it as his difficulty in fitting into a mould, something that plays out in later life, as he moves from job to job. But it also emboldened him to cross musical frontiers.

Sadly, though, Sen does not delve deep into the creation of his particular brand of music, which draws from the folk tradition, from Rajasthani to Baul. It’s called fusion rock, though this f-word again finds no mention in the book. Indeed, apart from talking about how he writes music that he can feel, rather than with any technical prowess, there is just no exposition of where his musical inspiration and sources lie. The combination of tabla and folkish warbling with guitar riffs has worked well in Indian Ocean’s case — often enough in the past it has gone horribly wrong — but why is that so? Sen would have done well to tell us.

The slow road to success is well described and when it came, with tens of thousands of sales from the very first album, it was a vindication of a tough decision to quit a steady job to concentrate full time on music. Yet, while gigs came by steadily, the big companies remained sceptical, till the next album too was a hit and then offers started pouring in. Indian Ocean were a fixture on the college festival circuit and then at festivals abroad.

After Asheem Chakravarty (tabla and vocals) died in 2009, the band continued, but it is obvious that for Sen the disillusionment set in. He papers over the details of the differences within the band, preferring to talk in esoteric, general terms (“It was when we were working on Jhini that I felt the first tinges of creative dissatisfaction. The synergy we used to have as a band seemed to be missing…) but it couldn’t have been that simple.

Fans of the band, who may know a lot about it, will still enjoy reading the slim book written in his own voice. Some might carp at missing details —Rahul Ram, for example, barely finds a mention. Others will enjoy the bits about the early days, when the group found it difficult to get a place to practice without getting the neighbours all upset. Cultural histories are few and far between in India — to get one in the voice of the protagonist is welcome indeed. The book also has a bonus CD of his new group, the Susmit Sen Chronicles.

Sidharth Bhatia is a journalist and author of India Psychedelic: The Story of a Rocking Generation, a history of rock and roll in 1960s and ’70s India

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05