If a glance has critical intention, even a simple pencil line can have an individual entity of its own

Artist NS Harsha’s current mid-career retrospective in Tokyo is a testament to his intricate and layered oeuvre. He speaks about the importance of context, what it takes to critically engage with the world and coming into his own in Mysore.

A vast canvas: Harsha. (Courtesy: Mori Art Museum)

A vast canvas: Harsha. (Courtesy: Mori Art Museum)

In his detailed portrayals and multi-layered narratives, NS Harsha forges links between the local and the global, the traditional and the modern. The only Indian artist to have won the prestigious Artes Mundi award in 2008, he straddles various mediums with ease. If his figurative paintings have hundreds of protagonists on a flat visual backdrop, his site-specific installations and community-based art projects are often an outcome of his various social interactions. In what is arguably the most extensive showcase of his work, Mori Art Museum in Tokyo is hosting an exhibition, ‘NS Harsha: Charming Journey’, which comprises new works alongside other celebrated ones. The 47-year-old Mysore-based artist discusses his panoramic paintings, his influences and community-based work. Excerpts:

What went into the planning of this mid-career retrospective that showcases 20 years of your work?

Mami Kataoka, chief curator of Mori Art Museum, proposed the show in 2015. Initially, we didn’t know if it would be a retrospective. After Mami got to know more about my complex practice spanning various mediums — from painting, site-specific works and sculptures, to community projects and drawings — we felt it would be ideal to have a linear flow so that people can experience different aspects of my practice. The idea was not to show only ‘popular’ works. We were interested in creating a relationship between a sense of ‘time’ and my immediate surrounding.

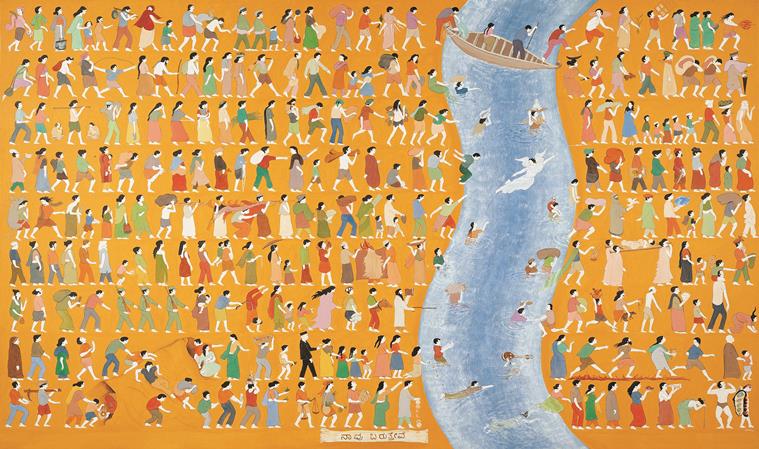

Several of your works have flat fields populated with hundreds of figures (for instance, We Come, We Eat, We Sleep; Come Give Us a Speech; and Mass Marriage). Could you discuss the origins of this approach? Are these figures real or imaginary?

In the early ’90s, during my college days, I was painting under the influence of the Transavantgarde Movement, but I didn’t feel very comfortable with it. So, I reverted to pencil and started all over again. Some of the local temple architecture, in which we find rows of repetitive forms but each one is different, interested me. I was also attracted to many of the eastern landscapes in which a ‘panoramic view’ of life is the key element. This led me to different fields, such as Vedic chants, minimalist music and so on — all these interests resulted in my present visual language, I suppose. It is a mix of human imagery that can be real, imagined or ‘automatic’ (figures drawn intuitively without thinking).

Each of the figures add to the narrative, but they form a unified picture in which some characters stand out.

I usually like to build a field full of individual events, so that they all, in a way, become flat from a distance but from up close, they have their own significance. This is the way our life, world and the cosmos is positioned.

In your work, you also reference the Japanese Manga and comic books from different regions. Were you interested in them during your childhood?

Yes, I have a collection of comics from my childhood and they played a significant role in my interest in drawing and paintings. At a later stage, I was also drawn towards popular posters and educational illustrations. With this background, I was excited when I came across the Manga culture in the early 2000s.

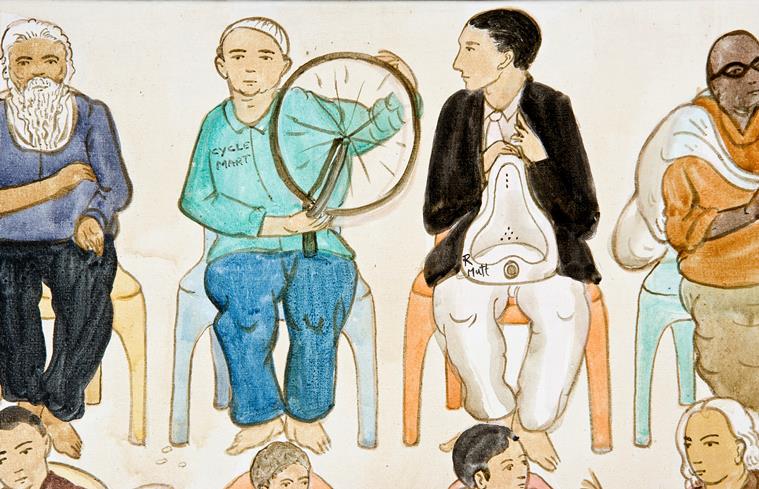

His work: Come Give Us a Speech. (Courtesy: Mori Art Museum)

His work: Come Give Us a Speech. (Courtesy: Mori Art Museum)

Several of your works borrow from Indian mythology, as well as events that take place around you. For instance, you had elephants in both Mooing Here and Now and Only Way Is through Milking Way, based on an incident where an elephant came into Mysore and killed five cows. How important is contextualisation for you?

For me, such local events reveal today’s global human condition. They reflect growing tensions between humans and nature. At the same time, such events unravel minute details of cultural conditions and contemporary challenges.

I believe you often take ‘conceptual walks’ in Mysore, where you visit different neighbourhoods. What exactly are these walks?

I have been going to the same market in Mysore since my childhood (Devaraja market). I initially went there to get comics and sweets with my father, then to buy vegetables for my mother, and later, to draw people. Then, I had to device a new reason to go to the same place again and again without getting bored. So, I came up with the idea to do ‘selective mind mining’ exercise, where I choose what I observe in my walk. Once I am out of the market, I don’t evaluate what I experienced. I leave behind that moment ‘in the market, for the market’.

You also seem to be intrigued by the cosmos. Your work has featured monkeys pointing to the sky, telescopes and the Milky Way. What about it do you find interesting?

Initially, I used to wonder about the mystery of this life and the world. But lately, I wonder, what is not ‘mysterious’? From a grain of sand to the cosmos, everything could be mysterious. So is human endurance to chase all these relentlessly. I feel lucky I can endure with paint.

You joined art school after you failed Class XII. Can you discuss your journey from Mysore to MS University, Baroda?

I was not that good in studies. I was interested in the science of things, but not the science that is taught in schools. So, I failed the pre-university exams. My parents encouraged me to join the local art school because of my skills. I wanted to get into motor racing, but I had some medical problems that did not allow me to go for it. So, I ended up in Baroda. It has been one of the foundations of my artistic journey — it exposed and enriched its students to global artistic knowledge, and encouraged them to follow their own paths. It was intense and deeply chaotic, but it encouraged us to look for the ‘self’.

His work: We Come, We Eat, We Sleep. (Courtesy: Mori Art Museum)

His work: We Come, We Eat, We Sleep. (Courtesy: Mori Art Museum)

There was a short period when you were based in Mumbai, but you moved back to Mysore. We see a lot of that city in your work. How important is Mysore to your practice?

I stayed in Mumbai and Delhi for a couple of months after moving from Baroda in 1995. But I felt I needed to go back to Mysore. I had this urge, I don’t know why. This city has become my ‘extended studio’. I travel, I gather thoughts around the world but then they all get formed and shaped here in this city. I spend a lot of time just loitering around, ‘looking’ and not thinking.

A lot of your work is also based on your interaction with local communities. You do a lot of workshops with children. How important are these engagements?

I observe communities. I don’t interact with them directly, like I do with children. For example, I go and sit in large gatherings (social, religious, political, etc) just to let my mind and body get exposed to them. I started conducting children’s workshops in the mid-’90s. But, I don’t do many now. I am revisiting my comfort zones in my practice at the moment. I need to think if I have become ‘clever’, which is not a great zone to be in in the creative process. Once I feel I am good at something, it is time to rethink and pause a bit.

I believe several of your works stay in your studio for years before you are satisfied with them. How important is it to self-critique?

The studio is not just a space to ‘make’, it is also a space for deconstruction. Intuition flows into the studio space to become forms and shapes. In the process, it meets several challenges — technical, social, cultural, political and so on. In this process, ‘time’ is infinite, so one never knows when things are ready to be shared with others in the social space.

Your work is often described as socio-political or ‘critical’. Would you agree?

During early and mid-2000s, I had a direct engagement with a few important human issues. But lately, I am moving into a different space which may not have a direct engagement with specific issues. I feel that even if a glance is embedded with critical and socio-political intention, even a simple pencil line can’t escape having an individual entity of its own.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05