Dance has to breathe, and it has to breath today’s air

Kathak dancer Aditi Mangaldas on her new production, refusing the Sangeet Natak Akademi award, and the need to contemporise classical dance forms.

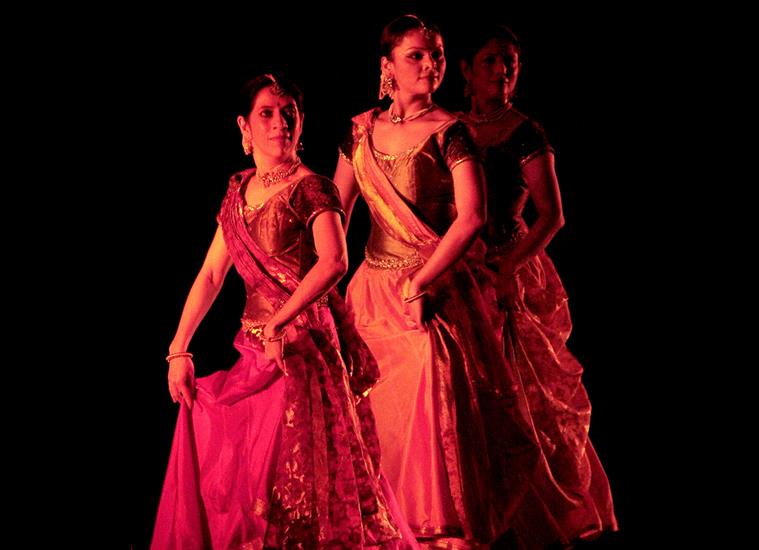

Dancing with the stars: Aditi Mangaldas (front) with the dancers from her repertory group, Aditi Mangaldas Dance Company.

Dancing with the stars: Aditi Mangaldas (front) with the dancers from her repertory group, Aditi Mangaldas Dance Company.

Going against the prevailing conventions in Indian classical arts is bound to draw brickbats and bouquets in equal measure, and such has been the experience of Aditi Mangaldas. The 56-year-old Kathak dancer has achieved international acclaim for using the strong foundation of classical dance to address contemporary concerns. The Delhi-based artiste has choreographed pieces such as Within (2013), prompted by the 2012 gangrape in Delhi, and Now Is (2010), where she explored what it means to live creatively in the “now”, and for which she collaborated with Shubha Mudgal, Aneesh Pradhan and Wendell Rodricks. Her production, Inter_rupted, which premiered last week in Mumbai, is the latest in a line of works that melds a classical idiom with innovative choreography. It is is slated to tour Germany and Britain in October this year. Excerpts:

What ideas does your latest piece, Inter_rupted, explore?

Inter_rupted emerges from the body; it talks about the fragility of the body, its inevitable transformation and resilience. As the body disintegrates, where does the ‘self’ go? Where do thoughts and emotions reside? These are the questions that the piece asks.

Is this based on personal experience?

All my works begin on an autobiographical note. I’m usually inspired by something that happens around me, or concerns me. Or, it could be a personal incident. I work on it and hope that the personal experience embraces the wider, human one. With Inter_rupted, the experience was about noticing how the body changes over time. It’s neither negative nor positive. It just is, and there is a beauty in that. There’s a beautiful quote by Buddhist monk Pema Chödrön, where she says that we are attached to this body thinking that it is a continuous, reliable entity. But when we probe this attachment a little deeper, we wonder what it is we are trying to protect.

It seems apt that the vulnerabilities of the body should be addressed through dance.

For dancers, the body is the instrument. This includes the physical, emotional and the intellectual body, and the disintegration of all these is a part of a dancer’s existence.

You’ve worked with a number of collaborators on Inter_rupted. How did the team come together?

Farooq Chaudhry (producer of the Akram Khan Dance Company) is the dramaturge, Morag Deyes (artistic director of Scotland-based Dance Base) is the mentor, Italian lighting designer Fabiana Piccioli is there too, along with Kimie Nakano (Japanese film and theatre costume designer), the costumier, and Delhi-based Manish Kansara on stage design. I have worked with all of them before, but this is the first time that they have all been involved right from the conception stage, which was over a year ago.

How does having collaborators work with you right from the beginning change the process?

It’s far more intense because they question constantly, never allowing you to get complacent. When you are working alone, you are the dancer and the choreographer, it gets very difficult to stand aside and look at the work as a whole, objectively. You get exhausted, your crew gets exhausted too, and that makes you suppress any questions that might arise. But here, you get creative inputs right from the beginning and it makes the piece more textured.

A scene from Mangaldas’s latest contemporary production, Inter_rupted.

A scene from Mangaldas’s latest contemporary production, Inter_rupted.

After you declined the Sangeet Natak Akademi award in 2012, there was much debate about the definition of classical Kathak.

I didn’t ask for the award when they gave it to me in the Creative and Experimental Dance category. My work is based entirely on Kathak — 80 per cent of what I do is classical Kathak and 20 per cent is my contemporary work based on it. The award showed the narrow mentality of the committee, so I didn’t accept it.

I have also been asked how I can call myself a Kathak dancer since I don’t wear a dupatta. I was told that Kathak is three-dimensional and that the dupatta adds grace. Men don’t need to dance with a dupatta. Does that mean they are born with grace and women are not? I can see how sound adds dimension, how emotions add dimension, but how can a piece of fabric do that? I find that regressive. When I was 16 and doing my first solo at the Kal Ke Kalakar festival under my guru Kumudini Lakhia, I didn’t wear a dupatta, nor did I wear one when dancing in many of (Birju) Maharajji’s pieces.

How do you define classical Kathak?

Classical does not mean ‘carved in stone’. It’s a river that flows continuously and rejuvenates itself. When the original kathakas went from the temples to the Mughal court, they adapted and expanded their technique. Some of what we perform today as classical Kathak was non-existent in the temples. But they’re now a part of our repertoire. Dance isn’t something that drops from the heavens; it is a living, evolving tradition and conservation of this tradition lies in constant, responsible change, not in cementing the norms. There is a complete paranoia that we are going to lose our heritage if we expand its boundaries, but we will actually lose it only if we put it in a museum and don’t let it breathe. Kathak tradition has deep roots, but we should water it with contemporary sensibilities and concerns.

Do you feel the classical arts in India are opening up to these contemporary sensibilities and concerns?

Artistes have a great responsibility. The world is becoming smaller, and in response, our concerns have to grow. There is a difference between being a performer and an archivist. An archivist worries about whether an idiom belongs to, say, the Jaipur or the Lucknow gharana, or whether something was done in the 15th or the 16th century. But dance has to breathe, and it has to breathe today’s air.

What is your opinion of the grading system for artistes that the culture ministry has recently announced?

What I want to know is who is going to do this grading? What is the criteria? Is it an artiste’s popularity, excellence, number of students, number of performances, or the international acceptability? Are they only going to grade these ‘archivists’? Honestly, there has to be a more in-depth approach.

So how do you see the government’s role, given that it is the biggest patron of the arts in the country?

The government has to grow up. You can’t just pull classical dancers out of a box and put them on display, saying, “Dekhiye, hamara heritage, hamara Indian-wear (Look at our heritage, at our Indian-wear).” They need to ask how dancers are surviving, what the infrastructure is, and the global outreach. Where are the venues for performing and the rehearsal spaces? What is happening to those who dedicate their lives to dance, and then can’t perform? Is there any insurance for these performers, teachers and gurus?

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05