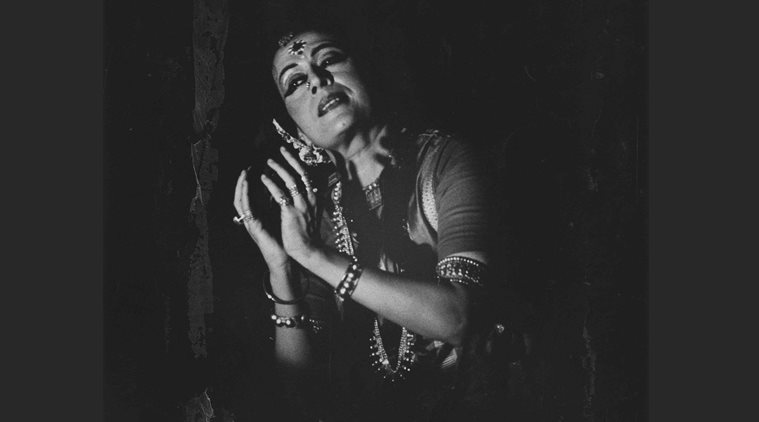

Colours of Her Life: Bharatanatyam and Odissi exponent Sonal Mansingh on her dance, being branded saffron

Sonal Mansingh on being labelled a “sanghi” innumerable times, her stint as the chairperson of the Sangeet Natak Akademi and her inclusion in Modi’s navratnas, the creation of the Swachh Bharat production, reconstitution of the Central Advisory Board on Culture (CABC).

“People are welcome to call me what they like. ‘Arrogant’ and ‘saffron’ are two words I hear often. I don’t really care anymore,” says Sonal Mansingh.

“People are welcome to call me what they like. ‘Arrogant’ and ‘saffron’ are two words I hear often. I don’t really care anymore,” says Sonal Mansingh.

Sonal Mansingh is perched on her favourite chair in the living room of her second-floor apartment in Delhi’s Defence Colony. She says this is the one spot from where she’s able to see the trees, the birds and the sky — “enough to stimulate my creative process.” Dr Sheldon Cooper would approve. Not that Mansingh cares at all about the famed pop icon. “I’m unpopular because I don’t care much about the popular,” says the 73-year-old Bharatanatyam and Odissi exponent.

“Ninety per cent of the times I don’t allow interviews, especially at home. But I’m glad you didn’t ask me when was I born and who taught me dance. We are good to go,” says Mansingh, adding she has little patience for “unintelligent questions”.

Her recent production, titled Divyalok – Abode of Divinity, which was presented at Delhi’s India Habitat Centre earlier this month, saw her as a narrator while repertory dancers of the Centre for Indian Classical Dances, a dance institute run by Mansingh, performed the Bharatanatyam piece. The production, which faltered due to under-prepared dancers and clunky narration, was an ode to the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan and a consequence of her nomination by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014 as one of his navratnas for the campaign. “I didn’t want to make it a mere photo opportunity, posing with a jhaadu like many did. That kind of stuff doesn’t sit well with me. I wanted to contribute through art. But yes, the production needs to be polished a lot more,” says Mansingh. While Kaaliya Mardan, a section in the production, talks of a polluted Yamuna, a lot of it focuses on cleanliness of thought, action and speech.

Her creative process at this stage, says Mansingh, deals with definite ideas. “My work is well cut out —women, environment, the tribals and jail reform, among others,” she says.

Her inclusion in Modi’s navratnas, the creation of the Swachh Bharat production, reconstitution of the Central Advisory Board on Culture (CABC), which has her as a member now, and a very controversial stint at the Sangeet Natak Akademi as its chairperson in 2003, following former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s recommendation, have all led to her being labelled a “sanghi” innumerable times. “There is a judgmental avalanche that has started every which way. It’s not right, left and centre. People are welcome to call me what they like. ‘Arrogant’ and ‘saffron’ are two words I hear often. I don’t really care anymore,” says Mansingh.

It was after her marriage to bureaucrat Lalit Mansingh that her then father-in-law introduced her to Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra and Odissi became an integral element of Mansingh’s life.

It was after her marriage to bureaucrat Lalit Mansingh that her then father-in-law introduced her to Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra and Odissi became an integral element of Mansingh’s life.

It was during Emergency in 1975 that her political leanings became evident for the first time. “After that, no awards or grants were given to me. After the Indira Gandhi government, it was the Rajiv Gandhi government, so the ban on me continued. No accommodation was ever allotted for me,” says Mansingh, whose house in Defence Colony is rented. She adds how Mani Shankar Aiyyar, who was friends with her— “still is, and was Rajiv’s man Friday”— recommended her name for the Rajya Sabha. “But Rajiv would tell him that I am against his mother. ‘How can I put her in the Rajya Sabha?’” says Mansingh.

It was when she accepted an invite extended by Vishwa Hindu Parishad to perform in Washington to mark the 100th anniversary of Swami Vivekanand’s Chicago address along with Kishore Kumar, Anuradha Paudwal and Anup Jalota in 1993 that matters came to a head. She says she was “summoned” to Delhi’s Mavlankar Hall, where fellow members of “Artists Against Communalism”—Kuldip Nayar, Shabana Azmi and members of Sahmat, among others — questioned her. “I told them that as long as no one was dictating the content of my performance, I didn’t care who invited me. I went and danced in the US. They said saffron hai. I said call me what you want,” she says.

Moving around in the corridors of power wasn’t new for Mansingh. Having grown up in a Gujarati home with Mangal Das Pakvasa, a freedom fighter and one of the first five governors of India, as her grandfather, Mansingh found easy access to many politicians and legendary artistes and imbibed a lot from their constant presence in her life. “They say she has political connections. What they don’t realise is that I knew people like Vasant Sathe, NKP Salve, George Fernandes, and Anant Kumar Hegde initially because of my family and my grandfather and then because of dance. I grew up in this mahaul. It never seemed unnatural to me. Painters, journalists, politicians, and artistes would come home and we’d talk. Such interactions don’t happen anymore. Those were brilliant times,” says Mansingh, who grew up watching legends and family friends, such as MS Subbulakshmi and Rukmini Devi Arundale perform in her living room.

“Darbar Hall in Raj Bhawan was always teeming with artistes and it was naturally a learning process,” says Mansingh, who began learning Manipuri at four and Bharatanatyam at seven. But even after training for years and a hugely successful aarangetram, at 18, a career in dance was opposed by her family. “So I ran away,” says Mansingh, with a throaty laugh. She went to Bangalore and began learning from US Krishna Rao and Chandrabhaga Devi. She later learnt abhinaya from the famed Mylapore Gowri Ammal. “A lot of people call it a bold step, this running away business. I just took a bus to Victoria Terminus and then changed two trains,” says Mansingh. It was after her marriage to bureaucrat Lalit Mansingh that her then father-in-law introduced her to Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra and Odissi became an integral element of Mansingh’s life.

But life took a turn after her divorce in 1973 and her decision to not accept alimony. In her recent biography, Sonal Mansingh: A Life Like No Other (Penguin Viking), author Sujata Prasad writes, “She remembers taking overdrafts from her bank, selling off gold bangles gifted by her mother and borrowing money from well-wishers like OP Jain and AJ Jaspal to pay her musicians.”

Dance, she says, is what kept her going. “The government offered no support. I wrote letters to everyone, even to PM Manmohan Singh, but didn’t get anything,” says Mansingh.

In 1972, she met Georg Lackner, director of Goethe-Institut at Max Mueller Bhawan in New Delhi for the first time. On her subsequent trips to Europe, the two spent a lot of time together, gorging on pretzels and exploring various dance opportunities for her. Lackner helped organise many performances for Mansingh.

She was in love and was happy that she wasn’t being judged like she was in India. “I’m so happy and fulfilled with Georg that sometimes I don’t wish to think about the difficulties I face in Delhi,” Mansingh had written to her friend Kumkum. According to Mansingh’s biography, as soon as Indira Gandhi learnt of the relationship, Lackner was transferred to Goethe-Institut, Montreal. “It wasn’t a bad deal in retrospect. I had a terrible car accident around the same time. And because Georg was in Canada, I got treated there and was able to dance again. It all worked out,” says Mansingh, who always missed India and eventually decided to return.

Upon her return, she threw herself deep into her work, which resulted in stellar productions such as Draupadi (1994), Indradhanush (1999), Geeta Govind (1987) and Ashta Nayika (1980) among others.

When she became the chairperson of Sangeet Natak Akademi in 2004 on the recommendation of the then NDA government, there was discontent. Sixty artistes signed a letter of protest and sent it to former President APJ Abdul Kalam. While there were talks of Mansingh’s dictatorial behaviour, there were many resignations, including that of Carnatic legend M Balamuralikrishna, vocalist Ajoy Chakraborty and Bombay Jayshree among others. Bhupen Hazarika wrote to the president saying that Mansingh played “a cruel and manipulative game” in ousting him. Mansingh says, “While the insiders didn’t like that I followed rules, the artistes had their own agenda. You cannot please everyone.” She was called to Rashtrapati Bhawan for a final conversation with Kalam. “He told me, ‘Sonalji you are more than just a capable administrator. But this is the third time the file has come to me and I don’t have a choice but to sign it’. But even in that process, he cut the word ‘removed’ and wrote ‘replaced’ on top. I was teary-eyed. I’ll never forget the grace he accorded to an artiste,” says Mansingh.

In tough times, Mansingh has always turned to her work. The past few years haven’t been any different. In the last decade she has produced Intezaar (2005), Ujjawal Asha (2009) and Pancha Kanya (2017). Currently, she is busy polishing the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan choreographies and working on two more productions. “I won’t discuss those. Come and watch when they are done,” she says.

Where the Rhythm Takes You

Sonal Mansingh belongs to a generation of immensely talented and eloquent female dancers from the post-Independence era who were exceptional when it came to their art form, who represented India globally and were seen as much in power coteries as they were in famed social soirees and in the thick of controversies.

A Sanskrit scholar, a graduate in German literature with a working knowledge of every Indian classical dance form, one of Mansingh’s greatest contributions to classical dance is perhaps getting north Indian texts included into a more Telugu and Tamil centric repertoire of Bharatanatyam —a form that north India found very hard to understand about five decades ago.

Culture historian Sunil Kothari, who has seen Mansingh evolve from the ’60s, calls her a fine dancer. “She came under the spotlight alongside dancers like Yamini Krishnamurthy. Her technique, the execution on stage was all in place. Her brilliance was also in the way she understood rhythm and moved with it. The lines, the form, the technique — they were all there and led Mansingh to the pinnacle,” says Kothari.

But in the last few years, critics have also raised questions over her performances. Many have pointed out her failed reinvention as a storyteller as a subject of concern. Kothari, however, refuses to comment on her recent years in dance.

“I’d rather not,” says Kothari, who had famously criticised her Naatya Katha (2011), calling it a performance with storytelling that “has no depth, does not touch the hearts… and does not leave a lasting impact”.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05