📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

Bertolt Brecht: Transcending borders, times through theatre

World Theatre Day: The German theatrecian and playwright works spoke against oppression and discrimination, and for the downtrodden, which could easily find a context in post-independent India

Brecht was a vociferous critic of fascist forces – and this reflected in the plays he wrote. (Pic source: Pixabay)

Brecht was a vociferous critic of fascist forces – and this reflected in the plays he wrote. (Pic source: Pixabay)“I’m not writing for the scum who want to have the cockles of their heart warmed”

– Bertolt Brecht, German theatrecian and playwright, July 30, 1926.

As the third bell rings and the strings of the stage curtains are pulled, one side of an otherwise pitch-dark theatre brightens up with soft light beams falling directly on stage. Within minutes into the play, the audience is caught in the same dilemma as the protagonist. They laugh, cry and feel enraged together with the character and reach the zenith of emotions as the climax nears. The play ends with a huge round of applause with tears welling up in the audience’s eyes.

For years, this has been an ideal ending to a “successful” theatre show, aimed at captivating the audience with the aura of acting skills, soul-stirring storyline and script, and an execution apt to complement all these to arouse emotions of the audiences.

German theatrecian Bertolt Brecht, however, chose to disagree. And he did this by introducing his own form of writings, and methods of execution. Brecht was born into a Bavarian family in Germany in 1898. When World War I broke out in 1914, a 16-year-old Brecht started working as a medical orderly in the German military services. While he himself kept safe, he lost a number of friends to the armed aggression. In the 1920s, Brecht struggled financially due to excessive inflation. As Hitler assumed power in Germany in 1933, Brecht had to leave for Denmark with his family. They continued to flee many countries with Nazism growing stronger in the years that followed. When World War II ended, and the Cold War began, Brecht was put under FBI scanner.

Bertolt Brecht and Helen Weigel on the roof of the Berliner Ensemble during the International Workers’ Day demonstrations in 1954. (Photo: Horst Strum/German Federal Archives/Wikimedia Commons)

Bertolt Brecht and Helen Weigel on the roof of the Berliner Ensemble during the International Workers’ Day demonstrations in 1954. (Photo: Horst Strum/German Federal Archives/Wikimedia Commons)

A person to have closely experienced all these catastrophes of the twentieth century, Brecht was a vociferous critic of fascist forces – and this reflected in the plays he wrote. This World Theatre Day, we revisit his contribution to theatre and what his plays hold for today – 125 years from his birth.

Epic Theatre and distanciation

The fundamental architect of Epic Theatre or, as he says, the scientific theatre as against the classical theatre that has empathy leading to theatrical catharsis, Brecht believed in critical viewership, by means of distanciation of the audience from the storyline of the act.

In Brecht’s words: “The essential point of the epic theatre is perhaps that it appeals less to the feelings than to the spectator’s reason. Instead of sharing an experience, the spectator must come to grips with things.” His plays were written, and designed likewise.

Brecht wanted audiences to be alert, put their grey cells to use in order to understand the gravity of the situation, on which the play is based, instead of just flowing with the emotions acted out. “The one tribute we can pay the audience is to treat it as thoroughly intelligent,” he said in an interview with Bernard Guillemin on July 30, 1926. According to French Philosopher Louis Althusser, “He (Brecht) wanted to set the spectator … (as) an actor who would complete the unfinished play, but in real life.”

To distanciate audiences, he used tools such as matter-of-fact acting, moving sets while the play is on, using an actor in multiple characters, actor-audience interaction, among others.

A still from Sahityika Santiniketan’s production ‘Ihudi Stree’, translated from Brecht’s ‘The Jewish wife’. (Pic source: Sahityika Santiniketan)

A still from Sahityika Santiniketan’s production ‘Ihudi Stree’, translated from Brecht’s ‘The Jewish wife’. (Pic source: Sahityika Santiniketan)

In 1928, when The Threepenny Opera was staged for the first time in Berlin, Brecht used specific stage setups that would have a distanciation effect on the audience. A fitting representation of the hypocrisy among the upper-class, Brecht’s comic timing, and Kurt Weill’s ballads instantly struck a chord with the audiences in the post World War I era.

Brecht in India

With communist leanings, Brecht’s works spoke against oppression and discrimination, and for the downtrodden, which could easily find a context in post-independent India. Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera was made into ‘Tin Paisar Pala’ – by Bengali theatre group Nandikar’s Ajitesh Bandopadhyay in the 1970s contextualising it in the post-Sepoy Mutiny period. Over the years, the play has seen multi-lingual adaptations across India critiquing the bourgeoisie in capitalist society.

Badal Sircar, the father of the Third Theatre movement in Bengal, adapted Brecht’s ‘Caucasian Chalk Circle’ into ‘Gondi’, and staged it for the first time in 1978. A closer look at Sircar’s Gondi and other productions show that he was amply influenced by the German dramatist. Sircar looked for spaces other than proscenium to perform his plays, breaking the imaginary fourth wall that separated the actors from the audience. With minimum grandeur in plays in terms of lights, props and costumes, he broke the illusion the traditional theatre had created.

A poster of ‘Tin Paisar Pala’ — an adaptation from Brecht’s ‘The Threepenny Opera’ by Sangharam Hatibagan. (Photo: Facebook@ Tin Poisar Pala)

A poster of ‘Tin Paisar Pala’ — an adaptation from Brecht’s ‘The Threepenny Opera’ by Sangharam Hatibagan. (Photo: Facebook@ Tin Poisar Pala)

Eminent dramatist Girish Karnad too sought refuge in Brechtian formats in his plays. In their paper “Impact of Brechtian theory on Girish Karnad: An Analysis of Hayavadana and Yayati”, Deepa Kumawat and Iris Ramnani points out that: “Considerably disillusioned and dissatisfied by the established theatre he (Karnad) chose the ‘epic theatre’ as proposed by Brecht which heightens the alienation effect in the audience.” According to Kumawat and Ramnani, Karnad successfully adopted the Brechtian dramaturgy by employing history to achieve “alienation effect”. “Efficiently using the mythological traditions in his plays Karnad has tried to modernize his themes, focusing on the identity crisis in Hayavadana (1971) and malcontent in Yayati (1961),” they wrote.

Brecht in 21st century

It’s the 21st century, and Brecht’s pieces are still regularly performed in Japan, Poland, Togo, India and many more countries. For instance, “Mother Courage and Her Children ” from 1941 is being staged in Lome, Togo, Deustche Welle reported. The story revolves around a mother who tries to get her children through a war safely.

In India, Imaad Shah debuted as a theatre director with Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera in Mumbai in 2017. Around the same time, Kolkata-based Sangharam Hatibagan took ‘Tin Paisar Pala’– Ajitesh Bandopadhyay’s Bengali adaptation of The Threepenny Opera – to stage.

Bengaluru-based Kahe Vidushak Foundation too adapted Brecht’s Thereepenny Opera into Do Kaudi Ka Khel in 2019. Director Srinivas Bessety traveled all across the country with the production – that was translated in Hindi by Parimal Dutta. Choreographed by Ankita Jain, Chhau dance form was used as a crucial tool for execution of his musical.

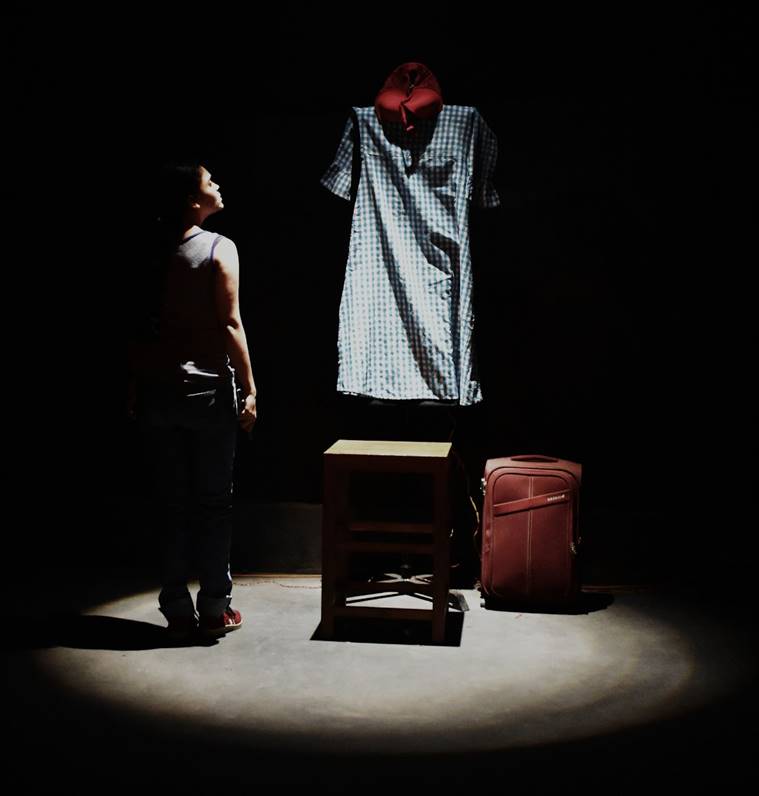

‘Ihudi Stree’ being performed at a non-proscenuim space in Santiniketan. (Pic source: Sahityika Santiniketan)

‘Ihudi Stree’ being performed at a non-proscenuim space in Santiniketan. (Pic source: Sahityika Santiniketan)

As 2023 marks the 125th year of Brecht, the world politics playing out around us gives us no reason to deny his relevance today, say theatre workers. Pritha Chakraborty, working with Bengal-based theatre group, Sahityika Santiniketan, says, the historical context to which Brecht belonged could be seen to be reflected in all his works. “The racial crime, racial hatred, which he was a witness to in Germany is still very much prevalent among us, around the world,” says Chakraborty, who plays a young Judith in ‘Ihudi Stree’, a Bengali translation of Brecht’s ‘The Jewish Wife’, which the group premiered in February this year.

The play shows a hassled Jewish woman, Judith, going through an emotional rollercoaster as she packs up to leave her non-Jewish husband and, of course, her own country. This, because the government had disowned her for being a Jew, and staying with her husband could put him and his reputation in trouble. Sahityika Santiniketan, in its play, has split the character into three, of different ages each, to capture different time periods.

Chakraborty also points out that whenever there is a crisis – be it a racial or environmental crisis, or forced migration, it affects women more than it affects men. “For women, it is a double marginalisation. This way, ‘The Jewish Wife’ stands the test of time,” she says.

Debanshu Majumder, the play designer, says, “We hadn’t planned the play for Brecht’s 125th birth year though. Brecht, as an observer and survivor of various turbulent times in his life, has left accounts of various kinds of oppression – be it social, cultural, political and even gender, in his plays. So, his content is always relevant.” Talking about The Jewish Wife, Majumder says, “Brecht wrote this play around 1936 when the seeds of World War II were already being sown. Around this time, German Jews were being subjected to religious atrocities forcing them to leave their country. This has a striking resemblance with today’s India where the state is trying to define citizenship under new terms, and identify people belonging to a specific religion as “the other” using NRC-CAA. Hence, we felt the need to address this issue through this play.” The group used three satirical cartoons – on Black Lives Matter, International border crisis, and NRC-CAA – as parts of their set that get revealed at the end of the play to connect it with the present world context.

📣 For more lifestyle news, follow us on Instagram | Twitter | Facebook and don’t miss out on the latest updates!

📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05