Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

One night at a Delhi hospital: Sanjay Gandhi Memorial Hospital

Government doctors in Delhi went on a strike last month demanding security, fixed hours and basic equipment. The Indian Express tracks 4 doctors in 4 hospitals. Concluding part of series.

A doctor checks an X-ray in the ER of Sanjay Gandhi Memorial. (Source: Express photo by Oinam Anand)

A doctor checks an X-ray in the ER of Sanjay Gandhi Memorial. (Source: Express photo by Oinam Anand)

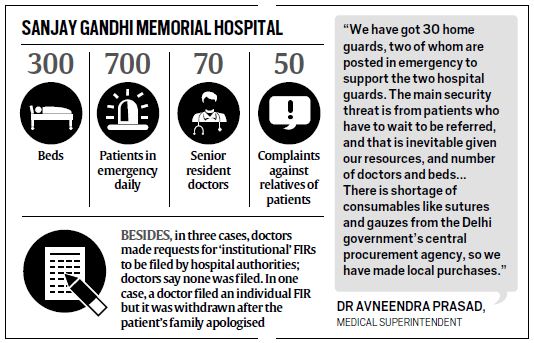

In the last three months, emergency doctors at Sanjay Gandhi Memorial Hospital in North West Delhi have sought filing of three FIRs and registered around 50 complaints against relatives of patients. A few months ago, the television outside the ICU was smashed by relatives of a woman who came in after an abortion gone wrong. Doctors locked themselves inside the ICU duty room to escape.

Last month, when resident doctors across government hospitals in Delhi went on a strike, security from angry patients was their immediate concern. Short of beds, doctors, drugs, and even consumables such as sutures, gauzes and surgical blades, the 300-bed Sanjay Gandhi Memoral Hospital, that is the first point of treatment for people in most parts of North West Delhi, knows what it is to be at the receiving end.

[related-post]

The hospital receives medico-legal cases (MLCs) from 17 police stations in the area. In a typical emergency shift, doctors see at least 80 MLCs, including accidents, falls and stabbings.

When patients start pouring in around 9 pm, the start of the peak period of the night shift, there is usually no time for triage — separating them as per degree of emergency. Those who can be immediately treated are looked at first. Those who need tests have to wait till arrangements are made; those who can pay, go to nearby private centres and get them done on own.

Around 10 pm, the brother of a teenager hit on the head with sticks and found lying in Sultanpuri is fighting with Dr T (name withheld to protect identity). The surgery resident, Dr T, who is dealing with another patient bleeding from a foot after a bike ran over it, tells him for the third time that his brother needs a CT scan and he has to wait. Since CT scans are not done in the hospital, there is a tie-up with a private diagnostic centre in Rohini, about 10 km away. Dr T tells him an ambulance will take them to Rohini and get them back with the reports. It all will be free, the hospital will bear the costs, the doctor adds.

Around 10 pm, the brother of a teenager hit on the head with sticks and found lying in Sultanpuri is fighting with Dr T (name withheld to protect identity). The surgery resident, Dr T, who is dealing with another patient bleeding from a foot after a bike ran over it, tells him for the third time that his brother needs a CT scan and he has to wait. Since CT scans are not done in the hospital, there is a tie-up with a private diagnostic centre in Rohini, about 10 km away. Dr T tells him an ambulance will take them to Rohini and get them back with the reports. It all will be free, the hospital will bear the costs, the doctor adds.

The brother is not convinced. As Dr T sutures the last two toes of the bleeding victim, he pleads, “My brother will die by then. Just treat him, he is only 19.” Dr T again tries to argue, “If we operate him without a scan, we can cause more damage.”

By now, the brother is aggressive. “Is this private centre paying you to get tests done?” he says. “You don’t know who I am, everybody here knows me. If you don’t treat my brother, I will come back with more people.”

Two home guards, posted outside the emergency since last month’s strike, are hastily summoned. As the brother pipes down, an intern calls up the Rohini centre again, adding in a whisper that the patient’s relative is “getting agitated”.

Dr T by now has a six-year-old child with a head injury, unconscious and bleeding, in his arms, handed over to him by his mother. After attempting to clean the wound in the minor OT, Dr T again contacts the Rohini centre, as well as another in Punjabi Bagh, 15 km away, for CT scans. When both say the procedure will take five-six hours, Dr T calls up other government hospitals. His friend, on duty in the emergency at Safdarjung Hospital, 30 km away, promises to take care of the child. Hearing Dr T arranging to move the child, the mother falls down on all fours, begging him not to send them away. The father starts screaming at the doctors.

Dr D, the chief medical officer and seniormost in the emergency, tries ineffectually to intervene. Eventually one of the guards takes the father outside, while the mother sobs.

However, doctors understand their anger. Any reference to Safdarjung Hospital for tests means an additional five hours before treatment. While some tests can now be done in emergency — including serum sodium, serum potassium etc — patients have to get them done from outside for elective surgeries. Ultrasound is not available in the emergency, while the single ventilator is not working.

The nine beds in the main emergency are by now occupied by five times the number of patients. The single desk for doctors is placed against a wall, around which residents of different disciplines and a medical officer sit. By 11 pm, the medical emergency ward on the first floor has 43 patients in 29 beds.

As frustration grows on both sides, explanations fall on deaf ears. One common argument concerns the oxygen cylinders in the ICU, where critical patients from emergency are shifted. The hospital still does not have a centralised oxygen supply system, and the relatives keep alleging the cylinders allotted to their patients are not working.

At around midnight, a 23-year-old stabbing victim with compound fractures is being examined in the minor OT of emergency, as the single major OT is occupied due to a Caesarean. Dr D is trying to win another losing argument with three of the patient’s attendants, telling them to go to a private lab that will run free tests for them for electrolytes and blood group. As seven other patients crowd around him, Dr D tentatively suggests that the family get other tests done as well. “There are some blood-to-blood infections which can be transferred from the patient to the doctor, like Hepatitis C and HIV. Please get tests for these done yourself,” he says. If a patient tests positive for these infections, surgeons must wear additional protective gowns and gloves.

The family says a flat no. “When our son is dying, why should we waste time on tests to protect doctors? You call your seniors. Why did you become doctors if you are so scared?” the murmurs grow, soon picked up by others in the crowd.

Dr D decides the surgery would have to be conducted without the tests.

Last year, a senior anaesthetist at the hospital had contracted Hepatitis C and had to spend around Rs 70 lakh in treatment, with no financial help from the government as he continues to be on contract since 2008.

Still, when a couple of months ago, a resident doctor in the emergency asked a patient to get HIV and Hepatitis C tests done outside, he was slapped with an inquiry.

In the course of the night, arguments break out with at least three patient attendants over blood tests. One tries to grab a doctor’s collar when he is told the OT is out of surgical blades.

When a 64-year-old cardiac arrest patient succumbs, Dr D sends out an intern to get the home guards before declaring him dead. They accompany the 15 attendants of the patients inside, trying haplessly to control them. Announcements of death are always a security risk, Dr D says wryly.

The other doctors have started moving slowly towards a barely discernible spot next to their desk by now. It is the opening to a secret back exit, created after recent incidents of violence. Every time the crowd gets restless, doctors take this route as the guards lock the front gate of emergency.

It’s 1 am, and outside, two women gynaecology residents are walking the 200 metres from the gynaecology emergency to the OT in the main emergency building for their fourth Caesarean of the night. On both sides, men are sprawled, playing cards. As they rush with the patients, some of the men start jeering, “Doctor saheb coat nahin pehna aaj aapne. Thand nahin lag rahi?”.

The parking reserved there for doctors has been taken over by taxis and autorickshaws — another potential security risk.

No guard can be spared to protect them here.

All doctors in emergency learn some unwritten rules over time, Dr T smiles. “When to run, what tests to order, and which drugs to do without.”