It was just a 14-km favour for a friend on a hot, dusty April day in the early 1980s. Chandra Shekhar Choudhary says his long-time acquaintance Anirudh Choudhary asked him for a drop to Kharagpur block’s Shashan village, about 14 km from Tarapur, on his motorcycle on April 19, 1983.

At his house, located in Bihar’s Munger district, Anirudh asked 18-year-old Shekhar, who had just enrolled in a Munger college for graduation, to have a cup of tea before riding back to Tarapur. With the last sip of his tea, Shekhar’s life as he knew it disappeared forever.

“About 10 persons, some of them armed, barged into the room. A country-made pistol was shoved in my face and a man declared that I was being kidnapped for marriage. I suddenly realised that Anirudh had disappeared while I was having tea,” recalls Shekhar.

Pakdua vivah or forced marriages at gunpoint were not unusual in Bihar, especially in Munger, Khagaria and Begusarai districts in the 1980s and 1990s. However, this outdated practice refuses to remain a thing of the past. On November 29 this year, Gautam Kumar, a newly-appointed government teacher at a school in Vaishali district’s Repura village was kidnapped at gunpoint and forced to marry a woman in her early 20s. Kumar has refused to accept the marriage, saying that he felt emboldened by a recent Patna High Court verdict setting aside a 10-year-old pakdua vivah of a Nawada-based Army personnel to a Lakhisarai woman, the High Court had said that “until saptpadi (seven steps or saat phere) is performed or a marriage consummated, it cannot be called a marriage”.

Shekhar blames the recent flurry of teacher appointments in Bihar and the dowry system, which he says drives desperate relatives to kidnap eligible bachelors even today. “I’m glad men are going to the police and court for help. In the 1980s, including in my own case, seeking police help was considered as good as public shaming. Community intervention was the only way out then,” he says.

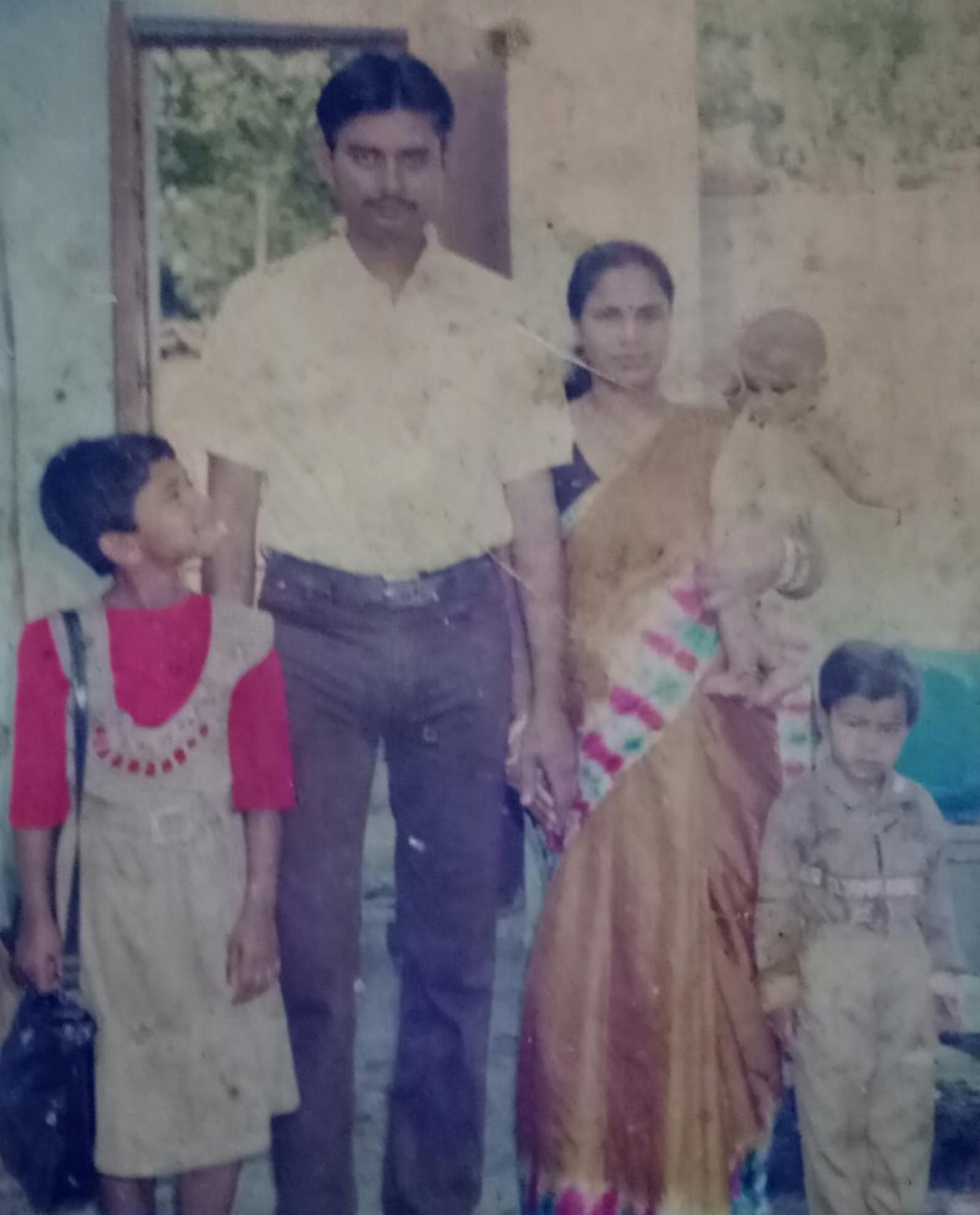

Chandra Shekhar Choudhary was 18, while Baby Choudhary was just 13 years old at the time of their pakdua vivah or forced marriages at gunpoint in April 1983. (Express photo by Santosh Singh)

Chandra Shekhar Choudhary was 18, while Baby Choudhary was just 13 years old at the time of their pakdua vivah or forced marriages at gunpoint in April 1983. (Express photo by Santosh Singh)

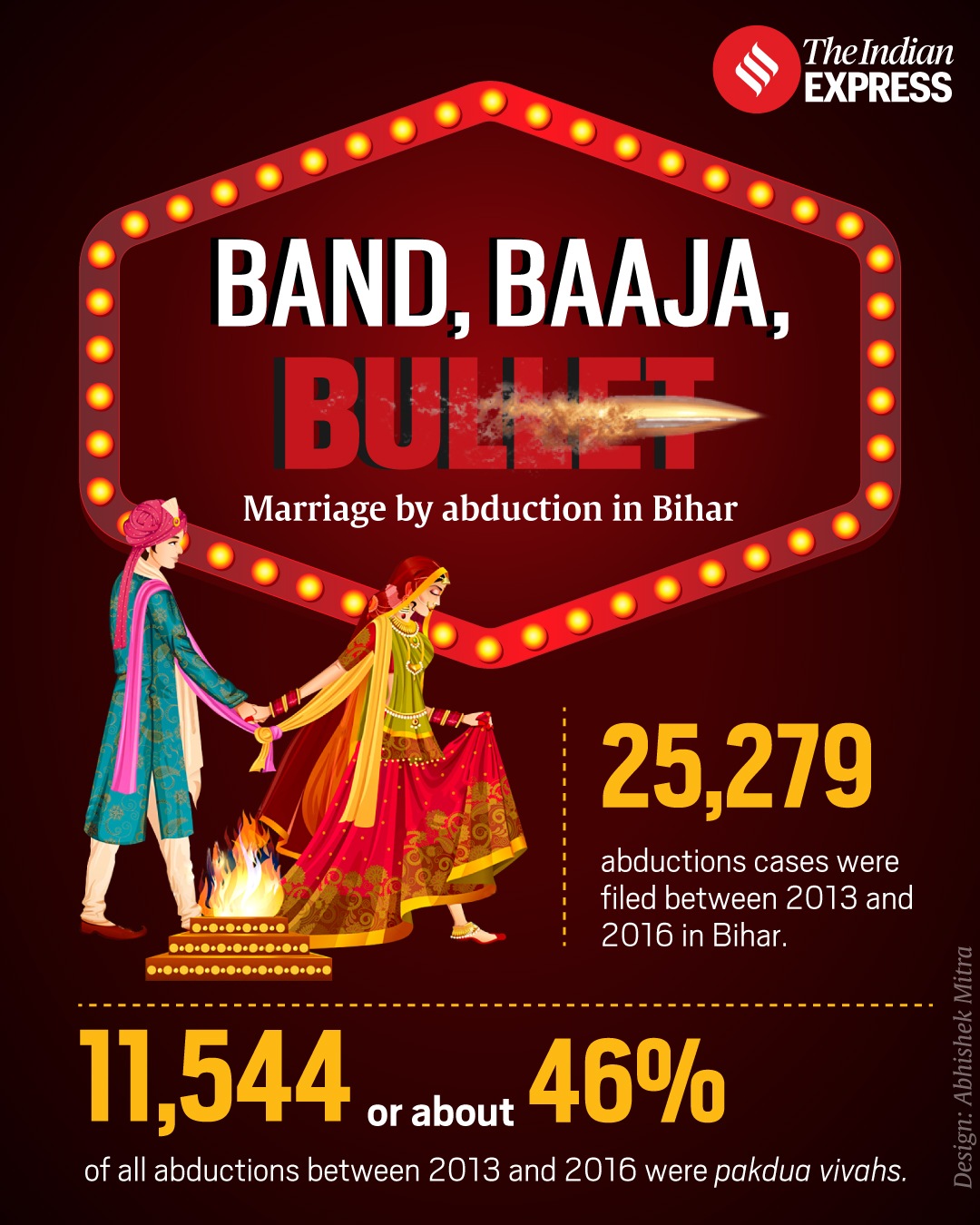

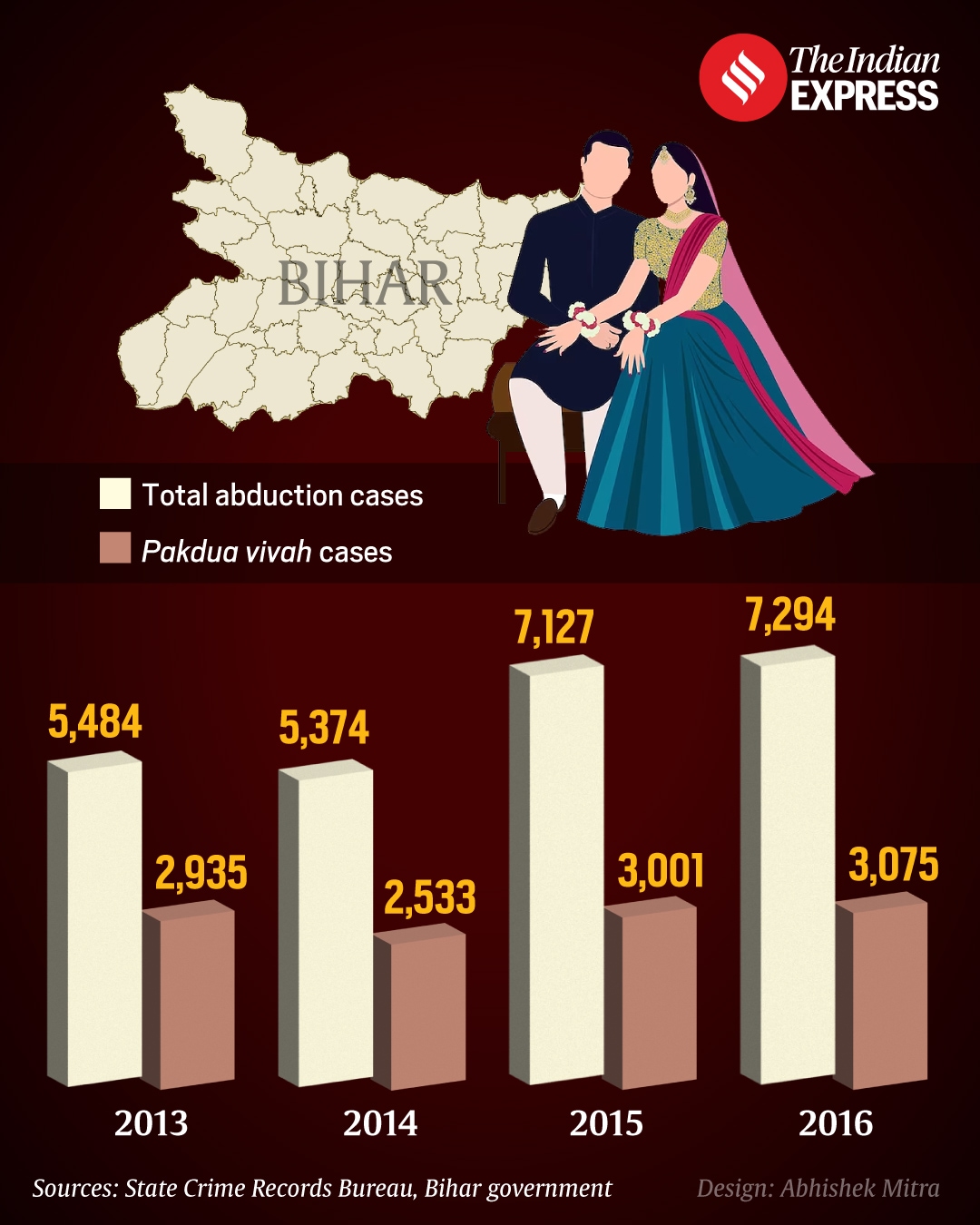

State Crime Records Bureau (SCRB) data states that 2,695 kidnappings for marriages were reported in 2020, while the figure for 2019 was 4,498. Abduction figures released by the Bihar government earlier this year revealed that 40 per cent of such cases between 2013 and 2020 were pakdua vivahs. A senior Bihar Police officer cautioned, “The data has to be read carefully. Even cases of elopement are put under the pakdua vivah category.”

State Crime Records Bureau (SCRB) data states that 2,695 kidnappings for marriages were reported in 2020, while the figure for 2019 was 4,498.

State Crime Records Bureau (SCRB) data states that 2,695 kidnappings for marriages were reported in 2020, while the figure for 2019 was 4,498.

Eligible bachelors from wedding parties were the most common targets in the 1980s, says Shekhar. “Families of girls would get advance information from their acquaintances about the caste of these bachelors. To abduct the right groom, the relatives would rope in a person known to both families. Such was the fear of pakdua vivah between 1970s and 1990s that parents of employed single young men would prohibit them from attending weddings,” he says, adding that boys from the same caste would be targeted to ensure a girl’s social acceptance after marriage.

***

Story continues below this ad

Recalling his own experience, Shekhar says, “When I told the men that I will not get married without my parents’ consent, they threatened to kill me. The whole time, I kept looking for that traitor Anirudh. By 1 am, I gave up. I was bawling and my hands were trembling as I put on a yellow dhoti.”

The couple has five children. (Express photo by Santosh Singh)

The couple has five children. (Express photo by Santosh Singh)

The marriage came as a shock to his 13-year-old bride, Baby Choudhary, too. Since her parents lived in a much smaller village, Baby was sent to live at the house of her maternal uncle Niranjan Choudhary, also a bank clerk, in Shashan village. Her father Upendra Narayan Jha was a clerk in a Katihar-based bank.

Baby says she was unaware of her impending nuptials till the eve of the ceremony. “I was loitering around with friends till late evening (on April 19, 1983), when some elderly women handed me a pair of salwar-kameez and informed me that I was getting married in a few hours. I cried before giving in. Most girls I knew got married in their teens then,” says Baby.

Pakdua vivah or forced marriages at gunpoint were not unusual in Bihar, especially in Munger, Khagaria and Begusarai districts in the 1980s and 1990s.

Pakdua vivah or forced marriages at gunpoint were not unusual in Bihar, especially in Munger, Khagaria and Begusarai districts in the 1980s and 1990s.

Shekhar chimes in, “I was forced to partake in all the marriage rituals. Though there was no band-baaja, the women sang and danced as if it was a consensual match. Some women wondered, in loud whispers, if Baby would be accepted after her marriage. The men were confident that everything would be fine with time.”

Story continues below this ad

After the “marriage”, Shekhar was offered some sweets and sent to his bride’s room. Baby recalls, “He came into the room and just lay on the bed. He did not talk to me at all. He just kept staring at the ceiling. Over the next few days, I would go off to sleep before his arrival and leave the room at dawn.”

Four days later, 150 people from Shekhar’s village came to Shashan to secure his “release”. He says, “There was a heated exchange of words, but village elders prevented a clash saying they were now relatives. Baby’s departure was never discussed since the marriage itself was yet to be accepted.”

At the time of Shekhar’s marriage, his father, Parmanand Choudhary, was a well-off farmer with 8 bighas of land and a pucca house. Shekhar, who had hopes of landing a government job after graduation, says, “I would keep replaying the events of April 19, 1983, in my mind. I was a good student before my marriage, but I barely passed my graduation exams. I hardly thought about Baby while we were apart,” says Shekhar, who went on to become the Padhbhada panchayat mukhiya in 2006.

Eligible bachelors from wedding parties were the most common targets in the 1980s, says Shekhar. (Special arrangement)

Eligible bachelors from wedding parties were the most common targets in the 1980s, says Shekhar. (Special arrangement)

Upendra Jha himself was in the dark about his daughter’s marriage. In fact, he came to know about it only a day later. Baby’s mother too did not dare challenge the decision taken by the head of her joint family.

Story continues below this ad

In those days, the grandfather or the eldest uncle would fix the marriages of all the girls in the family with or without their parents’ consent. In Baby’s case too, her uncle took the decision since she came from a family with extremely modest means and a pakdua vivah would ensure there was no exchange of dowry.

To protect his teenager from gossip after her marriage, Jha moved her to his paternal village near Tarapur. Her schooling was disrupted since she stayed indoors all the time to avoid people. For nearly a year after the marriage, there was no communication between the two families.

Around mid-1984, Baby’s uncle approached Shekhar’s father. His maternal grandfather, Bhola Nath Mishra of Bhagalpur’s Pirpaiti, ended up playing the key mediator. “He (Bhola Nath) tried to reason with me saying that she (Baby) was the daughter of a brahmin and that they married just once. He asked me who would marry her if I deserted her?” says Shekhar.

Though his father was forced to oblige his doughty father-in-law, Shekhar stood his ground. “I refused to accompany my grandfather and father for the gauna ceremony (a ritual marking a bride’s departure to her marital house),” he says.

Story continues below this ad

Baby continues, “When I came to his house, I realised that Shekhar was still upset. Though we shared a room, we didn’t speak to each other until months later. Even then, it was limited to monosyllables.”

She describes her marriage as a journey — from forced marriage to abandonment, followed by laboured acceptance that eventually blossomed into love and respect. “I would keep making him realise that I was too young to be a party to his kidnapping. His behaviour towards me softened eventually. By 1986, we fell in love,” says Baby.

The couple went on to have five children — daughter Shalu in 1990, followed by son Subham, daughter Aadya, son Rishav and daughter Ruchi. Besides becoming a wife and mother, Baby went on to become the mukhiya of Padbhada panchayat thrice. A former panchayat mukhiya himself, Shekhar is now an active member of Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas). The couple carry a considerable clout in Padbhada.

Stating that he was against forced marriages, Shekhar says, “I could not have prayed for a better life partner. Her relatives made a mistake, but I was lucky to get a good wife. Not everyone is as lucky as me.”

Chandra Shekhar Choudhary was 18, while Baby Choudhary was just 13 years old at the time of their pakdua vivah or forced marriages at gunpoint in April 1983. (Express photo by Santosh Singh)

Chandra Shekhar Choudhary was 18, while Baby Choudhary was just 13 years old at the time of their pakdua vivah or forced marriages at gunpoint in April 1983. (Express photo by Santosh Singh) State Crime Records Bureau (SCRB) data states that 2,695 kidnappings for marriages were reported in 2020, while the figure for 2019 was 4,498.

State Crime Records Bureau (SCRB) data states that 2,695 kidnappings for marriages were reported in 2020, while the figure for 2019 was 4,498. The couple has five children. (Express photo by Santosh Singh)

The couple has five children. (Express photo by Santosh Singh) Pakdua vivah or forced marriages at gunpoint were not unusual in Bihar, especially in Munger, Khagaria and Begusarai districts in the 1980s and 1990s.

Pakdua vivah or forced marriages at gunpoint were not unusual in Bihar, especially in Munger, Khagaria and Begusarai districts in the 1980s and 1990s. Eligible bachelors from wedding parties were the most common targets in the 1980s, says Shekhar. (Special arrangement)

Eligible bachelors from wedding parties were the most common targets in the 1980s, says Shekhar. (Special arrangement)