Vikas Has Missed the Bus

As the promise of equality enshrined in the Constitution continues to elude us, Shrilal Shukla’s novel reminds us why Indian democracy is often the rule of people of powerful castes and not of the law.

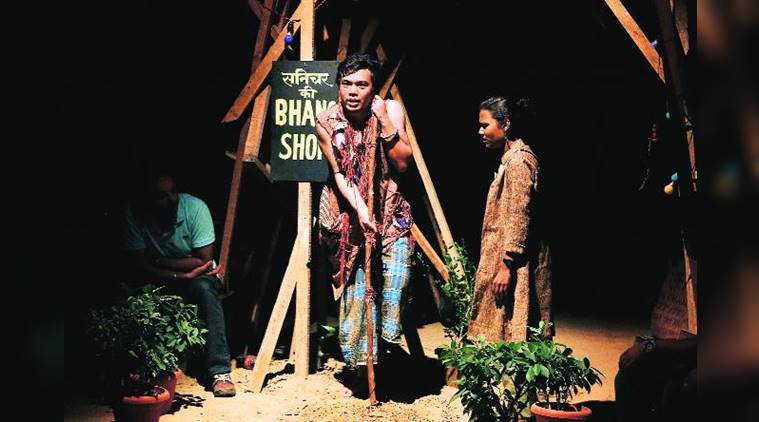

A land like no other: Scenes from a production of Raag Darbari at the National School of Drama that was staged in June this year. The production by first-year students was directed by Amitesh Grover. (Photo Courtesy: National School of Drama)

A land like no other: Scenes from a production of Raag Darbari at the National School of Drama that was staged in June this year. The production by first-year students was directed by Amitesh Grover. (Photo Courtesy: National School of Drama)

Shrilal Shukla’s novel Raag Darbari is celebrating its 50th year of publication this year. It is interesting to know that when this novel was first published by reputed Hindi publisher Rajkamal Prakashan, it was rejected outright by almost all Hindi critics. At a recent function organised by Rajkamal Prakashan to celebrate its 50th year, scholar Pushpesh Pant mentioned how Shripat Rai, writer and editor of the Hindi literary journal Kahani, and the son of iconic writer Munshi Premchand, wrote about the novel in his notes as the “worst kind of storytelling with no central vision (ghatiya kissagoi evam kendriya manisha ka abhaav).” Another critic dismissed it as a novel that was “destined to be not read.”

Paradoxically, it gained instant popularity, going on to win the prestigious Sahitya Akademi Award in 1969, a year after its publication. Over the last 50 years, that popularity has not waned. Generations of readers have loved it and continue to connect with it. This year, the publisher has also come up with its 40th paperback edition. Evidently, the novel has not lost its leadership. In fact, in this age of social media, it has reinvented itself. There are more Twitter handles in its name and that of its characters than any other Hindi book, and, of course, Facebook followers, too. Between social scientists who use it like a case study of rural India and literary critics who revel in its iconic satire, it has redrawn boundaries and continues to resonate with readers.

Another scene from a production of Raag Darbari at the National School of Drama that was staged in June this year. (Photo Courtesy: National School of Drama)

Another scene from a production of Raag Darbari at the National School of Drama that was staged in June this year. (Photo Courtesy: National School of Drama)

The question, of course, remains: what is that element in Raag Darbari that connects it with generations of north Indian readers? Is it the storytelling or the story? Based on a small village — Shivpalganj — situated on the outskirts of a town, it’s a satirical story, but it is also rooted in a culture of unique criticism. It is the first modern Hindi novel which questions the idea of Indian democracy. Shivpalganj has a panchayat, a cooperative society and a college but nothing is as functional as it should be. Vaidji, Badri Pahalwan, Ruppan Baboo, Shanichar, Jognath, Langad are literary tropes who showcase how Indian democracy is far from being of the people, by the people, for the people — the basic premise of democracy. Rather, democracy is in cahoots with feudalism and casteism, often dictating the way society functions. This division of society along casteist lines is deeply entrenched in the country — Indian democracy is the rule of people belonging to powerful castes and not the rule of law, something that Raag Darbari showcases brilliantly. There is Rangnath, the narrator of this novel, who comes to Shivpalganj from a nearby town, and chooses to remain a mere spectator. He is the representative of the New-Age, educated middle class, who observes things from the sidelines, never intervening, never calling or working for change. Raag Darbari was the first Hindi novel to showcase this moral inertia and the hopelessness embedded in Indian democracy. The novel makes a mockery of this — its rich vein of satire says everything about democracy even when it says nothing at all.

Book cover of Raag Darbari.

Book cover of Raag Darbari.

At that time, this was a completely new form of storytelling. It eschewed ideology and vision — considered the most important parameters of fiction writing in contemporary vernacular language. The unwritten code of writing precluded a message of hope that novels were supposed to evoke about the future. Raag Darbari offered none of it. It did not offer ideological conflicts or political alternatives to improve Indian society either. Reminiscent of George Orwell’s works — in particular his allegorical novel Animal Farm (1945) and dystopian novel 1984 (1949) — Raag Darbari could well be Animal Farm written in the narrative form of 1984 for a Hindi readership. After all, the future it foreshadows is a reflection of the past — Shivpalganj, like India, hasn’t changed much in a span of 50 years.

Panchayati Raj has been implemented successfully in Indian villages, but power still lies with its “upper” caste people. Casteism is still at work behind India’s democratic set-up; religion has become a major political tool. The whole of north India has become Shivpalganj, except it does reflect a modicum of change. In Raag Darbari’s Shivpalganj, nobody left the village because they all loved it. But now, people of every Shivpalganj in the country are shifting to the cities because the boon of development has failed to reach them. Raag Darbari’s allegorical story connects strongly with this new India — the displaced India where people are leaving their homes for their own good.

This idea of India as a dystopia that Shukla envisioned 50 years ago is, sadly, still relevant. Every other politician talks about development (vikas) but there is hardly any vikas in Shivpalganj. No wonder, Raag Darbari still feels so contemporary.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05