The Squelch and the Mulch of Rain: Author Sumana Roy on how the sounds of the world change when it rains

The rains force us to become something more than ourselves, like it is the nature of water to spread and increase its occupation.

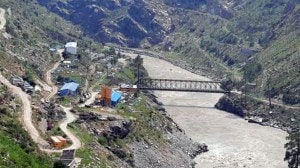

The Himalayas with turbans of clouds on their heads, the mountains are watching them too. (Photo: PTI)

The Himalayas with turbans of clouds on their heads, the mountains are watching them too. (Photo: PTI)

Brishti pawrey ekhaney baro mash

Ekhaney megh gabhir mawto chawrey

When it rains like this, these lines from the Bengali poet Shakti Chattopadhyay come to me. They don’t really come to me. Here it rains all through the year, the clouds graze like cows here… These are Chattopadhyay’s words. And though I know that it doesn’t rain for twelve months – baro maash – in my small town at the foothills of the eastern Himalayas, I also recognise its poetic truth. When it rains like this, forgetfulness sets in – all other seasons disappear, as if merely following its basic function, of washing away.

When it rains like this, everything turns into a container for the rains – walls swell up with water blisters, doors refuse to shut from water retention, streets ooze water like pus, clothes refuse to dry, as if asking for leave from work, from covering our bodies; the water, made more viscous by it, seeping out of tree trunks, the drops that fall off the tips of leaves, as if leaking from them, as if they were theirs, the wind which sheds water droplets every now and then as if it were its rheum…

When it rains like this, incessantly, shamelessly, the world turns into hair, long hair from whose ends water drops all day, seeping into everything, making the world feel like it needs to change its clothes. When it rains like this, the sounds of the world change. We speak louder, the rain turns us into singers and it becomes an accompanist. The rains force us to become something more than ourselves, like it is the nature of water to spread, to increase its occupation, so with rain, and with the clouds that carry them.

Entering a forest in June, where everything has been turned into a sponge oozing water that it can no longer retain – leaves and bark, soil and the sky, leeches that water provokes into their hunger for blood, its relative – I find the mountains turned blue by rain. Not the lifelessness of livor mortis or a deep bruise, but the blue that idol makers paint on the body of Shiva. The clouds rest on them, and, in doing so, sometimes become one with them, the way sleep becomes one with the body. But there is separation too – the way the sleeping body is separate from the bed. I am, perhaps, thinking of sleep because of the soundless character of these clouds. Inside the forest, though, are species of sounds that remind me why the xylophone is called the jaltaranga in Bangla and Hindi.

Above me the clouds, around me, covering the earth are Colocasia leaves, both in abundance, looking abandoned, almost a visual echo. They are choking and bursting with water – both, waiting to let go of it. The fleshiness of the stems and leaves – when they break, not life but water rushes out of them. It has its own music, a short poem sure, but one that cannot be repeated, for such is the nature of such music – this is not riyaz, not practice, for it can be made only once. Does it bear any resemblance to the sound of ‘glut’ or ‘gulp’?

I think of the words that reveal excess, how they begin with ‘g’: greed and gluttony. And I notice how I don’t hear these words when a drop of rain falls on a leaf, and, later, falls off its tip. This intimacy, soft and silent, is the sonic opposite of the grr grr – garjan in Bangla – that attends thunder and lightning. Ghanan ghanan ghir ghir aaye badra/Ghane ghan ghor kaare chhaye badra.

Drying, the loss of water, does not arouse comparable feelings. Drying is soundless, as is mist. The sonic register of mist is even lower than a whisper – notice how the ‘t’ is almost inaudible. That is why we can hear a ‘missed call’ but not a ‘mist call’. For the mist does not call, cannot call.

For when we go to another word beginning with ‘m’ that holds water, we hear it like one hears potato wafers breaking inside a human mouth – ‘mulch’, it must reduce evaporation and hence that sound, the relationship with water in the background. It’s the ‘ch’ sound ending that provokes this intuition, for inside our ears is a word that is holding water inside it, water that is waiting to be released as soon as we step on it. ‘Squelch’. Squelch. The sound of mud in water, as if it has its own footsteps. Squelch. Ch. Cha, chai – tea, that thing that’s dissolved in water, lost its unnecessary prefixes and become that water, the ‘ch’ that was waiting to be released. A little more water and ‘ch’ becomes ‘chh’ – ‘chhetano’, ‘chhiti’, water wants to spread, for that is its nature, ‘Chhai chhap chhai chhapak chhai/Paaniyo pe chhinte udaati hui ladki …’

I listen to the response of the living to water: the sound of young leaves, fish coming to the shore, the tin roofs in the rain, waterlogged fields, cow standing in the middle of the road. The leaves let the water go, the fish come towards the shore where there is less water, the tin roof directs them to a more stable habitat, the cow doesn’t know what to do with it, the fields keep it inside their chest. I see all this from under an umbrella, as I walk in the drizzle. Not far away, to my right, are the Himalayas – turbans of clouds on their heads, the mountains are watching them too. This difference in the way one retains water or lets it go, and for how long, applies to humans as much to landscapes, plants and animals.

How irregularly the sun rests on the mountains, favouring one for some time, ignoring another part, and reversing these patterns again. Then there is the other side – mountains have windward and leeward sides, one that gets the rain and another that doesn’t. I find myself thinking of the cheeks, those pieces of flesh raised by cheekbones, the tiny hillocks on the face that receive our tears, and the back of the head, the leeward side. What does that imply for the landscape of the face and its ability to accommodate emotions?

Everything grows in the rains, everything grows and growls.

But tears? Why do they have no sound?

Roy, a poet and writer, is associate professor at Ashoka University. Views are personal

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05