Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

Devotees take the Goddess across the Hoogly, where she will be worshipped at the local barowari puja. (Credit: Partha Paul)

Devotees take the Goddess across the Hoogly, where she will be worshipped at the local barowari puja. (Credit: Partha Paul)What 12 men did three centuries ago to make Durga Puja accessible to all

On the way to Guptipara, a small town in Hooghly district, some three hours away from Kolkata, the white kash phool (flower) (Saccharum spontaneum) are in full bloom, signalling that the autumn festival of Durga Puja is just around the corner. Among the oldest towns in Bengal, Guptipara, is best known for its Vaishnava terracotta temples and gupo sandesh, one in the many kinds of mishti found in the state. But what is less well-known is that this town also gave the world Durga Puja in its most well-known form: the barowari puja or the community Durga Puja.

What makes the Durga Pujas of rural and suburban Bengal different from their Kolkata counterparts

Serampore Rajbari Puja (Credit: Debojyoti Goswami)

Serampore Rajbari Puja (Credit: Debojyoti Goswami)

Every July, the Goswami household in Serampore Rajbari (Serampore royal-family home) comes alive in preparation for the most important festival of the year. Located about 30 km north of Kolkata across the Hooghly, Serampore is well known as the erstwhile Danish town of Bengal. Hyderabad-based businessman Debojyoti Goswami, 36, the ninth generation of the family, says that no matter where he is, Durga Puja means homecoming. Along with his cousins, Goswami is in charge of putting together the 328-year old Puja that was started by Lakshman Goswami, a staunch follower of the Vaishnav saint Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, and that differs, in subtle ways, from the pujas in Kolkata. After all, it carries with it the whiff of a suburban character missing from the urban landscape of Kolkata.

How our consumption of Durga Puja has changed over the years

An idol by Aloke Sen (Courtesy: Niladri Chatterjee)

An idol by Aloke Sen (Courtesy: Niladri Chatterjee)

Long before Unesco was thinking of Durga Puja as part of humanity’s “intangible cultural heritage”, Niladri Chatterjee was collecting very tangible artefacts of Durga Pujas past. He has a black-and-white glossy print from 1979 of a Durga image from Tarun Sporting Club — a fairly traditional Goddess on a rearing lion, spearing Mahisasura while emaciated men in dhotis look on from behind bars. At the corner is the artist’s name — Aloke Sen.

Tucked away in the heart of Kolkata’s Cossipore area lies the city’s oldest Durga Temple

Kashiswar Roy Chowdhuri with daughter Rituparna and son Chandraroop at Chitteswari Durga temple. (Express photo by Shashi Ghosh)

Kashiswar Roy Chowdhuri with daughter Rituparna and son Chandraroop at Chitteswari Durga temple. (Express photo by Shashi Ghosh)

The road leading to Kolkata’s oldest temple has a distraction. The Sarba Mangala Temple, dedicated to a different form of the sublime goddess, is a few paces ahead of the Chitteswari Durga temple. It’s buzzing with activity, its dome is clearly visible from a distance and it can easily be mistaken for being the oldest temple of the area. Chitteswari Durga temple, built in 1610, in contrast, seems more like a residential quarter. It’s quieter, almost withdrawn from the busy stretch of road that also houses, most appropriately, one of India’s oldest weapon factories — Cossipore Gun and Shell factory. “This is in keeping with the history of the goddess here. For centuries, she remained hidden in the jungles before devotees found her again. When she calls out to you, you come here,” says Kashiswar Roy Chowdhuri, the current supervisor of the temple.

Catching up with the mega fauna in Africa on the translocation of the cheetahs

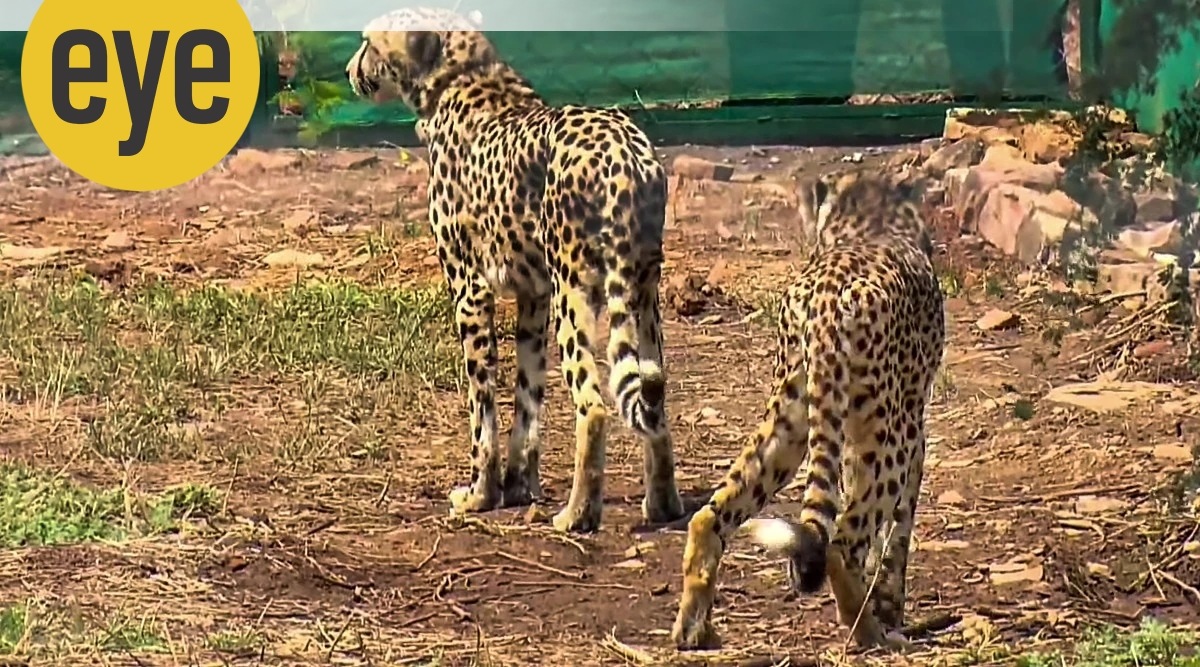

A new home in India for the Namibian cheetahs. (PTI Photo)

A new home in India for the Namibian cheetahs. (PTI Photo)

Now that the cheetahs have arrived and been released in Kuno, how have some of Africa’s other big mammals taken to the development? Down in Jungleland (DiJ) interviews a select few of Africa’s mega fauna and some of our own local fauna.

‘The Durga Puja ceased to be purely religious in its urban form a very long time ago’: Historian Tapati Guha-Thakurta

Tapati Guha-Thakurta with artist Partha Dasgupta, State Bank Park Puja, Thakurpukur, 2020 (Courtesy Tapati Guha-Thakurta)

Tapati Guha-Thakurta with artist Partha Dasgupta, State Bank Park Puja, Thakurpukur, 2020 (Courtesy Tapati Guha-Thakurta)

In her 2015 book, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (Primus), historian Tapati Guha-Thakurta traces the evolution of the traditional pujo to its modern form, that moves beyond religious aspects of Bengal’s most well-known festival to talk about its creative, cultural and social aspects. Little surprise then that Guha-Thakurta was chosen by the Ministry of Culture to put together a dossier highlighting the spirit of the festival for its inclusion in Unesco’s Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Who are the social leaders from Maharashtra holding up Mahatma Gandhi’s legacy

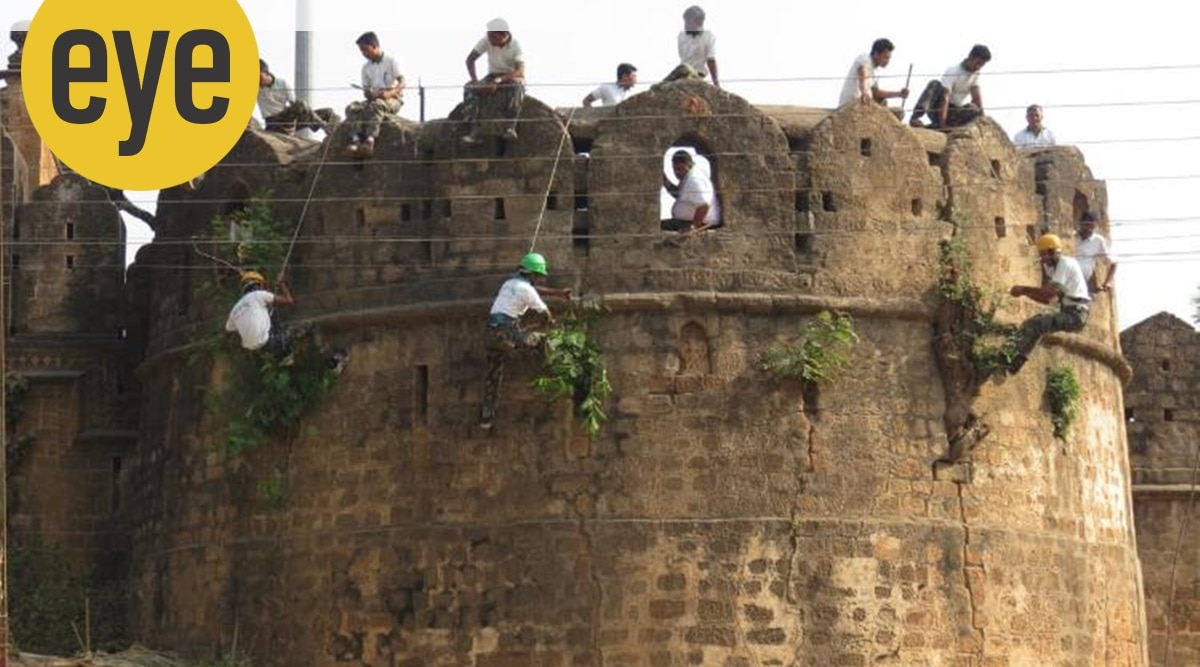

Bandhu Dhotre and his team cleaning the 500-year-old Chandrapur fort which got a mention in the PM’s Mann ki Baat (Photo courtesy: Ashutosh Salil and Barkha Mathur)

Bandhu Dhotre and his team cleaning the 500-year-old Chandrapur fort which got a mention in the PM’s Mann ki Baat (Photo courtesy: Ashutosh Salil and Barkha Mathur)

What is selfless to one is selfish to another. Few can relate to that predicament more than the woman who remains homebound while her husband is out in the world, bringing home the bread and accruing social capital. For instance, it afflicts Yojana, the wife of Bandu Dhotre, 43, a prominent wildlife activist based in Chandrapur, Maharashtra, every day of her life. They were young when he wooed her. Bandu’s idealism and passion for social service inspired her. But now, years into their marriage, she recognises what she signed up for: a lifetime of sacrifice, struggle and patience, the last of which is tested whenever she has to answer to her children why their father is a celebrated figure in school but doesn’t have money to buy them ice cream.