Oscar-winning Eva Orner on directing a documentary on the founder of Bikram Yoga in a pre MeToo world

Inhale, Exhale: Orner’s documentary Bikram: Yogi, Guru, Predator, currently streaming on Netflix, made over a period of three years, combines archival footage, interviews of Choudhury’s students and practitioners of the form.

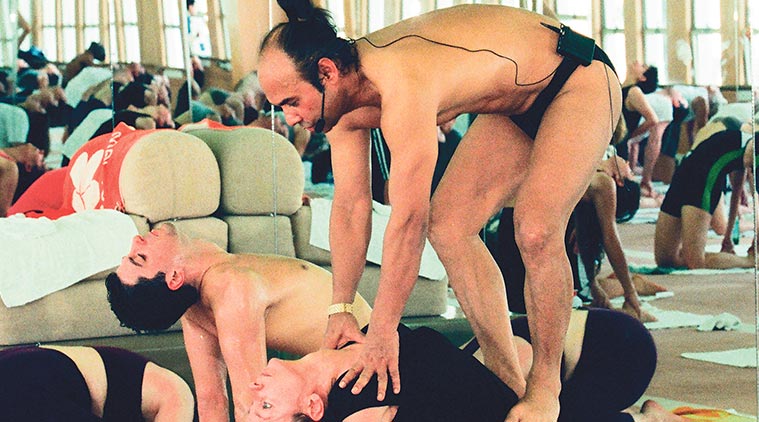

Chronicler of things untold: A film still from Bikram: Yogi, Guru, Predator. (Source: IMDB)

Chronicler of things untold: A film still from Bikram: Yogi, Guru, Predator. (Source: IMDB)

In a span of over 1 hour 20 minutes, director Eva Orner takes a deep dive into the world of Bikram Yoga, a form of hot yoga, and its founder Bikram Choudhury. He and his style of yoga were popular in the late 1970s and his charmed life was nowhere near fading until allegations of sexual abuse and harassment surfaced against him in the early 2010s.

Orner’s documentary Bikram: Yogi, Guru, Predator, currently streaming on Netflix, made over a period of three years, combines archival footage, interviews of Choudhury’s students and practitioners of the form. Orner, 50, who produced the Oscar-winning film Taxi to the Dark Side (2007), which looks at “the Bush administrations torture policies post 9/11”, talks about Choudhury, the #MeToo movement and growing up in Australia in an email interview from Los Angeles, US. Excerpts:

Eva Orner. (Source: IMDB)

Eva Orner. (Source: IMDB)

How did Bikram: Yogi, Guru, Predator come into being?

A development executive from a UK-based production company first approached me about doing a film about Bikram Choudhury. She had seen my last film (Chasing Asylum, 2016) at the BFI London Film Festival and reached out. She had been an avid Bikram yoga practitioner and had moved to a non-Bikram hot yoga studio in the wake of the allegations. I knew a little about Bikram. I did some initial research and knew pretty quickly there was a film to be made. I think what got me so interested is that Bikram was a man who had gotten away with it. And this was pre-#MeToo. After #MeToo occurred — during the production period — with it came the outing and reckoning of so many powerful men. The fact that Bikram got away with his crimes was even more relevant and chilling.

Have you attended a Bikram Yoga class?

I did a number of Bikram and hot yoga classes as part of my research and to meet the community. I also needed to observe the poses, to work out how to film them most effectively. While I appreciate the poses and the fact that it has helped a lot of people, I will not be incorporating them into my exercise routine.

His story looks appealing — an Indian who comes to Beverly Hills, US, and sets up this empire, replete with Bentleys and celebrities like George Clooney.

Bikram’s story is a classic American Dream story. He arrived as an outsider with very little, became a huge success and accumulated great wealth. I think that story is very appealing to people around the world. The only problem is, along the way, Bikram told many lies, committed crimes and is now a fugitive. So, rather than being inspirational, it is a chilling story about greed, celebrity and fame.

After Wild Wild Country (2018) about the Osho cult, comes your film about Choudhury’s cult. Why do you think these practices have such a draw?

I’m no expert, but all I can say is that there are definitely people who are seekers, drawn to things like Bikram yoga for many reasons: injury, weight loss, addiction, wanting to be part of a community.

Was it tough for women to open up about their experiences?

I was a stranger and not from the Bikram world, so I did a bunch of Bikram and hot yoga classes to familiarise myself and understand what made the yoga appealing. Most people in the film were somewhat guarded when we first approached them. They warmed up to me after a few meetings. In some cases, I had them watch my previous work which gave them confidence in me. Some of Bikram’s staunch supporters either didn’t respond to my emails/calls or declined to participate. Some with ongoing cases were unable to talk, while others backed out at the last minute. Participating can either be cathartic or open up old wounds.

What has been your takeaway?

The women were brave. They spoke out about Bikram in a pre-#Metoo world. They had no support, were vilified, lost their livelihood, friends, community. I think, and hope we are seeing a (social) shift, where women are believed. Where laws are being changed to protect women. And where men start speaking out in support of women. There has been too much complicity for too long.

Did you always want to become a filmmaker, a documentary one at that?

I’ve always been very interested in human rights, journalism and telling stories of the under-represented. It comes from my family story. My Jewish parents were born in 1937 in Poland. Three of my grandparents perished in the Holocaust. My parents were lucky enough to come to Australia as immigrants and as a result, I had a very fortunate, happy upbringing in Melbourne and a solid education which informs what I do. I knew I wanted to make films since an early age.

What has been your earliest cinematic influence?

A film I always go back to is an Australian classic film, The Year My Voice Broke (1987). I saw it in my final weeks of high school and it really spoke to me about childhood, isolation and going against the grain.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05