Writer Anand’s records point to many ways in which authoritarianism can manifest itself

For the Malayalam writer, the Emergency has not been a moment frozen in history. It is a sentiment or a tendency that needs to be guarded against and called out.

Malayalam writer Anand. (Photo credit: Tashi Tobgyal)

Malayalam writer Anand. (Photo credit: Tashi Tobgyal)Close to midnight on June 25, 1975, President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signed the Emergency proclamation that marked the suspension of parliamentary democracy in India. Two hours later, the government disconnected power supply to newspaper offices in Delhi. Then, the arrests began. The main voices of the Opposition, among them freedom fighter and Gandhian, Jayaprakash Narayan (JP), who had addressed a mammoth rally against the Indira Gandhi government hours earlier in the national capital, was detained. So were scores of prominent Opposition leaders, including former Deputy Prime Minister of India, Morarji Desai, Congress dissenters such as Chandra Shekhar and Mohan Dharia, Socialist Party chairman George Fernandes, Jan Sangh leaders such as Nanaji Deshmukh, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and L K Advani, CPI-M leaders including AK Gopalan and Jyotirmoy Basu. Thus began the long night that lasted 21 months, during which fundamental rights guaranteed under Article 19 of the Constitution, including the right to free speech and expression, the right to assemble peacefully and without arms, the right to unionise, and the right to move courts to enforce civil rights, were suspended. Over the next few months, newspapers and magazines would be heavily censored and dissenters — politicians, public intellectuals, bureaucrats, journalists — would be arrested. A cult was built around the prime minister and a massive propaganda launched by the government to claim that the country was never in better economic health. The government demanded a committed judiciary and bureaucracy and the foreign hand was invoked to discredit criticism. Dissenters were branded as anti-nationals. Satire and humour were banned as courtiers sang in praise of the prime minister. The Emergency was a bloodless coup by the incumbent government, which subverted the Constitution and the institutions that protected the rights of citizens. Fear reigned until Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, unexpectedly, called for elections on January 18, 1977. By March 20, Gandhi and most of her cabinet colleagues had been defeated. The Internal Emergency was formally lifted on March 21.

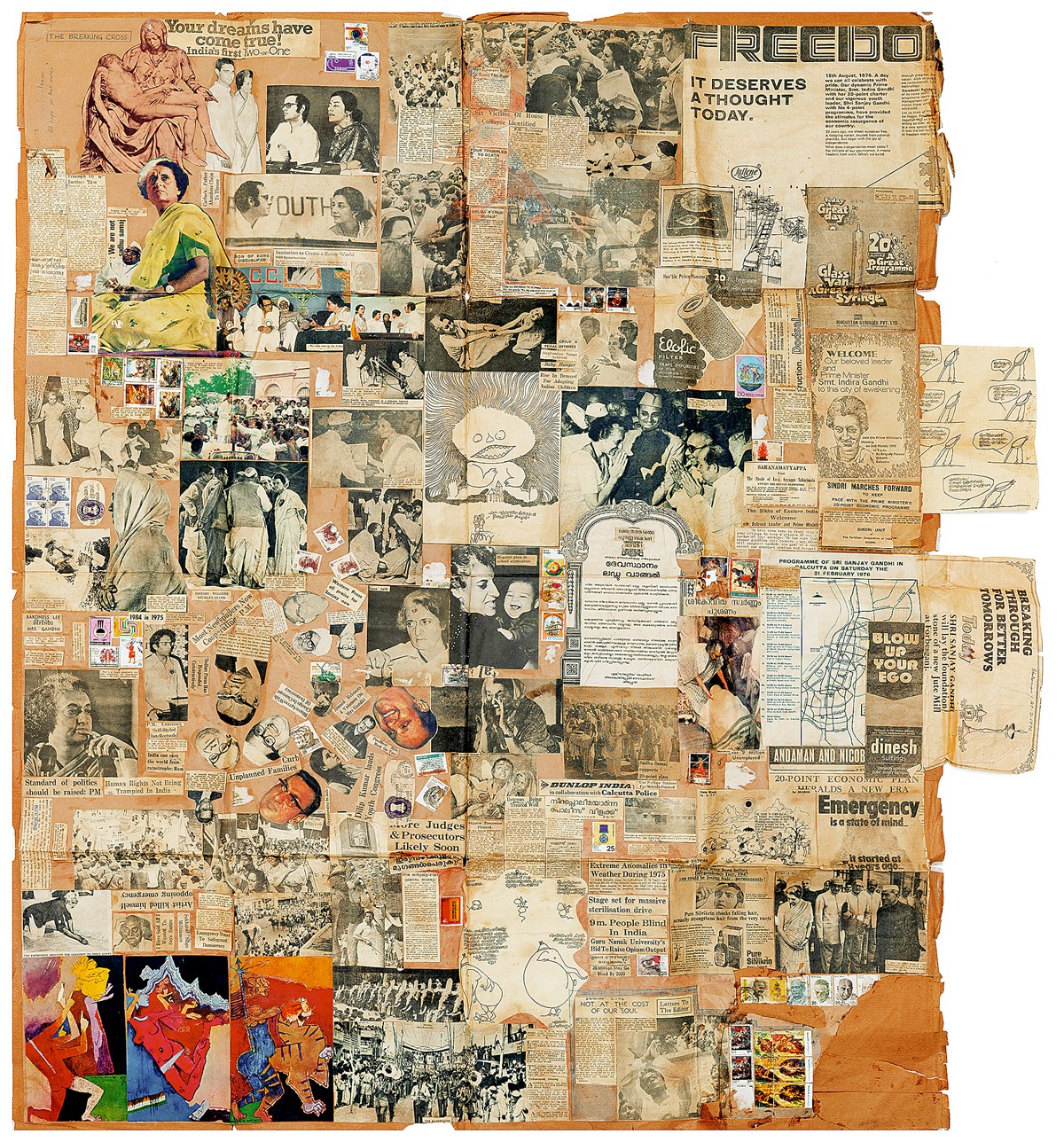

A more interesting work from this phase is a collage — The Breaking Cross — that he prepared in 1977-78, using material from newspapers, journals, stamps etc.

A more interesting work from this phase is a collage — The Breaking Cross — that he prepared in 1977-78, using material from newspapers, journals, stamps etc.

All through these 21 months, Anand (P Satchidanandan), an engineer who had caught the attention of the Malayalam literary world with his debut novel, Aalkoottam (1970, Crowd), and the novella, Maranacertificate (1974, Death Certificate), was in Farakka, the north Bengal town overlooking the newly independent Bangladesh. He heard the declaration of Emergency on his radio. The only other source of news besides radio was The Statesman, which arrived a day late in Farakka from Calcutta. On the day after the declaration of the Emergency, the newspaper had its front page blank and “censored” written in big letters. Anand, now 87, remembers. Life in the township of Farakka was normal to the extent that it seemed banal in its dreary routine. News of gloom and doom arrived by post, in magazines and letters disfigured by the censor’s ink. Anand was working on his second novel, Abhayarthikal (Refugees), a meditation on the human condition, influenced by the tragedy and trauma he had witnessed in the wake of the 1971 war at Farakka. The short stories he wrote during the Emergency — “Abhayarthikal”, “Kuzhi (Pit)”, “Kodumudi (Peak)”, “Badshah Nama” — reveal a writer distraught at the fate of the nation and its citizens. His fiction has since been recognised as among the finest in Malayalam and Anand now is celebrated as a writer and public intellectual in the Malayalam speaking world. However, his work in relation to the Emergency, especially as a memorialist and an archivist, is equally significant. It has resonance even today for it points to the paths authoritarianism takes and how it manifests.

***

Malayalam writer Anand (Photo credit: Tashi Tobgyal)

Malayalam writer Anand (Photo credit: Tashi Tobgyal)

During the years in Farakka — Anand arrived in the town in 1970 after having served in the Army and continued to live there till 1984 — he experimented with multiple media. He wrote fiction and essays and made terracotta sculptures. A more interesting work from this phase is a collage — The Breaking Cross — that he prepared in 1977-78, using material from newspapers, journals, stamps etc. Now a pale yellow crumbling sheet, fraying at its edges, “The Breaking Cross” is a remarkable archive of the Emergency. The news headlines, snapshots of news reports, photographs, slogans, advertisements, and cartoons that crowd the 5ft x 4.5ft collage offer a window to history. In its own ominous way, it reminds us, as an advertisement tagline puts it, the “Emergency is a State of Mind,” not merely an event to be talked about as a thing of the past but a condition that continues to exist in dormancy, prone to manifestation any time and in newer forms. Like Vivan Sundaram’s Emergency drawings, Anand Patwardhan’s film Prisoners of Conscience (1978), the John Oliver Perry edited Voices of Emergency (1983), a collection of poetry written in various Indian languages during the Emergency, My Prison Diary (1979) by JP and testimonial literature from many others, The Breaking Cross exists as a political document that marks a moment in history and offers lessons for our times.

Anand has also created an archive of publicity and propaganda literature that highlighted the claims of 20-point programme, texts of radio broadcasts of Indira Gandhi, doctored statistics that offer a playbook of authoritarianism, the Indian version.

In an introductory note to the The Breaking Cross, Anand writes: “Though it starts with the dismaying lines of Dante, ‘Leave all hope ye that enter’, the end part made of stamps on birds, the last one of a bird flying into the open sky, was supposed to extend some hope”. He adds that “ironically, and ominously too, this portion (depicting hope), was vandalised by some people when the collage was presented at a public exhibition” and has since been missing. In its original form, Anand had also imposed a pencil drawing of his sculpture, “The Breaking Cross”, on the collage. The idea, he says, was that even the cross, the symbol of endurance, can break under extreme conditions.

Next to Dante’s lines is a large visual of Indira and Sanjay Gandhi juxtaposed against text cropped out from an advertisement for a tape-recorder, that reads: “Your dreams have come true. India’s first Two-in-one”. On the top right corner is another ad, this one for vests. Its caption in large point size reads: “Freedom: It deserves a thought today”. The tagline in smaller points read: “15th August, 1976. A day we can all celebrate with pride. Our dynamic Prime Minister, Smt Indira Gandhi with her 20 point charter and our vigorous youth leader, Sri Sanjay Gandhi with his 4-point programme, have provided the stimulus for the economic resurgence of our country”. There are also photographs and quotations from prominent leaders of the time: “Hard work and discipline make the nation great”: Indira Gandhi; “India can save the world from catastrophe”: Jagjivan Ram; “Even today our press freedom is one of the best in the world”: V C Shukla; “Most newspapers now cooperating”: PM.

Then there are headlines in English and Malayalam. One reads: “Emergency meant to safeguard democracy”. Also, “PM criticises self-styled intellectuals”. Another says, “Human Rights Not Being Trampled in India”, juxtaposed against a new report that says the “number of undertrials exceeds the number of convicts by about 16 per cent in jail”. Meanwhile, the PM was also demanding that “Standard of Politics Should be Raised”. A news report mentions a notice put up at a public library in north Calcutta: “On and from 1st January, 1976, newspapers will be found in the fiction section.” The subversive spirit of dissent was captured in tail pieces that appeared in newspapers and magazines, recalls Anand. He scanned The Statesman and The Indian Express, besides the journals that he subscribed, Quest and The Radical Humanist.

Anand’s friend, the celebrated writer and cartoonist OV Vijayan, had stopped drawing in English but was offering cerebral, incisive material to the Malayalam magazine, Kalakaumudi. Vijayan feared that like many other friends of his, he too would be arrested. Vijayan has at least two cartoons in the collage. One of the speech balloons in his cartoon reads: “This is nature’s law. Cowards terrorise the rest”. Like all other material Anand had sourced and used, Mario Miranda’s sharp cartoon also remains relevant today. Here, the leader tells the crowd: “I’ve come to warn you of the threat that could destroy the delicate fabric of our beloved democracy… the danger is from the sea… so keep a look out for the foreign ships.”

In the essay “Political Uses of Photo-Montage”, John Berger explains how (German artist who worked as a graphic propagandist for the German communist press between 1927 and 1937) John Heartfield’s propagandist work qualified as political art. “With his scissors he cuts out events and objects from the scenes to which they belonged. He then arranges them in a new, unexpected, discontinuous scene to make a political point… The peculiar advantage of photo-montage lies in the fact that everything which has been cut out keeps its familiar photographic appearance… But because these things have been shifted, because the natural continuities within which they normally exist have been broken, and because they have now been arranged to transmit an unexpected message, we are made conscious of the arbitrariness of their continuous normal message. Their ideological covering or disguise, which fits them so well when they are in their proper place that it becomes indistinguishable from their appearances, is abruptly revealed for what it is. Appearances themselves are suddenly showing us how they deceive us.” The Breaking Cross achieves the same goal. As is the case with most art produced during unpleasant times, it weaponises humour, irony, satire and sarcasm to reflect on the Emergency. Ironically, humour and satire have rarely featured in Anand’s fiction, before or after the Emergency.

***

Malayalam writer Anand (Photo credit: Tashi Tobgyal)

Malayalam writer Anand (Photo credit: Tashi Tobgyal)

For Anand, the Emergency has not been a moment frozen in history. It is a sentiment or a tendency that needs to be guarded against and called out. In his writings — fiction, non-fiction, short essays to letters to the editor — Anand has not hesitated to call out authoritarian tendencies. His fiction from the 1980s — Marubhoomikal Undakunnathu (Desert Shadows), Vyasa and Vighneshwara, Govardhante Yatrakal (Govardhan’s Travels), Apaharikkappetta Deivangal (Stolen Gods), Jaivamanushyan (The Organic Human), Vettakkaranum Virunnukaranum (Hunter and Guest) — have been shaped by his studies of authoritarianism, of authority and power; in fact, the novel Desert Shadows is a Kafkaesque tale of how authorianism works within institutions of the nation state. He has spared no ideology while calling out illiberal tendencies — communism, Hindutva, Islamism have all come under his lens and indicted — giving him the aura of a public intellectual with a rare integrity. It is this ability to historicise and spot the storm that provokes Anand to add that when authoritarianism is backed by an ideology, it can be more dangerous. The Emergency, he said, was bad, but the forces that have come up in the name of saving democracy pose a formidable new challenge.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05