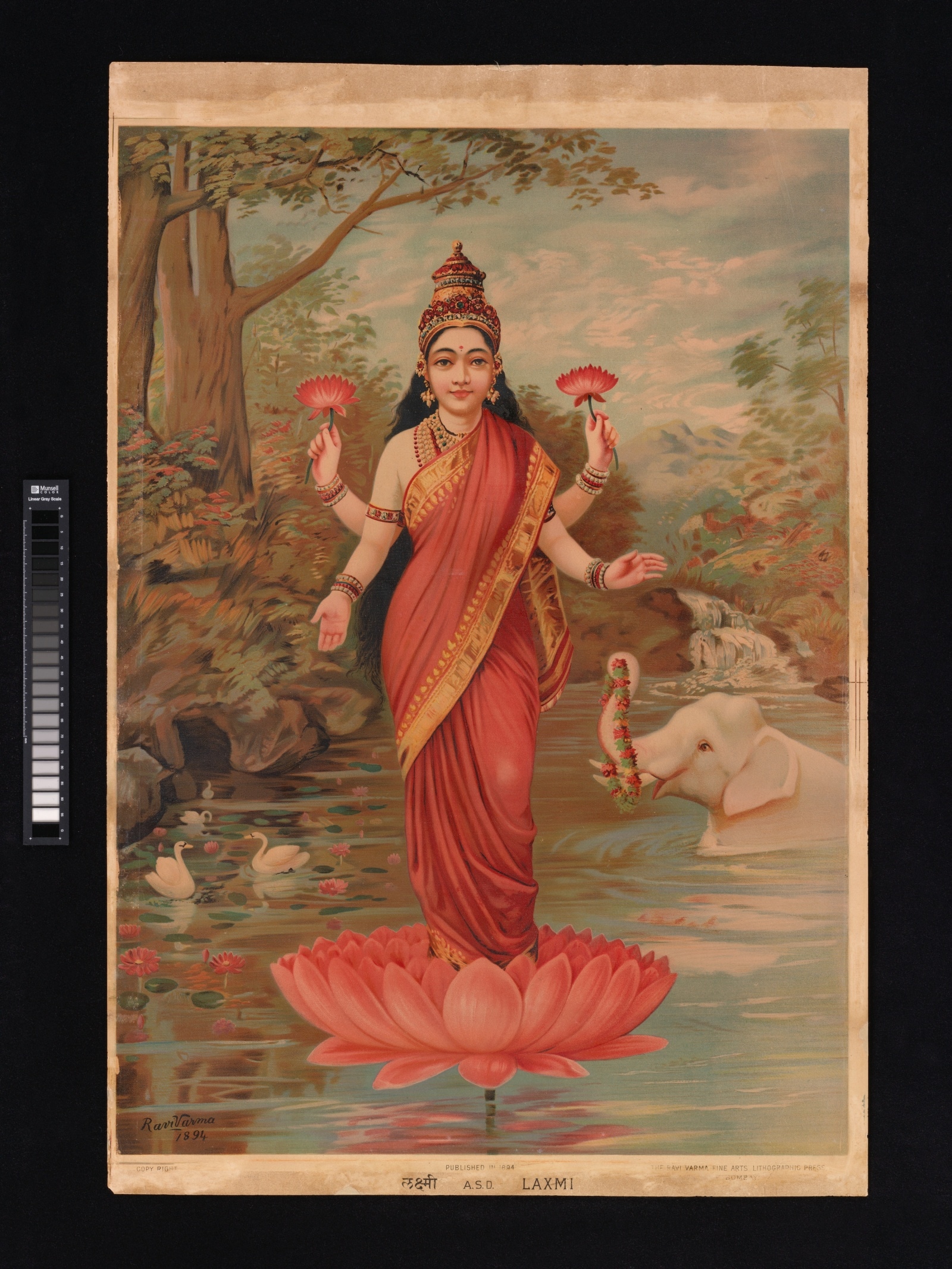

Festive Frames: Raja Ravi Varma’s ‘Lakshmi’ and other visual depictions of Diwali

A look at how art works captured the spirit of the festival of lights

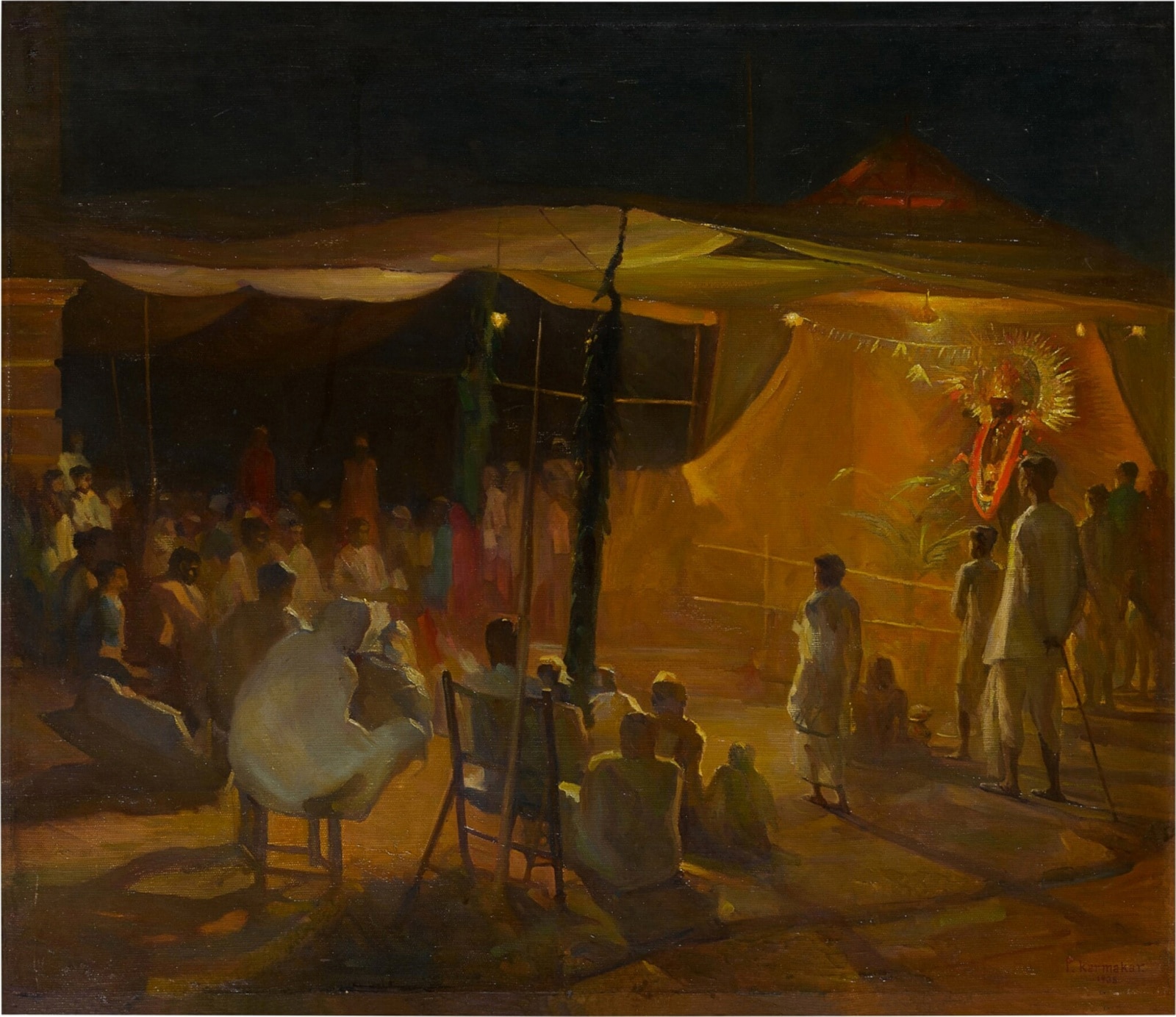

In this scene, painted by Prahalad Karmakar, villagers are seen in a makeshift pandal lit with electrical lights (photo: DAG)

In this scene, painted by Prahalad Karmakar, villagers are seen in a makeshift pandal lit with electrical lights (photo: DAG)Lakshmi, 1894

Raja Ravi Varma

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/78264

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/78264

Merging European academic realism with Indian traditions, artist Raja Ravi Varma is often credited for humanising mythological deities by painting them in more realistic settings that were relatable to the worshippers. His depiction of Lakshmi remains one of the most iconic and enduring images of the goddess of wealth.

Originally painted in oil in the 1890s, it was later widely reproduced in oleographs at his printing press, making it accessible to a wider audience. Dressed in a pink saree with delicate gold border, Lakshmi is portrayed standing on a lotus, which symbolises spiritual awakening and purity. She is flanked by a white elephant, emblematic of royalty and auspiciousness. While one of her four hands is raised in abhaya mudra, offering protection, another is in varada mudra to bestow blessings. Gold coins flow from her palm, signifying wealth and prosperity.

CREDIT: www.metmuseum.org

Medium: Lithograph

Court Ladies Playing With Fireworks

Attributed to Muhammad Afzal (active 1740-1780), Mughal Court

(Artist) Attributed to Muhammad Afzal

(Artist) Attributed to Muhammad Afzal

While the lights and diyas symbolise the triumph of light over darkness and good over evil, the fireworks in Diwali are also meant to be celebratory. Believed to have originated in China and used lavishly during royal events in India by the 16th century, as firecrackers became more accessible they became part of public festivities, particularly Diwali. In History of Fireworks in India between 1400 and 1900, published in the 1950s, historian PK Gode noted, “The use of fireworks in the celebration of Diwali, which is so common in India now, must have come into existence after about 1400 AD, when gunpowder came to be used in Indian warfare.”

Though several miniatures from 15th century onward depict firecrackers being used for festivities, this particular 18th century artwork from the Mughal Court has a group of women playing with phujhadis. Once belonging to art historian Ananda K Coomaraswamy, it is now in the collection of Freer Gallery of Art.

CREDIT: https://asia.si.edu/

Village Kali Puja, 1938

Prahlad Karmakar

In this scene, painted by Karmakar, villagers are seen in a makeshift pandal lit with electrical lights.

In this scene, painted by Karmakar, villagers are seen in a makeshift pandal lit with electrical lights.

Celebrated on the new moon (amavasya) during the Hindu month of Kartik, Kali Puja is held on the night of Diwali in the eastern states of India, when the goddess is worshipped as a destroyer of evil. Temples and homes are decorated with lights and diyas, and the idol of Kali is offered traditionally cooked food, sweets and hibiscus flowers that are seen as a representation of divine energy, fierceness and power.

In this scene, painted by Karmakar, villagers are seen in a makeshift pandal lit with electrical lights. They are gathered around the deity’s idol that is adorned with garlands and gold ornaments. A quintessential depiction of festivities in rural Bengal of the time, the oil on canvas celebrates collective devotion.

CREDIT: DAG

Paradise, 2025

Paresh Maity

A vibrant 45-ft canvas capturing the illuminated ghats of Varanasi during Dev Deepavali, celebrating joy, devotion, and the festival of lights (photo credit: Paresh Maity)

A vibrant 45-ft canvas capturing the illuminated ghats of Varanasi during Dev Deepavali, celebrating joy, devotion, and the festival of lights (photo credit: Paresh Maity)

Held 15 days after Diwali, on the full moon night of Kartik Purnima, Dev Deepavali marks the festival of lights as celebrated by the gods. It commemorates the victory of Lord Shiva over the demons Tripurasura, after which it is believed that the gods descended to the ghats of the Ganga for aarti and to bathe in its sacred waters. As an expression of joy and devotion, the ghats of Varanasi and the river are lit with countless diyas that night.

The scene has been portrayed by Maity in numerous arworks, including this 45-ft canvas. Since he first visited Varanasi in 1984 as an art student, he has returned to the city countless times, also making a particular effort to be there for the festivities of Dev Deepawali. He states, “It’s probably the most magnificent festival I’ve ever witnessed, with billions of diyas illuminating the river, creating a magical atmosphere. The energy, joy and sense of celebration are unbelievable and unmatched. Being on the ghats at the time feels absolutely surreal.”

Diwali celebrations at Kotah, c. 1690

Diwali celebrations at Kotah c. 1690. Felton Bequest, 1980. Image courtesy National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Diwali celebrations at Kotah c. 1690. Felton Bequest, 1980. Image courtesy National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Set in a palace complex with domed arches and corridors, probably in Bundi or Kotah, the richly populated depiction features multiple scenes of ritual grandeur. While the left corner has spectators attending a dance recital, the lower right has people playing instruments in a celebratory procession that also has decorated elephants and horsemen. At the very center is a rectangular chowk lit with flames from several lamps.

A note on the National Gallery of Victoria website, which has the opaque watercolour in its collection, states, “This view of a celebration in a Rajput palace is one of the earliest examples of the genre of tamasha paintings, panoramas describing scenes of court life, that blossomed in the early 18th century… The festivities may represent Diwali, the New Year Festival of Lights devoted to Lakshmi the Goddess of Wealth and Good Fortune. To secure luck for the coming year the Goddess is worshipped at her shrine, and the light from fireworks and oil lamps symbolises the victory of the forces of light over the forces of darkness.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05