Farming the Revolution: director Nishtha Jain’s year with the farmers’ protests

With her documentary Farming the Revolution screened recently at DIFF, director Nishtha Jain talks about the challenges of censorship and funding

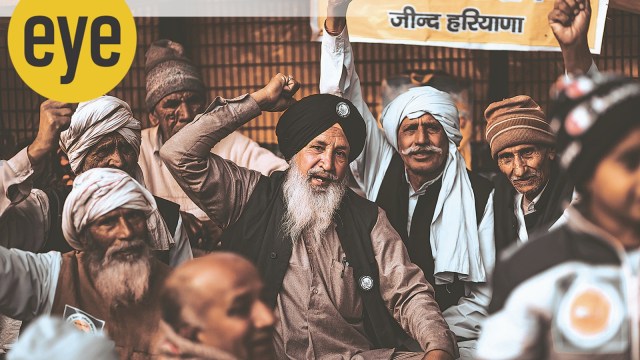

Farmers Protest 2020, credit: Wikipedia Commons

Farmers Protest 2020, credit: Wikipedia CommonsWhen Gurbaz played a recording of his latest speech on his phone, his friends, lying around him under the canvas tent on beds of straw and dusty mattresses, congratulated him on a budding political career, before offering some unwelcome advice: “You know, you need to slow down. You talk like a bullet train,” said one of the men, to roars of laughter from everybody and a blush appearing on Gurbaz’s cheeks.

When he got to know that men and women from his village in Punjab were leaving for the Capital to protest the new farm laws, he thought he wouldn’t have anything to do with them. “I had plans to get married and go to Canada,” he said, in one of the tents that became a subject of Nishtha Jain’s Farming the Revolution, a documentary on the 2020 farmers’ movement demanding protection from corporate hoarding of edible grains, that recently screened at the Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF). “I thought there’s nothing in this country for someone like me,” he said, suggesting the rising number of farmer suicides, crushing debt and falling price parity that characterises agriculture in India now. “But then I remembered Bhagat Singh.”

The 21-year-old communist revolutionary, who tossed a bomb into then-British parliamentary proceedings in 1929 India and was hanged for the transgression, was the namesake of a library running at one of the protest sites on Delhi’s border.

Jain, of Gulabi Gang (2012) and The Golden Thread (2022) fame, arrived at Delhi’s Bahadurgarh border at a time when the farmers were already suspicious of mainstream media. ‘Khalistani terrorists’, ‘Urban Naxals’, ‘Leftists’, ‘Maoists’ were only some of the labels being used in news bulletins, political rallies and living rooms for the men and women who had left their homes, put up camp on Delhi’s border and refused to return till their demand for a Minimum Support Price on all crops was met. “What I experienced, I just had to stay and record for posterity,” said Jain, in a post-screening discussion. “(The farmers) were suspicious in the initial days. They would ask us questions so we could prove our credentials. But when they saw us every day, we slowly built trust.”

Jain’s team was small — three crew members and a driver — and the only money she had was her own. Funding requests were being rejected but she couldn’t stop shooting, the protest was carrying on, and she was accumulating hundreds of hours of footage with multiple characters. Then, on November 19, 2021, when she was packing her bags for a pitching forum in Amsterdam, she heard that Prime Minister Narendra Modi had repealed the laws — a full year after the protests (and her shooting) had begun. “Everybody was like, my gosh, you’re so lucky, now (funders) will be interested. (The story) has a beginning, middle and end,” she said. “(It was) the farmers’ love that kept me going… If I had to feed my team, I would have packed up and gone home, but they fed us at the langar. We’d reach a village and people would host us in their homes.”

Director Nishtha Jain

Director Nishtha Jain

This community lights up the documentary. Shots of men cooking towers of rotis and packing them in aluminium foil; women massaging each other and discussing the irony of protesting the same “Ambanis-Adanis” whose malls they work in back home; concerts and volleyball matches and newspapers to combat misinformation, litter the documentary.

But that immersion comes at a cost — violent incidents that characterised the protests, like the alleged gangrape of a woman at the Tikri border and the alleged lynching and murder of a Dalit man at the Singhu border, didn’t make it to the runtime.

“I wasn’t there so I didn’t have the footage. I didn’t know how to build it up,” said Jain, though the film often uses second-hand footage and voiceovers, and a video of the Dalit man’s lynching was circulated soon after. “I’d like to include many things but once I bring them in, I have to unpack them — I have to bring in who did it, how it happened… But the incident was important.”

One of the strongest characters in Jain’s script is Gurbaz, who, she said, “started from zero”, knowing nothing about farm unions and the new laws, but went on to bolster the camaraderie of the protests with speeches and distribution of resources, saying to his despairing mother that he was travelling to the protests for a noble reason, à la his hero, Bhagat Singh.

“I could have censored myself; I didn’t,” said Jain, on including footage with slogans critical of Prime Minister Modi. “People were very angry with us. My editor said I should prepare for asylum. But all of us are self-censoring all the time, and that is creating an atmosphere of fear. The more we speak out, we create a different atmosphere. That’s why I included (what I did).”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05