For a long time, history textbooks said that thousands of years ago, men hunted animals while women gathered fruits and firewood, and nurtured their kids. This commonly accepted view was also known as ‘Man, the Hunter’.

But over the decades, several studies have challenged this idea, which is also used as an example to justify the division of labour on the basis of sex – that men and women should be restricted to certain professions and roles, because of their biological characteristics.

Two recent studies have now said that not only did women participate in hunting big animals just as the men did, but their biology gave them certain advantages as well.

First, what exactly did ‘Man, the Hunter’ say?

The theory gained ground in the 1960s, based on research from anthropologists Richard Borshay Lee and Irven DeVore. It argued that the hunting of animals drove a lot of evolutionary developments in humans and their societies.

A National Geographic article from 2007 explains: “Much of our anatomy, according to the Man-the-Hunter theory, was the result of adaptations for hunting. You have to stand tall above the savannah grass, for example, to spot your game. You need to make weapons. And a bloody-minded psychology helped too.”

However, the theory was challenged with subsequent research. One view was that it ignored the role of women as it did not count them as participants in hunting. A study in May this year from American researchers analysed 63 present-day foraging societies across the world. It found that 50 (79 per cent) of them had documentation on women hunting, suggesting biology and processes such as pregnancy and menstruation had little role to play in participation in hunting.

What does the new research say about women’s role in hunting?

Biological anthropologist Sarah Lacy (from the University of Delaware) and biologist Cara Ocobock (from the University of Notre Dame) published two papers in the journal American Anthropologist in September this year, on the role of women hunters.

Story continues below this ad

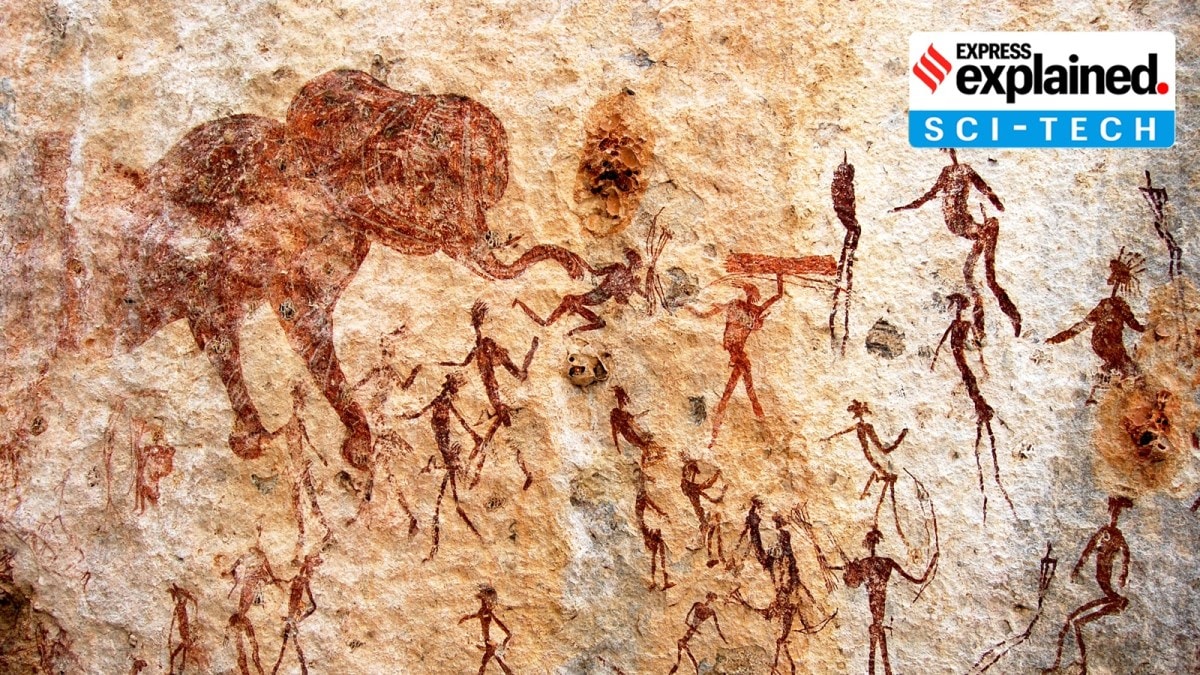

They spoke of the Paleolithic era (between 2.5 million to 10,000 years ago) when humans used primitive tools and began residing in basic structures such as huts. It was right before the advent of agriculture, which led to humans building settled communities.

The researchers made a case for ‘Woman, the Hunter’, from a physiological and archaeological lens:

Physiology: They argue that on average, the role of the estrogen hormone is not taken into account to speak about female physical capabilities. Their study shows that “females may be metabolically better suited for endurance activities such as running, which could have profound implications for understanding subsistence capabilities and patterns in the past.”

They preface this by acknowledging that biologically, there are differences between females and males. In an article in Scientific American on November 1, they wrote, “Females are metabolically better suited for endurance activities, whereas males excel at short, powerful burst-type activities. You can think of it as marathoners (females) versus powerlifters (males). Much of this difference seems to be driven by the powers of the hormone estrogen.”

Story continues below this ad

Estrogen is produced more in females than males. Whereas, males produce more testosterone – linked to muscle growth. “In addition to helping regulate the reproductive system, estrogen influences fine-motor control and memory, enhances the growth and development of neurons, and helps to prevent hardening of the arteries,” they wrote.

It also improves fat metabolism. So, during exercise, “estrogen seems to encourage the body to use stored fat for energy before stored carbohydrates. Fat contains more calories per gram than carbohydrates do, so it burns more slowly, which can delay fatigue during endurance activity.” As an example, the researchers cited studies that show women experiencing lesser muscle breakdown after exercise when compared with men.

Archaeology: Burial remains for males and females, and techniques for doing so, also shed light on the society of that time. According to the researchers, the remains of our closest extinct human relatives, the Neandertals, do not differ in their trauma or injury patterns based on sex.

“This finding suggests that they were doing the same things, from ambush-hunting large game animals to processing hides for leather,” the researchers wrote.

Story continues below this ad

Between 45,000 and 10,000 years ago, males do show higher rates of a set of injuries to the right elbow region, reflecting the frequency of the action of throwing spears. “But it does not mean women were not hunting, because this period is also when people invented the bow and arrow, hunting nets and fishing hooks,” they said.

Further, the fact that females and males were buried in the same way between 35,000 to 10,000 years ago, and interred with the same kinds of artifacts, also suggests a lack of differentiation.

What changed?

They wrote, “It was the arrival some 10,000 years ago of agriculture, with its intensive investment in land, population growth and resultant clumped resources, that led to rigid gendered roles and economic inequality.”

This is a prevalent view, and one of the reasons for it is the presence of different tools found in the graves of men and women from that period. For example, hunting tools were found in male sites, but tools more suited to working with animal hides and skins were found in female sites, suggesting a division in the work they did.

Story continues below this ad

But at least since the 1960s, research has found that hunting tools from thousands of years ago have been discovered in female burial setups. A 2020 study from the University of California, Davis, found that between 30 per cent and 50 per cent of the hunters were female, while analysing burial records from the Americas. The new studies add to growing evidence, aimed at correcting the modern-day biases that might have been imposed on other periods of history.