Why the delimitation exercise is seen as a political battle between the BJP and the rest

Opposition parties have repeatedly slammed the government for linking the implementation of women’s reservation with delimitation, claiming there was no reason or requirement to connect the two.

Indeed, the last time the women’s reservation Bill was discussed in Parliament, there was no such linkage.

Indeed, the last time the women’s reservation Bill was discussed in Parliament, there was no such linkage.

The Women’s Reservation Bill, providing 33 per cent quota to women in Lok Sabha and state Assemblies, was swiftly passed by both Houses of Parliament last week, but its fate hangs in balance because of its dependence on the delimitation exercise.

Opposition parties have repeatedly slammed the government for linking the implementation of women’s reservation with delimitation, claiming there was no reason or requirement to connect the two. Indeed, the last time the Women’s Reservation Bill was discussed in Parliament, there was no such linkage.

By making the women’s reservation contingent on delimitation, the government seems to be aiming for several objectives. The delimitation exercise will increase the number of both Lok Sabha and Assembly constituencies. In that scenario, reservation of one-third of seats for women is likely to leave the current number of male legislators largely undisturbed. This could mean greater acceptability of women’s reservation within the political class.

But a much bigger objective seems to be an attempt to force the hands of the Opposition parties, mainly those from south India, on the delimitation exercise.

Delimitation is a Constitutional mandate, to be carried out after every Census, to readjust the number of seats and their boundaries on the basis of latest population data. But the number of seats for the Lok Sabha and state Assemblies has remained frozen for the last 50 years, because of opposition from political parties from the South.

And there is no inclination among them to allow delimitation even now, mainly because any such exercise would result in Lok Sabha seats in north Indian states increasing much more sharply, as the population rise here has been greater. And if this happens, the BJP stands to gain the most.

Reservation in a larger pie

One of the reasons women’s reservation did not become a reality in the last 35 years was the fear among male politicians of having to let go of their seats. A 33 per cent reservation in the current 545-member Lok Sabha would mean 182 seats being kept for women. Only 363 seats would be available for men. The current Lok Sabha has 467 men. But delimitation could preserve the political fortunes of the current group of male politicians.

If, as a result of the delimitation exercise, the strength of the Lok Sabha increases to 770, as some calculations suggest, 257 seats would be reserved for women, and the remaining 513 could be available for men to contest. This would mean that political parties would have to deal with much lesser complications in accommodating the political interests of their male leaders.

Checkmate Opposition

But the bigger design of the government is not lost on the Opposition parties. As one Opposition leader told The Indian Express, the attempt clearly is to make the delimitation exercise a foregone conclusion.

“Delimitation is a contentious issue. But now, a resistance to the delimitation exercise ahead of 2029 polls would give a handle to the BJP to accuse the Opposition of creating hurdles for the women’s reservation Bill,” he said.

DMK leader Kanimozhi echoed this concern in last week’s Parliament session and said delimitation was now “a sword hanging on our head”. But she indicated that the Opposition was not ready to surrender.

“If delimitation is going to happen on population census, it will deprive and reduce the representation of the south Indian states. Why should the implementation (of women’s Bill) be connected to delimitation?” she said while reading a statement from Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M K Stalin. “There is fear in the minds of the people of Tamil Nadu that our voices will be undermined,” she said.

Former law minister and now independent MP Kapil Sibal said the linkage with delimitation could delay the implementation of women’s reservation even beyond 2029. “I want the Prime Minister and the Home Minister to come to the House and say that if they do not complete the process of delimitation by 2029, they will resign,” Sibal said.

Gains for north Indian states

The main rationale of delimitation is to ensure that every state has equitable representation in the Lok Sabha on the basis of its population, with the same logic running down within the states for Assemblies. The idea is to ensure that every MP, as far as possible, represents the same number of people. In the 1977 Lok Sabha, for example, every MP in India represented about 10.11 lakh people, on an average (see box). While there are large variations, especially in small states, the attempt is to keep this number in as tight a range as possible.

But there is no restriction on what this number should be. In fact, if we attempt to retain the same number as in 1977, the strength of the Lok Sabha would have to be expanded to nearly 1,400, due to the increase in population. But the new Lok Sabha has been built with the maximum capacity of 888 seats. That means the average population size of every constituency would have to go up.

But whatever the calculation, the number of Lok Sabha seats in states like Uttar Pradesh or Bihar are likely to jump much more than south Indian states. The jump would be much more pronounced mainly because the number of seats has been forcefully kept unchanged for 50 years now. If the delimitation exercise had happened after every Census, as mandated in the Constitution, seats for the north Indian states would have gone up progressively and not all of a sudden. North Indian states can argue that they are terribly underrepresented right now.

BJP stands to gain most

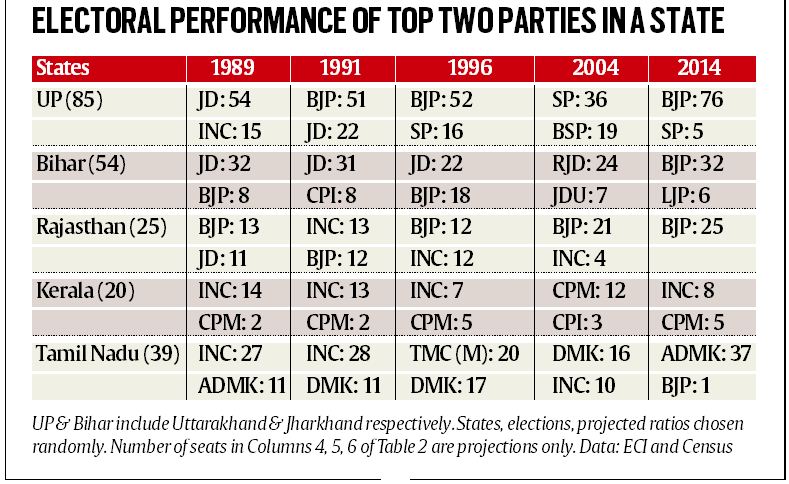

The BJP’s keenness on delimitation is understandable, and so are the apprehensions of the Congress and other Opposition parties. Following the rise of the BJP through the late 1980s and early 1990s on the back of the Ram Temple movement, and the arrival of social justice parties following the Mandal movement, Congress has been doing poorly in the Hindi heartland. From the high of 51 seats in UP (including Uttarakhand) and 30 seats in Bihar (including Jharkhand) in 1980, its tally has fallen to just 1 in the erstwhile united UP and 2 in Bihar and Jharkhand (see box).

Of the 52 seats won by the Congress in 2019, 15 came from Kerala and eight from Tamil Nadu. Even in 2004, when it had won 145 seats and regained power, a majority of its victories had come from south Indian states, with 29 from Andhra Pradesh. In 2009, when it won again, Andhra Pradesh returned 33 seats.

In contrast, BJP’s consolidation in north India is near total now. Delimitation is only going to strengthen its hold over national politics.

Delimitation continues to be a political hot potato. By linking it with women’s reservation, BJP has tried to press its advantage, but the Opposition has not yet opened its cards. In this political tussle, the women’s reservation Bill could become the casualty yet again.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05