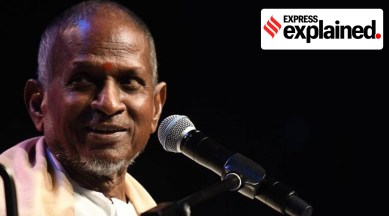

Ilayaraja and his court battles explained: who owns the rights to a film song?

Ilayaraja has challenged a single-bench order that permanently prevented him from asserting his copyright over some of his own musical work. What is the case about? Who owns a song, according to law?

Last week, the Madras High Court admitted a plea from composer and lyricist Ilayaraja, challenging a single-bench order that had permanently prevented him from asserting his copyright over his own musical work and master recordings for 30 films of the 1980s.

What is the case about?

Ilayaraja contended that he had copyright over his musical work as composer and author, which the copyright of the owner of the film could not impeach. His lawyers said digital rights came into existence after 1996, and the music company cannot be allowed to hold rights to his work.

The court in 2020 held INRECO to be the owner of the copyright with exclusive right to exploit and utilise Ilayaraja’s musical works, except that he had moral and literary rights to his works. The court ruled that when a song is part of a film, which is a composite work, the producer will be the owner have rights to the authorship. At the same time, the court prohibited the music companies from making profits off the composer’s songs at reality shows and radio channels without his permission.

Who owns a song, according to law?

A song usually comprises three elements – lyrics, tune and voice. According to the Copyright Act, 1957 (amended in 2012), there is a clear line between the owners and the authors of copyright under the Copyright Act. The Act gives the right of royalty to lyricists and composers if the song plays outside of the cinema halls. According to section 2(d)(ii),a composer of musical work is an author and lyricist is an author in relation to literary work (lyrics) under section 2(d)(i) and the producer in relation to sound recording is an author under section 2 (d)(v). If the song is a part of a film and is going to be played as is, then the producer will be the owner of the song. The rule is the same if it’s an album owned by a recording label.

Also, because a song has three different elements, all three can be registered separately under literary work, musical work and a performer’s rights. The song as a whole (the master sound recording) will still be with the producer (music label or film producer).

If a restaurant, for example, is going to play songs by A R Rahman, or if Spotify will play a Shankar Ehsaan Loy playlist, these will be outside the scope of the films in which they exist. The composers, lyricists and the singers will receive a percentage of the royalties because the restaurant is charging the customers who are listening to the music while Spotify is also earning through its subscribers.

It’s essential for film and music production companies to sign on third parties for issuing public performance licences and the collection of the fees. Some such organisations are Indian performing Rights Society Limited and Phonographic Performance Limited among others..

Yes, from a time when all music rights were owned by music labels which, he alleged, did not pay him royalties. In 1981, with his friend M R Subramanian, he started his own company, Echo, which had ownership of all his songs under a five-year deal. But in 1992, Ilayaraja left Echo, and filed a suit against it in 2014, claiming he had not received any royalty through the sale of cassettes. The judge ruled in favour of the company and allowed Ilayaraja control only over non-theatrical use of his music.

In 2013, Ilayaraja had filed a case against AGI Music, a music company based in Malaysia, which he said was exploiting his music beyond the five years for which it had acquired the rights. The court ruled in his favour, saying the agreement was indeed for five years and not 10 as AGI claimed.

In 2017, Illyaraja sent a legal notice to his long-time collaborator S P Balasubramanyam, asking him not to perform his music without his consent and licence. This raised a debate with many arguing that along with the lyricist, Balasubramanyam too owned part of the songs he had sung.

In 2018, a group of producers led by P T Selvakumar filed a case against Ilayaraja demanding that he pay part of the royalty he collects to the producers of the films these songs were originally in. They argued that producers commission these songs and engage and pay a number pf technicians to create them. A few months later, Ilayaraja said in a video statement, “I hold the rights of all my songs… If you wish to sing and perform my songs on stage without prior intimation, you are liable for legal action.”

What next in the ongoing case?

In his appeal, Ilayaraja has contended that the single-judge bench had erred in understanding the concept of authorship and ownership. He claimed that the order was passed without material evidence and without questioning the necessary parties (producers of films).

A division bench comprising Justices M Duraiswamy and T V Tamil Selvi has now ordered a notice to the defendants — INRECO in Chennai, Agi Music Sdn Bhd in Malaysia and Unisys Info Solutions Private Limited in Haryana — seeking their response.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox