July 30, 2023, is the 201st birth anniversary of Wajid Ali Shah, the last Nawab to sit on the throne of Awadh. Wajid Ali Shah was a man of many contradictions — a king who never had much power but who managed to maintain a ‘court’ to his dying day; a ruler whose deposition contributed to the Revolt of 1857 but who never showed any inclination of fighting the British; an aesthete who wrote much about love and passion, but treated his (numerous) wives and children rather callously.

Yet it is the last 30 years of his life, spent in Calcutta, that best highlight the unique character of Wajid Ali Shah, whose answer to the reverses of destiny was to pretend they hadn’t happened, and who, though never respected by the British, held enough weight to be treated with a generous pension and personal politeness all his life.

Exile: ‘naiyhar chhooto hi jaaye‘

After he was deposed as the ‘king’ of Lucknow — a title given by the British — Wajid Ali Shah and his family planned to sail to England and plead their case directly with Queen Victoria, a fellow sovereign they assumed would be more sympathetic to their cause. Wajid Ali Shah, his mother Malika Kishwar Bahadur Fakhr-uz-Zamani, or Janab-i-Aliyyah, and his brother Sikandar Hasmat, along with ministers and relatives, landed in Calcutta for this purpose.

The nawab felt the loss of Lucknow bitterly, and is said to have composed ‘Babul mora naiyhar chhooto hi jaaye (father, my home is now lost to me)’ to express his separation from his motherland. His subjects, meanwhile, lamented, “Angrez bahadur ain, mulk lain linho (the brave English came and took away the nation)”, as historian Rudrangshu Mukherjee writes.

Photo and caption from the Royal Collection Trust: ‘In this subversive painting, the King has abandoned the throne to join his musicians and play the tabla drums, among the lowest status musical instruments’.

Photo and caption from the Royal Collection Trust: ‘In this subversive painting, the King has abandoned the throne to join his musicians and play the tabla drums, among the lowest status musical instruments’.

Once the royal party arrived in Calcutta, plans somehow changed, and the dowager queen and her other son left for England, while Wajid Ali Shah stayed behind. The nawab was said to be ill, though many believed he was weaseling out of a difficult journey, letting his 50-something mother travel instead.

The British never did have a high opinion of Wajid Ali Shah, branding him as ineffectual, uninterested in governance, and given to the pleasures of poetry and passion from his crown prince days. However, they had underestimated the fact that despite his faults, the nawab, patron of arts and builder of palaces, was popular in Awadh, and his deposition had rankled.

Story continues below this ad

This was made clear when Awadh joined the Revolt of 1857, and Wajid Ali Shah, in faraway Calcutta, was promptly imprisoned in Fort William. Here he remained for two years, despite the Revolt being quelled and despite him writing numerous letters to the British, even offering to lead Lucknow’s forces under his own banner in support of the East India Company.

After he was finally freed from Fort William and allowed to move to Garden Reach on the outskirts of then-Calcutta, Wajid Ali Shah quickly set about establishing a faux version of the kingdom he had been forced to give up, ironically getting the British to finance some of it.

A ghost ‘court’ is created

The residence Wajid Ali Shah was assigned was in the Garden Reach area (or Metiaburz), a two-mile stretch by the Hooghly, where high-ranking Company officials had built country homes. Along with a monthly pension of Rs 1 lakh, the Nawab was allotted the unimaginatively named Bungalow no. 11, once the home of Sir Lawrence Peel, the Chief Justice of Calcutta, and then belonging to Chand Mehtab Bahadur, Raja of Burdwan. The bungalow got a name fitting its colourful new occupant, ‘Sultan Khana’, and a private mosque was built inside.

Wajid Ali Shah had been followed from Lucknow by a large number of his over-365 wives, children, ministers, bodyguards, tradesmen, cooks, tailors, attenders, entertainers, performers, and so on, who were already living in Garden Reach while the nawab was imprisoned.

Soon, two adjoining bungalows also had to be rented. Once released in July 1859, the deposed ruler started issuing farmans (royal orders) about who could live where. Those with no allotted place simply squatted, building houses and huts in the large gardens of the three properties. Eventually, the nawab got the British to buy all three properties for him, and embarked on a remodelling and redecorating project on a royal scale indeed.

Story continues below this ad

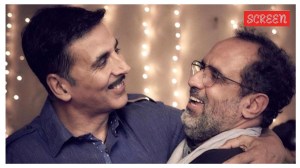

Wajid Ali Shah and his wives watch a performance. (Photo: Royal Collection Trust)

Wajid Ali Shah and his wives watch a performance. (Photo: Royal Collection Trust)

Author Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, in her book The Last King in India: Wajid Ali Shah, so describes Garden Reach: “Fifty-one marble fountains erected on masonry bases played in front of the houses and each fountain was named in fanciful fashion as ‘Fairy Spring’, ‘Example of the Sun’, ‘Specially noted’ and so on… Within the ‘Verdant Garden’ were numerous ‘flower tube pillars’, dovecotes, fountains, two small pavilions named the ‘Diamond’ and the ‘Special’, as well as two tiger enclosures… There was a vine-trellis (in imitation of the Great Vine at Qaisarbagh [in Lucknow])…”

There were dovecoats and parrot houses, a large menagerie from which a tigress would eventually escape and injure a German man, and the gardens were lit by the modern and expensive gas lamps. There were kite-flying and animal-fights. The elaborate dance, music, and poetry events of Lucknow were brought back to life, and the nawab is credited with popularising in Bengal Kathak and the biryani-with-potato.

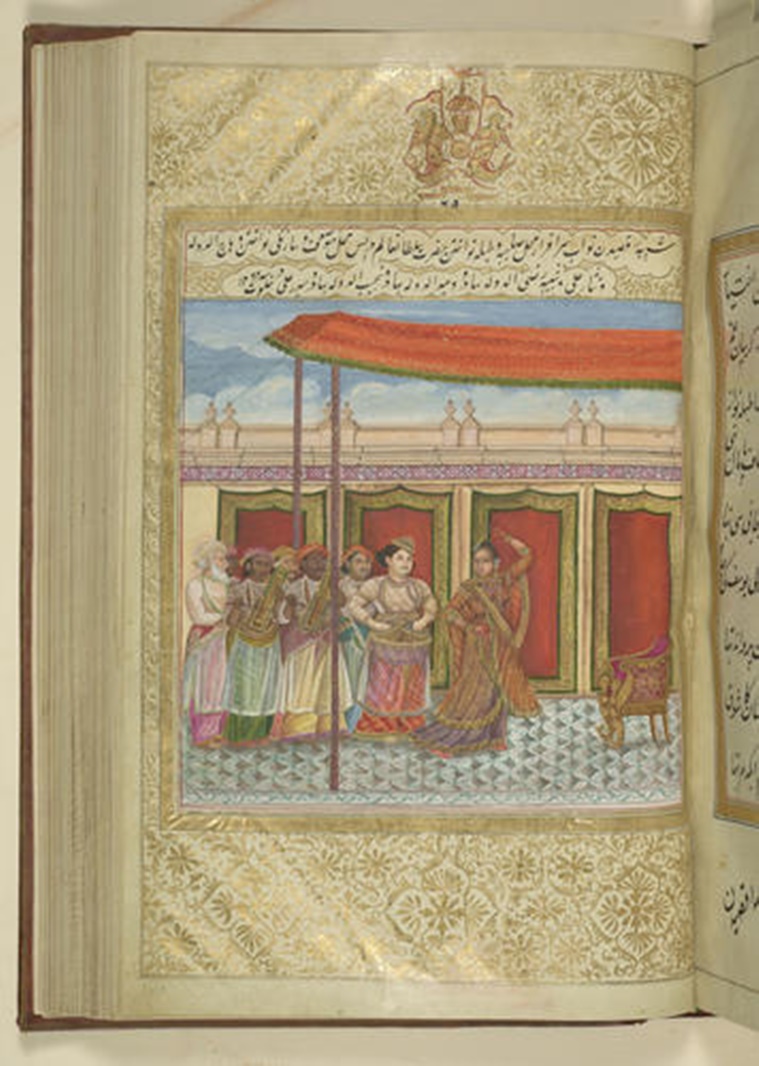

Imambara Sibtainabad, built by Wajid Ali Shah. ((Photo: Sudipta Mitra)

Imambara Sibtainabad, built by Wajid Ali Shah. ((Photo: Sudipta Mitra)

Meanwhile, the nawab bought gem-studded utensils, shawls, jewellery, often through agents, who told him inflated prices and pocketed the difference. Wajid Ali Shah’s pension, though generous, was nowhere equal to all this, and he soon went heavily under debt. Things reached a point where his moneylenders sued him, and the British had to step in, by enacting a law that shielded the nawab from court cases.

They also got an accountant to go over the nawab’s finances, and, by throwing out some claims and discovering the fraudulent nature of others, whittled down his debt to a much more manageable sum, which he agreed to pay off in installments. Throughout his stay in Calcutta, the nawab got the British to allow his extravagance by enacting several laws that sealed him off from persecution — a neat reversal from the British never paying back the money Awadh had lent them.

The British have a problem on their hands

Story continues below this ad

Why did the British keep bailing Wajid Ali Shah out, and did not act against his activities they disapproved of? It was due to a combination of factors, including the realisation that the nawab still carried emotive appeal and personal popularity. Till his death, the British feared that public humiliation or physical assault of the nawab could incite a rebellion.

The second was the hope that Wajid Ali Shah would die soon, thanks to his his hedonistic lifestyle and his own hypochondria.

But third, and very important, was the personality of Wajid Ali Shah, who refused to acknowledge that his reduced circumstances required a change in his behaviour. His spending was not his only pretension to royalty. He carried on with his ‘court’, paying salaries to thousands of people.

He allowed a rich cultural life to flourish around him. He wrote regularly to Queen Victoria and other senior officials as the king he had once been. Llewellyn-Jones writes of his letters, “…underneath all the elaborate Persian similies and archaic forms of address remains the impression of a man writing to his peers, and expecting his letters to be read, if not necessarily answered.”

Story continues below this ad

Wajid Ali Shah never for a moment forgot who he had been, and ensured that to be stronger part of his identity than what he had become. This, in a nation struggling with feelings of inferiority under an overbearing imperial power, was its own kind of heroism. Little wonder, then, that even today, the name ‘Wajid Ali Shah’ holds charm and the thrill of bygone ‘achche din’.

Photo and caption from the Royal Collection Trust: ‘In this subversive painting, the King has abandoned the throne to join his musicians and play the tabla drums, among the lowest status musical instruments’.

Photo and caption from the Royal Collection Trust: ‘In this subversive painting, the King has abandoned the throne to join his musicians and play the tabla drums, among the lowest status musical instruments’. Wajid Ali Shah and his wives watch a performance. (Photo: Royal Collection Trust)

Wajid Ali Shah and his wives watch a performance. (Photo: Royal Collection Trust) Imambara Sibtainabad, built by Wajid Ali Shah. ((Photo: Sudipta Mitra)

Imambara Sibtainabad, built by Wajid Ali Shah. ((Photo: Sudipta Mitra)