Birsa Munda’s 124th death anniversary: Significance of the tribal leader’s contributions

Birsa Munda achieved a God-like status among his followers and led one of the earliest tribal struggles against British rule. Here is a brief look at his life.

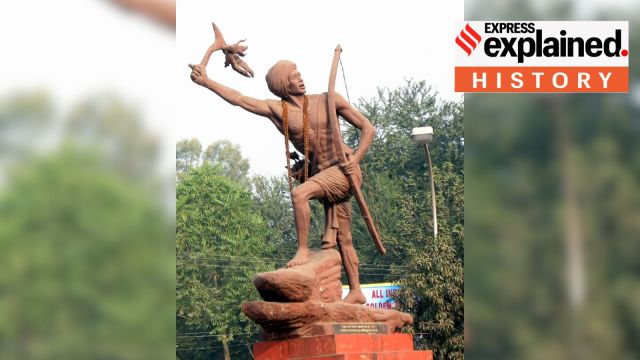

Birsa Munda was born on November 15, 1875, at a time when his community was witnessing major changes amid the advent of British colonial rule. (Via Wikimedia Commons)

Birsa Munda was born on November 15, 1875, at a time when his community was witnessing major changes amid the advent of British colonial rule. (Via Wikimedia Commons)Marking the 124th death anniversary of revolutionary tribal leader Birsa Munda, Jharkhand Chief Minister Champai Soren paid his tributes on Sunday (June 9).

“Salutations to Lord Birsa Munda ji! Our government, following the path shown by you, is striving to bring about a positive change in the living standards of the tribals, natives and common people of Jharkhand,” he wrote in a post on X.

Why is Birsa Munda still seen as a revered figure among tribal communities today, and what was the significance of the struggle he waged?

Laying the ground for revolt

Birsa Munda was born on November 15, 1875, at a time when his community was witnessing major changes. The Mundas, a tribe of nomadic-hunters-turned-farmers who lived in the Chotanagpur region in today’s Jharkhand, had to bear the brunt of a series of adverse policies and events.

Before colonial rule, the prevalent system of land ownership here was known as “khuntkatti”. It was based on the principle of customary rights, without the involvement of landlords.

However, the enactment of the Permanent Settlement Act (1793) led to a transformation and helped colonialism make its inroads in rural India. To maximise its revenue, the East India Company relied on the law to ratify the zamindari system for land revenue collection. This created dual classes — of land-owning zamindars who were viewed as outsiders or “dikus” by the indigenous residents, and the “ryots” or tenants.

The Act allowed the dikus to claim ownership rights using a deed which specified a precise area. This displaced the indigenous dwellers and denied them access to the land they had cultivated for generations.

Compounding the problem for the community was a range of other debilitating policies, including the exploitation of tribal people through the “begar” system of forced labour, the forced dependence on money-lenders for credit and the replacement of traditional clan councils with courts.

To cap it all, the onset of famines in 1896-97 and 1899-1900 resulted in mass starvation.

‘Dharti ka Abba’, bhagwaan Birsa

Birsa Munda spent much of his childhood moving from one village to another with his parents.

He completed his primary education at Salga under the guidance of his teacher Jaipal Nag. Birsa converted to Christianity on Nag’s recommendation to join the German Mission school, but opted out of the school in a few years.

The impact of British rule, as well as the heightened activities of the Christian missionaries in the area, made many tribals cynical about the presence of the dikus.

Munda spent most of his time between 1886 and 1890 in Chaibasa, close to the centre of the Sardari agitation. Aimed against British rule, it was peaceful in its nature led by the Oraon and Munda tribes.

This inspired him to join the anti-missionary and anti-colonial cause. By the time he left Chaibasa in 1890, Birsa was strongly entrenched in the movement against the British oppression of the tribal communities.

Munda soon emerged as a tribal leader who brought people together to fight for these issues. Leading the faith of ‘Birsait’, he became a God-like figure who came to be referred to as ‘Bhagwan’ (God) and ‘Dharti ka Abba’ (father of the earth) by his followers.

As followers flocked to the new religion, Birsa advocated against superstition and urged his people to renounce begging and animal sacrifice, asking them to worship only one God. In the process, members of the Munda and Oraon communities joined the Birsait sect, posing a challenge to British conversion activities.

The Ulgulan movement and aftermath

Birsa Munda launched the Ulgulan movement in 1899, using weapons and guerrilla warfare to drive out foreigners. He encouraged the tribals to follow the Birsa Raj and to not comply with colonial laws and rent payments.

However, the British were soon able to halt the movement through the superior strength of their forces. On March 3, 1900, Munda was arrested by the British police while he was sleeping along with his tribal guerilla army at the Jamkopai forest in Chakradharpur.

It is believed he died in Ranchi Jail due to an illness on June 9, 1900, at the young age of 25. Though he lived a short life and the movement died out soon after him, Birsa Munda’s mobilisation of the tribal community for protecting their land rights was remarkable, being one of the earliest such attempts.

The movement also contributed to the government’s repeal of the begar system, and led to the Tenancy Act (1903) which recognised the khuntkhatti system. The Chotanagpur Tenancy Act (1908) later banned the passage of tribal land to non-tribal folks.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05