Three days after Nagpur saw violent clashes, curfew was relaxed in areas of the city on Thursday (March 20). At the heart of the violence is the tomb of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, which the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) and other Hindutva bodies want removed.

Aurangzeb died more than 300 years ago, on February 20, 1707. While the tombs of his predecessors are ornate structures where tourists from across the world flock to, his own humble grave lay largely forgotten till those seeking to avenge historical wrongs turned their eyes to it. Yet, Aurangzeb’s grave and the circumstances of his death hold many lessons for those interested in learning from history.

Aurangzeb ruled for almost 50 years, the longest serving ruler of one of the most powerful ruling dynasties of the world — the English word ‘mogul’ is still used for a powerful person. But the emperor of Delhi is buried in far-away Khuldabad, and even some Mughal officials have tombs bigger and grander than his.

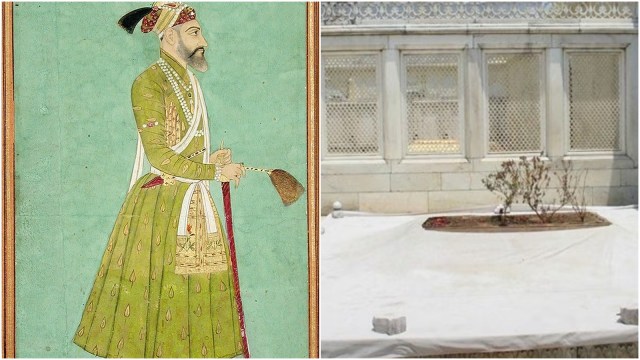

The grave of Aurangzeb. (Express photo by P Vaidyanathan Iyer)

The grave of Aurangzeb. (Express photo by P Vaidyanathan Iyer)

Why is Aurangzeb buried in Maharashtra?

Aurangzeb spent the last years of his life with his vast empire collapsing around him. He was facing an agrarian crisis, the nobility was slowly deserting him, and militarily, he was besieged by the increasingly dominant Marathas. It was on a campaign against the Marathas in the Deccan that death came to Aurangzeb, by then nearing 90 years of age.

“It was Aurangzeb’s own wish to be buried in a simple tomb, in keeping with Islamic austerity. His grave lies inside the complex of the dargah (shrine) of Sheikh Zainuddin, a 14th-century Chishti saint,” historian Ali Nadeem Rezavi of Aligarh Muslim University told The Indian Express.

Also buried in the complex are Azam Shah, one of Aurangzeb’s sons who briefly succeeded him as emperor, the first Nizam of Hyderabad, Asaf Jah I (1724-48), and Asaf Jah’s son, the second Nizam, Nasir Jung (1748-50).

American historian Catherine Asher, in her Architecture of Mughal India, writes of Aurangzeb’s grave, “…The emperor’s open-air grave, in accordance with his final wishes, was marked by a simple stone cenotaph, although in the early twentieth century it was faced with white marble. The top was filled with earth so plants might grow.”

Story continues below this ad

Rezavi said the erecting of the white marble screen was ordered by British Viceroy Lord George Curzon, to honour one of the longest-serving kings of India.

A more detailed description of Aurangzeb’s burial is given in Saqi Musta’d Khan’s Maasir-i-Alamgiri, translated into English by historian Sir Jadunath Sarkar. It says, “… According to His Majesty’s last will, he was buried in the courtyard of the tomb of Shaikh Zainuddin [at Rauza, near Daulatabad] in a sepulchre built by the emperor in his own lifetime…The red stone platform (chabutra) over his grave, not exceeding three yards in length, two and half yards in breadth, and a few fingers in height, has a cavity in the middle. It has been filled with earth, in which fragrant herbs have been planted.”

Rauza was later renamed Khuldabad, as Aurangzeb was given the title of Khuld-Makani, or one who resides in eternity.

Historian Rana Safvi told The Indian Express, “Rauza means tomb. Khuldabad was earlier known as Ruaza as it housed the shrines of many Sufi saints.”

The many stories the grave tells

Story continues below this ad

Aurangzeb is known as a religious bigot, whom historian William Dalrymple called “a depressingly puritanical figure”. Yet, he was also a man of contrasts, which are reflected in his grave too.

Aurangzeb was a hardline Sunni Muslim, yet he is buried in the dargah of a Sufi saint. Asher writes, “Toward the end of his life, Aurangzeb noted that visiting graves was not acceptable in orthodox Islam. Nevertheless, the location of his own tomb indicates that he personally never lost esteem for saints.”

Also, his grave is most similar to that of his older sister Jahan Ara, who lies buried in a simple grave in the complex of the Nizamuddin Auliya dargah in New Delhi. Yet, Jahan Ara and Aurangzeb were at odds most of their life — she was on the side of Prince Dara Shikoh in the murderous battle of succession among Shah Jahan’s sons, and remained a loyal companion to her father when he was imprisoned by Aurangzeb.

The grave of Jahan Ara, in the Nizamuddin Auliya dargah complex in New Delhi. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The grave of Jahan Ara, in the Nizamuddin Auliya dargah complex in New Delhi. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The graves of the first six Mughal kings (known as ‘great Mughals’) also reflect the fortunes of the empire. Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan all have beautiful, spectacular tombs that are a statement of the grandeur of their empire. Also, none of the ‘great Mughals’ ascended the throne without some turmoil in succession.

Story continues below this ad

In this context, Historian Michael Brand, in a 1993 research paper (Orthodoxy, Innovation, and Revival: Considerations of the Past Imperial Mughal Tomb Architecture) makes an interesting point: “ In fact, while Babur and Aurangzeb willed their own simple burials…Humayan, Akbar, and Jahangir were all entombed in structures built by their sons and successors… it can be asked whether Mughal tombs were really erected to commemorate dead emperors or as victory monuments for the survivors of internecine warfare.”

Aurangzeb’s grave, thus, makes two points: while he was able to maintain his control over his burial too, it is also true that his successors were no match to those of his father and grandfathers’, and the empire was left with little grandeur to proclaim through a monument. The Mughal empire, from Babur to Aurangzeb, had in a sense come full circle.

Aurangzeb himself was deeply conscious of his failures towards his death. Jadunath Sarkar, in his book ‘A Short History of Aurangzib‘, quotes a letter the king wrote to his son Prinze Azam in his last days, “I know not who I am and what I have been doing…I have not at all done any (true) government of the realm or cherishing of the peasantry…Life, so valuable, has gone away for nothing.”

The grave of Aurangzeb. (Express photo by P Vaidyanathan Iyer)

The grave of Aurangzeb. (Express photo by P Vaidyanathan Iyer) The grave of Jahan Ara, in the Nizamuddin Auliya dargah complex in New Delhi. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The grave of Jahan Ara, in the Nizamuddin Auliya dargah complex in New Delhi. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)