Iran-Israel ceasefire: After the fighting has stopped

Trump has forced a fragile truce on Israel and Iran. Tehran needs space to negotiate and recuperate. Israel has shown it can conduct a stand-off war against the Iranian homeland. What next for Iran and the region?

Workers sit next to a building at the Weizmann Institute of Science destroyed by an Iranian missile in Rehovot. (Source: AP Photo)

Workers sit next to a building at the Weizmann Institute of Science destroyed by an Iranian missile in Rehovot. (Source: AP Photo)Iran-Israel conflict: A day after President Donald Trump expressed his unhappiness, especially with Israel, for violating the ceasefire he announced on Tuesday morning, a fragile peace seemed to be holding in the Middle East.

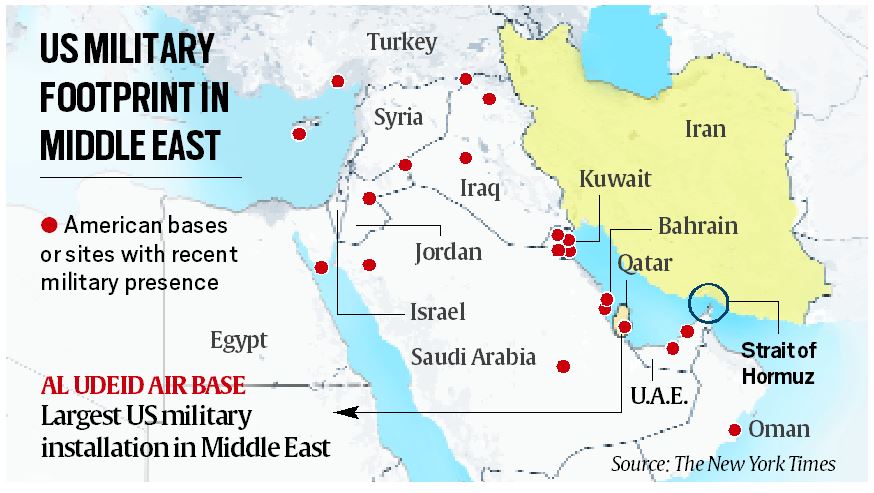

On Monday, Iran launched a missile attack at the US military’s Al-Udeid Air Base in Qatar in retaliation for the American strikes on its nuclear facilities in Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan. No damage was done, and Trump later thanked Iran for providing the US with advance notice of its attack.

Trump subsequently rejected the findings of a preliminary assessment that the US bombs had set back Iran’s nuclear program by only a few months, insisting that it had, in fact, been “obliterated”.

How should the last 24 hours of what Trump has described as the “12-day war” be understood, and what should be expected in the Middle East in the coming days and weeks?

Iran’s calibrated response

Both during and after the Al-Udeid strikes, the Iranian Supreme National Security Council underlined that the attack “did not pose any threat to our friendly and brotherly country, Qatar”, and that the US base was “far from urban facilities and residential areas”.

Almost all Iranian missiles were intercepted, with no American or Qatari casualties reported. Crucially, the Iranian attack was telegraphed to the US “in advance”, was calibrated and evidently symbolic in nature.

For context on this choreography, the American strikes did not eliminate Iran’s enrichment capabilities or destroy its existing stock of enriched uranium.

While the latest estimate by the US Defense Intelligence Agency suggests Iran’s potential nuclear weapons program has been set back only “by months”, Iran has claimed that its 60% enriched stockpiles were withdrawn from Fordow before the US bombs hit.

Arab media reports had suggested earlier that Washington had supplied advance notice of the June 22 strikes, and had communicated privately to Iran that the attacks would be a one-off.

Through the first 10 days of the Israeli attacks that began on June 13, the Iranians consistently maintained two positions — that they were willing to resume nuclear negotiations if Israel ceased its attacks, and that American bases (including those in Arab states) would be hit if the US joined Israel’s aggression.

After the June 22 US attacks, Tehran had to find the optimal point between acting to preserve the credibility of its threats and restraining itself enough to retain space for negotiations — and to recuperate. The latter is especially important given Iran’s worsening economic crisis.

Consequently then, Iran had enough reason to limit its response. Among all Arab states, Qatar was arguably the one where Iran could risk targeting US assets and try to contain the diplomatic fallout.

Qatar, which has positioned itself as a neutral mediator for the region’s many conflicts (including between Israel and Hamas), has long maintained strong ties with Iran. This relationship was among the key reasons why Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and Bahrain imposed an unprecedented blockade on Qatar between 2017 and 2021. The blockade ended two years before the Arab rapprochement with Iran in 2023.

Advance warning by Iran allowed Qatar to shut its airspace an hour before the attacks. And the US military had spent the previous week removing its aircraft from Al-Udeid.

What did not happen

* Despite having issued threats, Tehran refrained from closing the Strait of Hormuz between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, which is vital for both global and Iranian energy needs. Evidently, even a combined US-Israeli attack on Iran did not amount to a dire enough trigger for a blockade.

* Iran’s proxies in the region, nurtured for decades by Tehran, played no part in the retaliation.

THE HOUTHIS of Yemen, who had ended their ceasefire with the US in April, did not resume attacks against American shipping. The Houthis continue to show a marked ability to start or halt attacks on their own terms.

HEZBOLLAH, the Lebanon-based proxy, had refrained from going all-out against Israel even before its capabilities were significantly degraded in September 2024.

Throughout Israel’s war on Gaza, Hezbollah, facing significant internal challenges, engaged only in calibrated rocket and drone attacks, drawing Israeli retaliation at a level it could absorb. Its eventual war with Israel, in which its leader Hassan Nasrallah was killed, was fought on Israel’s terms. And on June 20, Hezbollah’s current chief, Naim Qassem, while expressing strong solidarity with Iran amid Israel’s attacks, committed only to “act as we see fit” — retaining ambiguity.

HASHD-AL-SHAABI: Iranian retaliation was anticipated in Iraq, where the US has bases, and where Iran has cultivated the Hashd as an umbrella proxy group since 2019.

However, Iran did not press this militia into action — a repeat of its strategy of January 2020, when, following the assassination of Maj Gen Qassem Soleimani, the head of the Quds Force, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) launched missiles at US bases at Ain-al-Assad and Erbil, but did not involve the Hashd.

The Americans were told of the strikes in advance, they did not suffer any casualties, and chose not to escalate.

Unlike the bases in Iraq, however, Al-Udeid is the US military’s crown jewel in the Middle East. The 29-year-old self-sufficient base houses 10,000 troops from multiple countries, and is the nerve centre of US operations in the region.

But like in 2020, the US recognised Iran’s need to save face, and refrained from escalating in response.

What now for Middle East

Now that active hostilities have ceased, where does the region stand?

Iran did not fight on its own terms, and it would have liked to avoid the war. This was evidenced by its commitment to resume negotiations, if Israel halted its attacks.

The June 22 strikes were the first ever American military attacks on Iranian soil, but it was Israel which imposed the most substantial costs on Iran by its sustained attacks — decimating the senior leadership of the IRGC and posing an unprecedented threat to the Supreme Leader himself.

However, Iran’s leadership and military could reorganise itself enough to sustain retaliatory missile salvos against Israel, including the use of its advanced solid fuelled ballistic missile, Kheybar Shekan.

For Iran, this was both symbolically and substantially important. Its threshold of success is lower, defined simply by its ability to hit Israel, beating both US air defence units in the region, and Israel’s multi-layered AD systems.

Any bombing campaign, let alone a “one-off” strike, can only delay, not end, Iran’s road to a nuclear weapon — should it seek one. It is this clear inference that has long pushed the US and Europe to seek negotiations with Tehran, despite the severe imbalance in conventional military power.

Unlike the “one-off” operation by the US, Israel’s objectives were maximalist — complete Iranian nuclear dismantlement and regime change. It could achieve neither objective. But it has demonstrated that it can conduct a stand-off war against the Iranian homeland and draw in US military action, even if limited.

This has always been Iran’s worst-case scenario — and the reason it cultivated a regional network of militias as a sub-conventional forward defence strategy.

Iran’s abject economic crisis has only increased the imperative for sanctions relief through negotiations. That would restrict its path to the bomb and demand a modernisation of its conventional capabilities, more so because of the weakness of its proxy groups.

But in the larger scheme of things, this war has likely convinced both Iran and its neighbouring Arab states of the value of nuclear weapons as the ultimate guarantor of security in the long term.

Bashir Ali Abbas is a Senior Research Associate at the Council for Strategic and Defense Research, New Delhi

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05