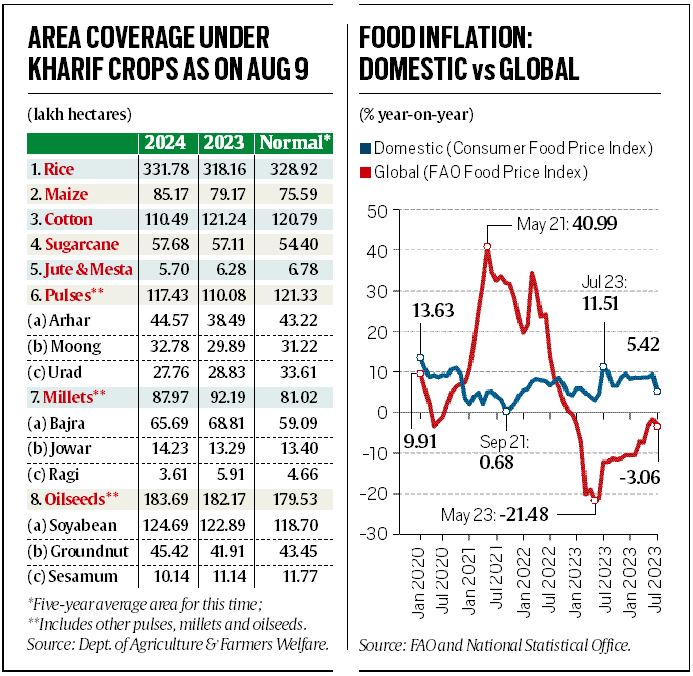

Retail food inflation ruled above 8% for eight straight months from November 2023 to June 2024. That year-on-year increase, in the official consumer food price index (CFPI), fell to 5.4% in July, from 9.4% the month before.

The sharp decline, though, is a statistical illusion, stemming from a high “base” inflation of 11.5% in July 2023. The monthly CFPI rise (July 2024 over June 2024), at 2.8%, translates into an annualised inflation of 33.8%!

Simply put, food inflation remains the economy’s bugbear, eating into household incomes and suppressing spending on other things, besides preventing the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) from cutting its policy interest rates. Given the high share of food in the average Indian’s consumption basket, “the public at large understands inflation more in terms of food inflation…[which also] adversely affects household inflation expectations,” the RBI governor Shaktikanta Das said recently.

Amidst all this, there are at least two reasons for cautious optimism.

Monsoon optimism

The first has to do with the monsoon.

The southwest monsoon set in over Kerala on May 30, two days before schedule. Yet, June as a whole registered 10.9% below the historical long period average (“normal”) rainfall for the month. Rain was subpar everywhere, save the South, Maharashtra (excluding Vidarbha), west Madhya Pradesh and east Rajasthan. It was, perhaps, the residual effect of El Niño that lasted from April-June 2023 to March-May 2024.

But as El Niño – an abnormal warming of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean waters off Ecuador and Peru, generally known to suppress rainfall in India – transitioned into a “neutral” phase, the monsoon revived. July recorded 9% above normal rain.

Story continues below this ad

The current month, too, has seen 15.4% above-normal rainfall so far, taking the cumulative surplus for the season (June-September) to 4.8% as on August 15. The deficiency is now largely confined to the East, and parts of northwest India where farmers have access to irrigation.

The overall good monsoon with well-distributed rainfall has led to higher acreages under most kharif crops this year. Area sown is up for rice, pulses such as arhar (pigeon pea) and moong (green gram), maize, oilseeds (soyabean and groundnut) and sugarcane – relative to both the corresponding period of 2023 and the normal coverage for this time (see table).

Data on food inflation.

Data on food inflation.

Farmers plant more when there is adequate water. They also go for crops whose prices are better or assured. Arhar and maize are now wholesaling at Rs 10,500-11,000 and Rs 2,600-2,700 per quintal respectively, way above their corresponding official minimum support prices (MSP) of Rs 7,550 and Rs 2,225. Not surprising, then, that farmers have aggressively sown both crops – which should also help ease inflation in pulses (arhar dal is retailing at an average of Rs 165/kg, against Rs 140 a year ago and Rs 110 two years ago) and animal proteins (maize is a key poultry and cattle feed ingredient) down the line.

On the other hand, farmers have sown less area under cotton, trading at Rs 7,500-7,600 per quintal in Gujarat’s Rajkot market. That’s just around the MSP of Rs 7,521 for long-staple varieties, when the new crop’s first picking is due only after mid-September. Flat prices, long cropping duration (6-7 months) and risks of insect pest attacks (especially the deadly pink bollworm) have dampened farmers’ enthusiasm in planting cotton. They have switched area this time to groundnut, soyabean and maize (which mature in 3-4 months) or even paddy (where MSP is assured through government procurement).

Low global food prices

Story continues below this ad

Farmer supply response to a good monsoon and high prices apart, there’s a second factor that may reduce inflationary pressures in food.

Global food inflation has been in negative territory since December 2022. The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization’s food price index averaged 120.8 points in July 2024, 3.1% down from its year-ago level. The index – a weighted average of the world prices of a basket of food commodities over a base period value (taken at 100 for 2014-16) – is also 24.7% below its 160.3 points peak scaled in March 2022 following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Even sharper is the cereal price index’s fall, from 173.5 points in May 2022 to 110.8 points now.

While global and domestic food inflation have been moving in opposite directions in recent times (see chart), low international prices, however, make imports more feasible. Russian wheat, for instance, is currently being exported at about $220 per tonne free-on-board (i.e. from the port of origin), compared to $250-plus a year back and $395-405 in March-May 2022. Adding ocean freight and other charges of $45-50 would take the landed cost of imported wheat in India to $265-270 per tonne or Rs 2,225-2,270/quintal. That’s below the ruling market price of Rs 2,600 in Delhi and even the MSP of Rs 2,275.

The point to note is that benign international prices – a contrast to the situation post the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war – not only lessen the risk of “imported inflation”, as it happened particularly in vegetable oils from late-2020 to 2022. They can put a lid on domestic prices, like with wheat if imports are allowed through lowering of duty (from the present 40%).

Going forward

Story continues below this ad

Wheat stocks in government warehouses, at 268.12 lakh tonnes (lt) on August 1, were the third lowest for this date after 2022 (266.45 lt) and 2008 (243.80 lt). However, the rice stocks (including the grain equivalent from un-milled paddy) of 454.83 lt were the highest ever for the same date.

The prospects of a monsoon-aided bumper kharif crop should enable relaxation of the export ban/restrictions on non-basmati rice as well as sugar, along with the lifting of stockholding limits on pulses applicable to traders, retailers and dal millers.

Above-average rains so far have filled up the country’s major reservoirs to nearly 65% of their total storage capacity (as against last year’s 61% and the 10-year normal of 54% for this time) and also recharged groundwater tables. That – plus the high probability of the emergence of La Niña (El Niño’s “cool cousin”, associated with robust rainfall activity in India) during September-November and persisting through the winter-spring months – is encouraging for the ensuing rabi cropping season too.

But all this optimism has to be tempered by the fact that the kharif crop’s harvesting is at least a month away, while not before March-end for wheat and other rabi crops. The uncertainty over food inflation will continue for some time till then.

Data on food inflation.

Data on food inflation.