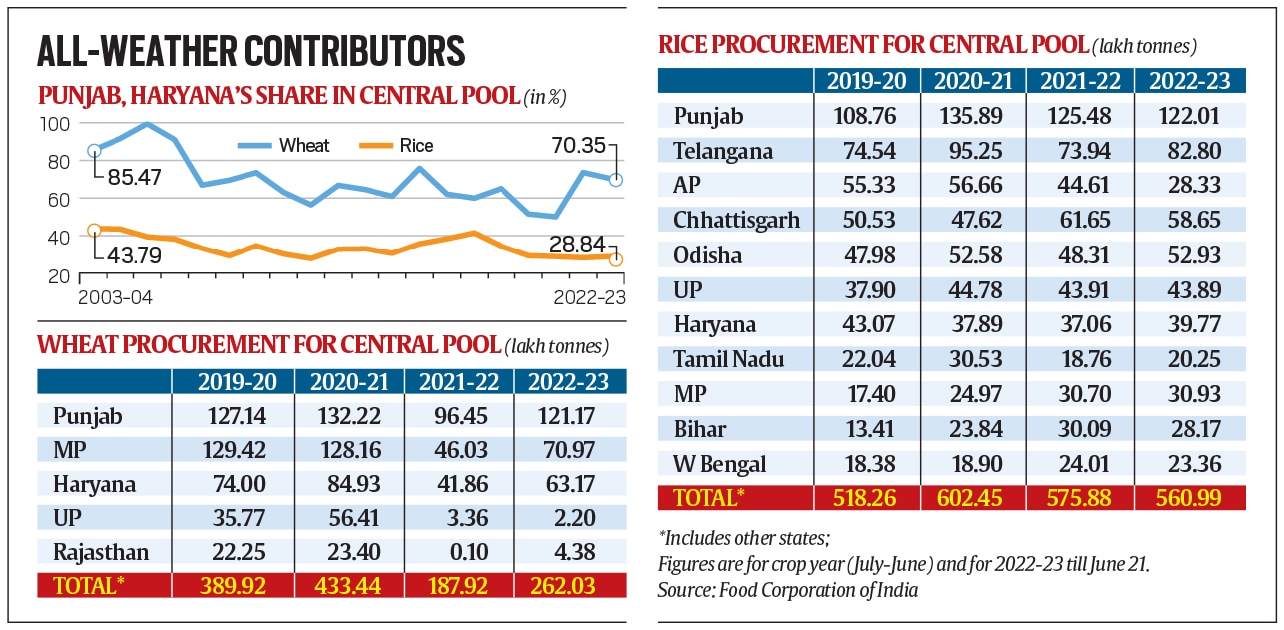

Over the last two decades though, the two states’ combined share in total wheat procurement for the Central foodgrain pool has fallen from 90% or more, to hardly 70%. It’s been more, from 43-44% to 28-29%, for rice (chart).

The diversification of procurement – traditionally concentrated in Punjab and Haryana for wheat and in the two, plus Andhra Pradesh (AP) and Tamil Nadu, for rice – has come on the back of the Green Revolution (the cultivation of high-yielding semi-dwarf varieties) spreading to more states and their governments also establishing infrastructure for purchase of grain at minimum support prices (MSP) from farmers.

Story continues below this ad

Take wheat, where Madhya Pradesh (MP) briefly overtook Punjab as the top contributor to the Central pool in 2019-20: That was the crop harvested and marketed during April-June 2020 just after the first Covid lockdown. In rice, Telangana has emerged as a clear No. 2 behind Punjab, with Chhattisgarh, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh (UP), too, making impressive strides over the past decade, if not less (see tables).

But one bad monsoon or poor crop can make a difference

This has already been seen in wheat. The last two crops weren’t all that great, owing to unseasonal temperature surge in March 2022 and heavy rain in March 2023, both at the time of grain-filling. Low production, in combination with high (above MSP) market prices, led to wheat procurement from MP plunging from almost 13 million tonnes (mt) to 4.6 mt in 2021-22. Although it rose to 7.1 mt in 2022-23, MP has dropped way behind Punjab. Even sharper has been the slide in procurement from UP and Rajasthan.

Simply put, the contribution of most states to wheat procurement has tended to be high largely in “fair-weather” years delivering excellent harvests, such as 2019-20 and 2020-21. During these two years, the combined share of Punjab and Haryana in procurement declined to 50-51%. But that has gone up in the last two years to 70-74%, reinforcing their status as reliable, “all-weather” contributors to national food security.

Story continues below this ad

The above story may play out even more this year

The reason for it is El Niño. Sea surface temperatures across the east-central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean off the coasts of Ecuador and Peru are already ruling above average. These temperature anomalies, consistent with “weak” El Niño conditions now, are expected to “gradually strengthen” into the winter through December-February, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

El Niño, going by historical data, has been associated with monsoon failures in India. Thus, 2014, 2015 and 2018 recorded subnormal rainfall – and all three were El Niño years. On the other hand, the country enjoyed four consecutive years of good monsoon from 2019 to 2022. This period saw no El Niño in 2019, even as it had one of the longer ever La Niña event, lasting from July-September 2020 to December-February 2022-23. The latter – El Niño’s opposite, involving an abnormal cooling of the central and eastern tropical Pacific waters – usually brings copious rain to India, as it happened during the most recent episode (https://shorturl.at/imtMW).

During the current southwest monsoon season (June-September), the country has so far received rainfall 27.7% below the long-period average for June 1-25. Most global weather agencies had previously forecast El Niño’s to develop only towards August or later. Its earlier-than-anticipated arrival, and sudden gain in strength between March and May, has cast a shadow over rain in the remaining part of the season.

Story continues below this ad

The immediate impact of a subnormal monsoon would be on the kharif crops, the sowings of which have barely taken off. Rice may bear the brunt, being highly water-intensive and requiring at least 25 irrigations in the absence of rain. Moreover, if El Niño is going to get stronger, the impact could extend to the rabi (winter-spring) crops. These, particularly wheat, are grown using groundwater and dam reservoirs that are recharged/refilled during the monsoon. A subnormal monsoon can, in other words, hit both rice and wheat production.

The saviour states

That’s where Punjab and Haryana come in. They are states whose farmers have assured access to irrigation. Punjab alone cultivated paddy (rice with husk) on 31.67 lakh hectares (lh) in 2022-23, including 4.94 lh under basmati varieties.

Gurvinder Singh, director of Punjab’s agriculture department, sees no reduction in rice area this year. If at all, it might increase due to diversion of some area from cotton, which has become vulnerable to whitefly and pink bollworm pest attacks, apart from fetching lower prices compared to last year. In paddy, there’s no price risk, courtesy of guaranteed MSP procurement.

“Even in the event of a poor monsoon, our farmers would be able to safeguard their crop, thanks to the 15 lakh electric tube-wells in the state,” Singh said. The Punjab government is supplying eight hours of uninterrupted free power daily to run these tube-wells during the four-month paddy season (from transplanting to harvesting), starting June 10.

Story continues below this ad

An agriculture department official claimed that paddy yields in Punjab actually tend to go up during low rainfall years. That’s because farmers then rely solely on groundwater and irrigate their fields accordingly. They are more worried about the monsoon season prolonging and causing rain towards the harvesting period. Even in wheat, the crop yield losses of the last two years have come from temperature spikes and too much, as opposed to less, rain.

Policymakers and economists have, for long, advocated weaning away Punjab and Haryana farmers from rice and also cutting back wheat acreage. But today, in a scenario of precariously balanced government stocks and global rice prices soaring to their highest since November 2011, it’s these very farmers who may play saviour yet again.