India’s production of cereal grains has gone up over 1.5 times in the last two decades, according to the agriculture ministry.

But a rising share of that is going not for direct human consumption, but for use in processed form (as bread, biscuits, cakes, noodles, vermicelli, flakes, pizza base, etc) or for making animal feed, starch, potable liquor and ethanol fuel. This is evidenced by data from official household consumption expenditure surveys (HCES).

The National Sample Survey Office’s latest HCES report reveals a steady decline in the quantity of cereals consumed by an average person per month – from 12.72 kg to 9.61 kg in rural and from 10.42 kg to 8.05 kg in urban India – between 1999-2000 and 2022-23. The overall per capita drop, using weights based on the rural-urban distribution of the HCES sample households, has been from 11.78 to 8.97 kg during this period.

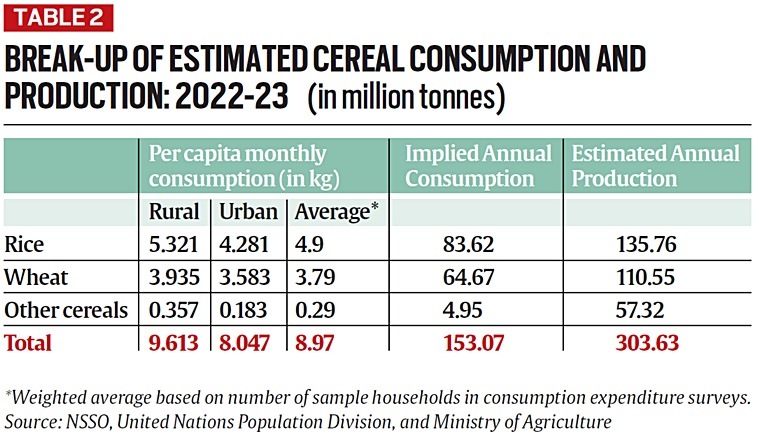

Multiplying the above weighted average over 12 months with the country’s population yields the total annual consumption of cereals by Indian households, in direct or processed-at-home form. This, as table 1 shows, has registered only a mild jump, from 148.4 million tonnes (mt) in 1999-2000 to 153.1 mt in 2022-23 and actually falling over the last decade.

While direct household consumption has stagnated, even dipped, this isn’t so with production, which has significantly increased from 196.4 mt in 1999-2000 to 303.6 mt in 2022-23. The gap between officially estimated cereal production and HCES-based household consumption, too, has widened from hardly 48 mt in 1999-2000 and 29.5 mt in 2004-05 to nearly 151 mt in 2022-23.

Where is this excess production going?

Part of it is getting exported, i.e. going out of the country. In 2021-22 (April-March), India shipped out a record 32.3 mt of cereals, including 21.2 mt rice, 7.2 mt wheat and 3.9 mt other grains (mainly maize). Even in 2022-23, cereal exports totaled 30.7 mt: 22.3 mt of rice, 4.7 mt of wheat and 3.6 mt of other grains.

The 31-32 mt of exports would, however, have accounted for just a fifth of the 150 mt-plus difference between production and direct household consumption of cereals in 2022-23.

Story continues below this ad

A second source of difference would be cereals consumed by households in processed form – bread, biscuits, noodles, etc. Even assuming this to be 25% over and above direct cereal consumption, it comes to an additional 38 mt or so.

A third source is cereal grain used for manufacture of feed or industrial starch. The agriculture ministry has pegged India’s maize production in 2022-23 at 38.1 mt. The bulk of it – 90%, if not more – would have been used as the primary energy ingredient in poultry, livestock and aqua feed or for wet-milling and conversion into starch, which has applications in the paper, textile, pharmaceutical, food and beverage industries.

Table 2 shows the production of “other cereals” – maize, barley and millets such as bajra (pearl millet), jowar (sorghum) and ragi (finger millet) – at 57.3 mt. As against this, the direct consumption of these coarse grains in Indian households worked out to below 5 mt. Much of their consumption would be in indirect form – as milk, egg and meat after being fed to cows, buffaloes and layer/broiler poultry birds.

Feed and starch manufacturing apart, cereal grains are also fermented into alcohol (after milling and converting their starch into sucrose and simpler sugars) and further distilled into about 94% rectified/industrial spirit or 99.9% ethanol.

Story continues below this ad

In recent times, many sugar mills have installed multi-feed distilleries, enabling them to run on cane molasses or juice/syrup during the crushing season (November-April) and grain (broken/damaged rice, maize and millets) in the off-season (May-October). This has received an impetus from the government’s programme for blending up to 20% of ethanol in petrol.

In other words, cereals are today not just food and feed, but also fuel grains.

The unexplained surplus

Adding exports of 32 mt, usage in processed food form (38 mt) and diversion for feed, starch making and fermentation purposes (50-55 mt) — these are very rough estimates — to direct household consumption of 150-155 mt will take the total yearly demand for cereals to 275-280 mt at best.

That’s way below the estimated 300 mt-plus domestic cereal output. The difference is the surplus grain being mopped up by government agencies and accumulated in the Food Corporation of India’s warehouses. In the 2022-23 crop year (July-June), around 56.9 mt of rice and 26.2 mt of wheat got procured, more than the total annual cereal requirement of 59-60 mt for the public distribution system (PDS).

Story continues below this ad

Under the National Food Security Act, some 813.5 million persons are being given 5 kg of wheat or rice per month through the PDS free of cost (the issue price was Rs 2 and Rs 3/kg for the two respectively till December 2022). The 5 kg entitlement for these beneficiaries covers more than half of the monthly per capita cereal consumption of 9.61 kg in rural and 8.05 kg in urban India as per the HCES for 2022-23.

If the agriculture ministry’s cereal output estimates are right, the country is producing at least 25 mt of excess grain every year, thereby exerting downward pressure on market prices, if not adding to government stocks.

But given the recent experience of high cereal inflation (8.69% year-on-year in May), notwithstanding ban/restrictions on exports, and depleting stocks in government warehouses (16-year-low for wheat on June 1), questions can be raised on the veracity of the official production estimates themselves.