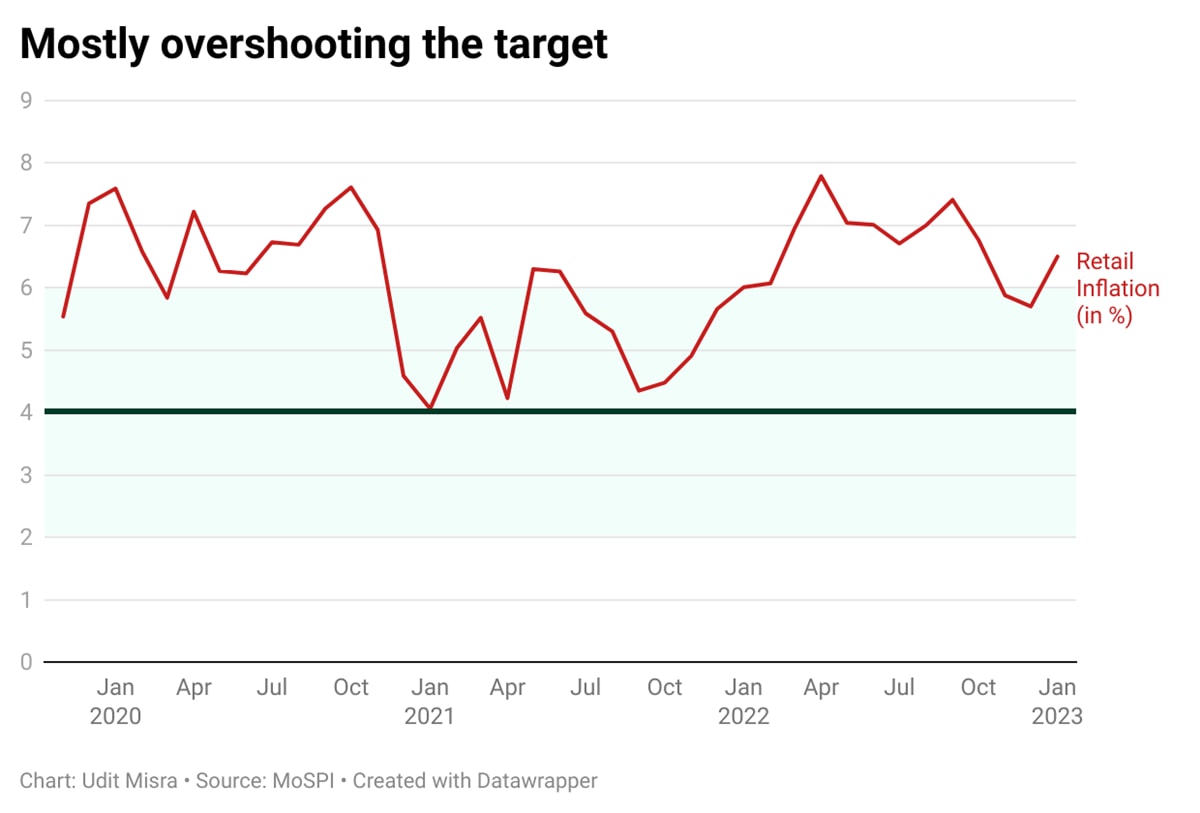

At 5.30 pm Monday, the government will release the retail inflation data for the month of February. Ordinarily a single month’s inflation data would not be any more (or any less) important that any other month but, given the fact that India’s monetary policy is balanced on a knife-edge at present, February’s data has acquired a rather exalted significance.

This has resulted in RBI losing policy credibility to some extent. For instance, many wonder whether 5% or 6% is the effective target for the RBI instead of 4%.

“In the second half of 2021-22, monetary policy was complacent about inflation, and we are paying the price for that in terms of unacceptably high inflation in 2022-23,” said Prof. Jayanth R. Varma, one of three government-nominated members of the MPC, according to the minutes of the MPC’s February meeting.

Since May 2022, however, the RBI has been rapidly raising interest rates in a bid to contain high inflation. As a result, the repo rate — or the interest rate that the RBI charges banks when it lends money to them — has gone up by 250 basis points since May. It was 4% in May and stands at 6.5% today. Since repo is the rate at which banks get money, a hike in repo implies higher interest rates for all concerned in the Indian economy.

Story continues below this ad

Growth vs Inflation

While on paper the RBI’s central responsibility is to maintain price stability, it often also concerns itself with boosting economic growth. It can be argued that over the past four years, the RBI has been more concerned about growth than inflation.

To be sure, these two concerns pull the RBI in opposite directions. Boosting economic growth requires maintaining low interest rates while containing inflation demands high interest rates.

After retail inflation hit an eight-year high in April 2022, however, the RBI has prioritised containing inflation. But doing this is starting to hurt growth. In fact, the MPC’s last two decisions — in December 2022 and February 2023 — have been split votes.

Here’s the follow up on what Prof Varma said in February: “In the second half of 2022-23, monetary policy has, in my view, become complacent about growth, and I fervently hope that we do not pay the price for this in terms of unacceptably low growth in 2023-24.”

Story continues below this ad

The dilemma before the MPC

The MPC, which deliberates once every two months, is next scheduled to meet in April. The last data point on inflation before the April meet will be the February inflation due to be released on Monday.

If inflation is again above 6% yet again — most expect inflation to be 6.4% — then it will make the job of the RBI very difficult.

Here’s how.

If both headline inflation, as well as core inflation (which strips the effect of food and fuel prices), are above the 6% mark then — given RBI’s recent history of failings in containing inflation — can any central bank announce that it finds enough evidence that inflation has subsided and that it is time to hit the pause button?

Chances of this happening are low.

That, in turn, implies another 25 basis point increase in repo rate in April.

Story continues below this ad

However, at least two MPC members — Prof Varma and Prof Ashima Goyal — are quite concerned about RBI’s monetary tightening choking India’s growth recovery.

“Excessive front-loading of rate hikes carries the risk of over-shooting that is best avoided for compelling reasons in the Indian context,” stated Goyal according to February MPC minutes. She gave several reasons why RBI should not go overboard with interest rate hikes.

“First, raising real policy rates to reduce demand has a stronger effect on growth than it does on inflation,” she states. The real policy rate is calculated by taking the repo rate (at present at 6.5%) and subtracting the inflation as it is expected to be a year ahead (5.3%). Her point is that every additional hike in repo rate above the 6.25% level will drag down growth far more than dragging down inflation. As such, all rate hikes above 6.25% are likely to be counterproductive.

She also pointed to the fact that there are “lags in monetary transmission”. That is to say that it takes a few months, sometimes quarters, before a hike in repo rate results in higher interest rates across the board in the economy and in denting consumption and investment demand. As such, the MPC should wait for a while to let past repo rate hikes take effect.

Story continues below this ad

Lastly, she warned: “If a sharp rise in the real policy rate, substantially above unity (read 1%) , triggers a shift to a lower trend of private investment and growth, then the sacrifice ratio of disinflation can be very high, as it was in the 2010s”.

Varma has been voicing these very same concerns for much longer.

According to the minutes of the December MPC meeting, Varma stated: “During the pandemic, exports and government spending were the two growth engines that counteracted the headwinds confronting the Indian economy. Of these, the global slowdown has already led to the export growth engine grinding to a halt. Fiscal constraints limit the ability of government spending to hold up the economy on its own. Private investment is unlikely to be able to pick up the slack.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that concerns about future growth prospects are deterring capital investment even by companies that have reached more than 80% capacity utilization. That leaves only private consumption which has remained buoyant, but it remains to be seen how much of this is due to pent up demand which could dissipate over the coming months. All of this means that economic growth is now extremely fragile and definitely not robust enough to withstand excessive monetary tightening.”

Story continues below this ad

Presuming that February’s retail inflation will hover around 6.4%, should the MPC pause monetary tightening to protect India’s growth or should it continue raising rates unless it sees credible signs that inflation has simmered down? Share your views and queries at udit.misra@expressindia.com

Until next week,

Udit

Chart: Since November 2019, inflation rate has rarely touched 4%

Chart: Since November 2019, inflation rate has rarely touched 4%