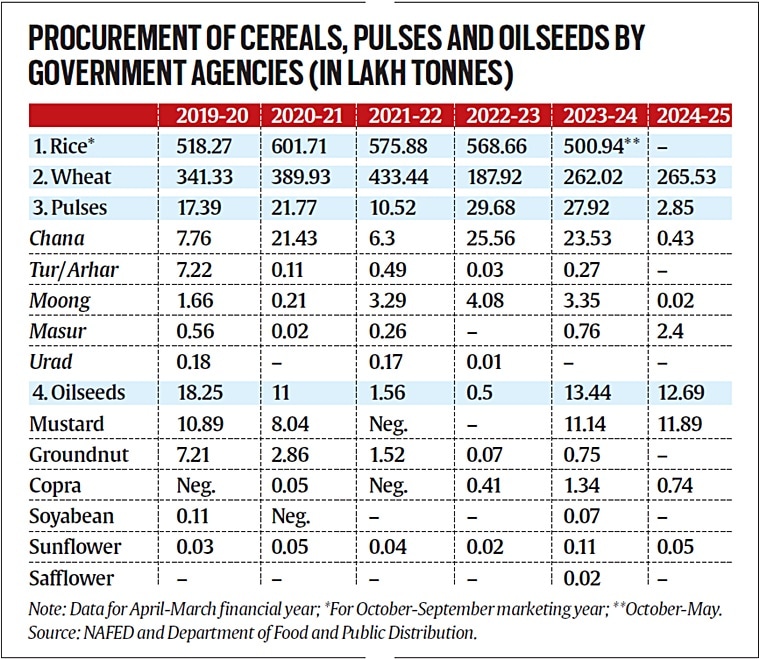

These rates would probably have been higher, but for the sales from buffer stocks, especially of wheat and chana (chickpea), built by government agencies during surplus production years.

Take wheat. In 2022-23 (April-March), 34.82 lakh tonnes (lt) of the cereal was offloaded from the Food Corporation of India’s (FCI) stocks in the open market to boost supplies. Such sales, mainly to flour millers at market prices determined through e-auctions, rose to a record 100.88 lt in the following fiscal. That included 6.73 lt processed into flour and sold under the ‘Bharat Atta’ brand at a maximum retail price of Rs 27.5/kg.

The FCI’s open market sale scheme brought down retail inflation in cereals and wheat, from their respective highs of 16.73% and 25.37% in February 2023 to 8.69% and 6.53% in May 2024. While not-so-good crops in the last three years had depleted wheat stocks in government warehouses from their peak of 603.56 lt on July 1, 2021 to 285.10 lt and 301.45 lt on the same date of 2022 and 2023, these were enough for the FCI’s open market intervention.

Prices of pulses have been on fire, with retail inflation in double digits since June 2023.

According to the department of consumer affairs, the all-India modal (most-quoted) retail price of split chana dal currently stands at Rs 90 per kg, as against Rs 70 a year ago. Prices of tur/arhar (pigeon pea) have risen even more (Rs 120 to Rs 170), while urad (black gram) and moong (green gram) have seen a lesser rise (Rs 110 to Rs 120), and prices for masur (red lentil) have been flat (Rs 100/kg).

But things would have been worse had the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) not bought large quantities of the bumper 2021-22 and 2022-23 chana crops. These purchases, during April-June of 2022 and 2023 respectively (also the marketing season for wheat, mustard, masur and other rabi winter-spring crops), amounted to 25.56 lt and 23.53 lt. They were made at the government’s declared minimum support price (MSP) of Rs 5,230 and Rs 5,335 per quintal for the two crop years, when chana was wholesaling at Rs 4,400-4,800 in the agricultural mandis of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh.

Story continues below this ad

In the current season, with open market prices Rs 6,000 or more, way above the MSP of Rs 5,440/quintal, NAFED could procure just over 43,000 tonnes of chana. However, it had stocks of 37.21 lt on July 1, 2023 accumulated from the last two years’ procurement. These stocks proved useful in checking inflation in pulses, resulting from an El Niño-induced patchy monsoon and poor 2023-24 crop.

“Our procurement operations enabled chana farmers to reap the benefits of MSP when open market prices were low, and, more recently, insulate consumers from dal inflation,” S K Singh, additional managing director of NAFED, told The Indian Express.

Since July 2023, NAFED has sold 14.06 lt of chana through open market e-auctions, 16.09 lt as ‘Bharat Dal’ at Rs 60/kg, 2.91 lt as discounted supplies to state governments and 0.57 lt as allocation to the armed forces. In the process, its stocks have come down to 4.01 lt now.

The case for a buffer policy

Overall CPI inflation, at 4.75% year-on-year in May, was the lowest in 12 months. It would have been lower had retail food inflation not stayed elevated at 8.69%.

Story continues below this ad

The inherently volatility and unpredictability of food prices, exacerbated by climate change — fewer rainy days and extended dry spells, interspersed with intense precipitation, and also shorter winters and heat waves — has made it difficult for the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to consider any monetary easing or cutting interest rates. The government, too, is forced to resort to undesirable measures such as restricting exports, or imposing produce stock limits on traders and processors.

One possible way out of the conundrum would be to build a buffer stock of all essential food items, by procuring these from farmers during years of surplus production, and offloading the same in times of crop failures to moderate market prices.

The accompanying table shows that MSP procurement by government agencies is confined to rice, wheat and a few pulses (chana, tur/arhar, moong and masur) and oilseeds (mustard, groundnut and copra). The latter procurement, unlike for rice and wheat, also happens only in some years.

There’s scope to not only expand procurement of pulses and oilseeds, but extend it to staple vegetables and even skimmed milk powder (SMP). The onion, potato and tomato procured can be stored in dehydrated/processed form such as paste, flakes and puree for sales to hotels, restaurants, canteens, and other institutional buyers. This would ensure that both households and bulk buyers do not compete to drive up prices during shortages.

Story continues below this ad