From Aithihyamala to Lokah: Recasting Kerala’s Folklore

By weaving Neeli, Kathanar, Chathan, and the Odiyan into a shared canvas, Lokah doesn’t close their tales. It reopens them, showing how folklore can be both an archive and a battlefield.

Kalyani Priyadarsan as Neeli, Tovino Thomas as Michael, one of the Chathans, and Dulquer Salmaan as Charlie, the Odiyan in Lokah Chapter One: Chandra. (DQ Wayfarer Films)

Kalyani Priyadarsan as Neeli, Tovino Thomas as Michael, one of the Chathans, and Dulquer Salmaan as Charlie, the Odiyan in Lokah Chapter One: Chandra. (DQ Wayfarer Films)Myth and reality have long coexisted in the villages and forests of Kerala. It is in this liminal space that Dominic Arun’s Lokah Chapter 1: Chandra rewrites some of Kerala’s most enduring legends, including Kalliyankattu Neeli, Kadamattathu Kathanar, the Odiyan, and the Chathan.

These figures, immortalised in Kerala’s oral tradition and recorded in Kottarathil Shankunni’s Aithihyamala, reveal a society’s fears, desires, and hierarchies. The 2025 Malayalam film weaves old stories into a modern narrative, where Malayali myths meet a Marvel-like world setting.

In Lokah, Neeli steps out of the shadow of male desire and punishment, Kathanar negotiates authority differently, Odiyan takes on a ninja-like guise, and the mischievous Chathan teases a larger supernatural architecture. The movie reminds audiences that these myths are living, evolving narratives.

View this post on Instagram

Kalliyankattu Neeli: Fury forged in injustice

A yakshi is a female spirit, a woman who met a violent death, who rose from death for vengeance. Yakshis are described as women possessing an ethereal beauty with a fatal allure, causing them to be both feared and revered. Most yakshis are described as vengeful vampire-like blood-suckers, punishing men who are lured in by their beauty.

The legend of Kalliyankattu Neeli, probably Kerala’s most famous yakshi, is rooted in betrayal. The Aithihyamala narrates the tale of Alli, a wealthy devadasi’s daughter, whose life was bound to the temple she served, and circumscribed by ritual and caste. Defying her mother, she courts and eventually marries Nambi, a Brahmin priest, only to be struck dead by his fatal deception, as he killed her for her jewellery. Her dying rage was so profound that it transformed her into a Yakshi.

Nambi’s fate has been described variously: in some narratives, Neeli kills Nambi, in some, he dies of a snakebite, and in others, Neeli avenges her own death in a rebirth as the yakshi. Neeli is, however, described as the dreadful presence in Kalliyankadu, the forest where she was killed, sucking blood off men who travel alone, and at night.

The basic structure of the legend of Neeli has not changed, with some narratives placing her as early as the Chola era and as late as the 15th-16th centuries.

The folklore strongly positions Neeli’s monstrosity within caste hierarchies. Alli’s defiance of caste boundaries becomes grounds for her brutal end and stresses the righteousness of her vengeance, making her terrifying.

In Lokah, the familiar legend is not simply retold but upended. Neeli is now a ten-year-old tribal girl whose entire community was massacred by an upper-caste king for defying the codes of untouchability. What was once framed as a woman’s vengeance within the closed world of temple and caste privilege is reimagined as a parable of systemic oppression, her fury no longer personal but collective.

Kadamattathu Kathanar: The priest who dared the supernatural

In a marked contrast to Neeli’s story, the Kadamattathu Kathanar legend is rooted in miracles and sorcery. According to Aithihyamala, the kathanar was once an orphaned boy, Poulose, who grew up in dire poverty before being sheltered by the Syrian Christian priest (referred to in some accounts as Mar Abo, a historical Persian Bishop) of the Kadamattom church, near present-day Muvattupuzha.

As a seminarian, Poulose once wandered into a nearby forest in search of a cow, and was captured by tribal sorcerers. After concluding Poulose’s lack of mal-intent to them, they welcomed him to the fold and taught him the secrets of mantravadam – spells, incantations and the art of commanding spirits. Armed with this knowledge, he ascended to become the parish priest and was much sought for his knowledge of sorcery after as the Kadamattathu Kathanar (The Priest of Kadamattom).

Some versions of the Neeli legend have the dreaded yakshi crossing paths with the Kathanar, with the sorcerer-priest emerging victorious. In these versions, the villagers seek his aid, and he subdues her with his incantations and binds her to a tree, a symbolic act that brings her fury under ritual control.

In some tellings, she is forced into reluctant service at his command. In others, she’s deified, with the Christian priest asking people to worship her. In either case, the narrative resolves by curbing her agency and placing her within the orbit of priestly, male authority.

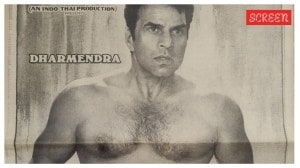

Sunny Wayn as Kadamattathu Kathanar in Lokah (DQ Wayfarer Films)

Sunny Wayn as Kadamattathu Kathanar in Lokah (DQ Wayfarer Films)

Lokah reimagines this dynamic altogether. Here, Kathanar is no longer the patriarchal figure of faith who restrains Neeli, but a collaborator who recognises her strength. What was once a tale about disciplining female rage here becomes a story of camaraderie. Kathanar, who is aware of Neeli’s superhuman capabilities, asks her for a favour.

Chathan: Mischief, magic, and moral lessons

Chathan, comparable to an imp, plays with mischief, morality, and magic. Unlike the terrifying yakshi or the austere Kathanar, the chathan’s power is ambiguous: he can protect a devotee or punish the careless, often in ways that are cryptic, ironic, or humorous.

In Aithihyamala, the chathan myth occupies a special space. Born from Shiva and Vishnumaya, the half-man, half-woman manifestation of Vishnu, the 390-strong chathan fraternity embodies mischief, cunning, and moral ambiguity. They act to punish greed, uphold justice, and sometimes, simply because they’re told to. Their agency was mediated by a Brahmin sorcerer family, Avanangattu, who took offerings from those who needed favours.

A chathan was not divine in the classical sense, but he was an instrument of power, summoned to serve the interests of patrons. Savarna families could use them to secure favours, manipulate rivals, or assert dominance, rendering Chathan a servile force that is never given free will.

Lokah shows us one chathan, played by Tovino Thomas, and retains the spirit’s mischievousness without referring to the Brahmin intermediaries. The larger fraternity is teased in the cliffhanger, acknowledging the folklore’s scope without overwhelming the narrative, resulting in a chathan both friendly and contemporary. He retains the wit and ethical ambiguity of the original myths but operates freely, aiding those tormented by evil powers and correcting wrongs.

Odiyan: Shadows, survival and shapeshifting

Odiyan, or the breaker occupies the darkest corners of Kerala folklore. Born into Dalit communities, they are shape-shifters by night, warriors by compulsion. British records and oral accounts alike note their fearsome reputation. Odiyans were commissioned hitmen, bound not by morality but by caste hierarchies that dictated obedience.

Deprived of land and authority, they wielded a lethal skill that made them scary even as they served. Their shapeshifting, a core of odi vidya, was almost flawless: almost. Subtle defects in their animal forms betrayed them, a reminder that even magic has its limits. Hence, they weaponised the lethal darkness of the nights, hiding behind bushes for their targets to approach.

The myths’ moral ambiguity deepens with tales of Malabar’s odiyans committing heinous acts, including killing pregnant women to harvest the mystical fluids required for transformation, casting them as morally grey forces, neither wholly evil nor heroic, but compelled agents of survival under systemic oppression.

Lokah translates this complex folklore into a cinematic impression. Dulquer Salman’s odiyan appears as a ninja-like, merciless swordsman. The film foregrounds his lethal efficiency, echoing historical truths while compressing centuries of layered fear and power into superhuman capabilities. But even in a cameo, the odiyan resonates with Kerala’s shadowed margins through his silence and loneliness. He only shares a word with his victims and is only friends with those similarly bound, like Tovino’s Chathan.

Opening the mythic horizon

Lokah reminds us that Kerala’s myths were never innocent stories. They carried the weight of caste, gender, and power.

By weaving Neeli, Kathanar, Chathan, and the Odiyan into a shared canvas, the film doesn’t close their tales. It reopens them, showing how folklore can be both an archive and a battlefield.

What emerges is an invitation to read these legends not as finished tales, but as negotiations that continue in the present.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05