What makes Hurricane Hilary ‘unprecedented’

As Mexico and Southern California brace for the never-seen-before storm, a look at what makes hurricanes over the US west coast so rare, and how global warming is changing things.

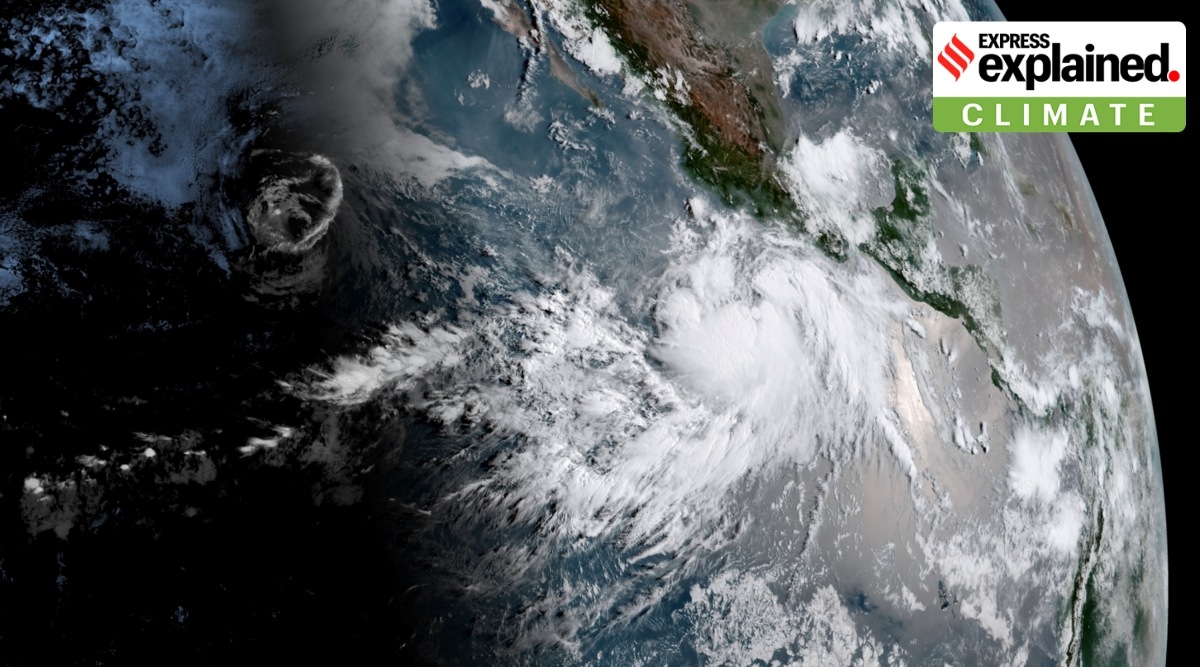

Hurricane Hilary off the coast of Mexico on Wednesday, August 16, 2023. Since the time of the photo, the storm has moved closer to the coast and is expected to make landfall early morning on Sunday (Mexico time). (Photo: NOAA via The New York Times)

Hurricane Hilary off the coast of Mexico on Wednesday, August 16, 2023. Since the time of the photo, the storm has moved closer to the coast and is expected to make landfall early morning on Sunday (Mexico time). (Photo: NOAA via The New York Times) The United States sees its fair share of hurricanes. As per the country’s National Weather Service (NWS), in an average 3-year period, roughly five hurricanes strike the US coastline – but never in the west coast.

This is why Hurricane Hilary, which is currently racing towards Southern California and Mexico, is so out of the ordinary. Though California, in the past, has felt the effects of hurricanes, they typically remain well offshore and subside to become tropical storms by the time they hit they make landfall.

.@NWS is carefully tracking Hurricane #Hilary and the dangerous weather it’s expected to bring to Mexico and the southwestern U.S. Take this storm seriously! Check https://t.co/RzyiIU9fB0 and https://t.co/mhjKxR0cWQ for the latest. pic.twitter.com/MI0rVG7A9c

— NWS Director (@NWSDirector) August 18, 2023

And even these tropical storms are rare. Last year’s Hurricane Kay was the first tropical storm to impact California in a quarter of a century, and it lost most of its force by the time it hit the coast. Prior to that, Hurricane Nora moved over Southern California as a tropical storm in 1997.

As per a 2004 report by the American Meteorological Society, the only tropical storm with hurricane-force winds believed to have hit Southern California came in October 1858, with San Diego bearing its brunt.

The image shows the estimated path of the storm and an approximate timeline. (Source: National Hurricane Center/ NOAA)

The image shows the estimated path of the storm and an approximate timeline. (Source: National Hurricane Center/ NOAA)

“It is rare — indeed nearly unprecedented in the modern record — to have a tropical system like this move through Southern California,” Greg Postel, a hurricane and storm specialist at the Weather Channel, told CBS News.

A race to be ready

Unlike states like Florida, Louisiana and Texas on the Gulf of Mexico, which have learnt over the years on how to survive hurricanes, for Californians and Mexicans in the west, it is a novel, terrifying, experience.

As per latest estimates, the hurricane will make landfall in the Baja peninsula in Mexico, roughly 330 km south of the port of Ensenada. It will move north from there, bringing record rainfall and extremely strong winds.

Tijuana, a sprawling border metropolis of 1.9 million people in Mexico, is at risk of landslides and flooding, because of its hilly terrain, extremely high density of population and poor quality of housing and infrastructure. Mexico has mobilised over 18,000 troops in anticipation of the storm.

Even if Hurricane Hilary loses some of its force by the time it touches Southern California, its impact may be deadly.

The image shows the probable windspeeds the hurricane is likely to hit. (National Hurricane Center/NOAA)

The image shows the probable windspeeds the hurricane is likely to hit. (National Hurricane Center/NOAA)

“Two to three inches of rainfall in Southern California is unheard of” for this time of year, Kristen Corbosiero, a University of Albany atmospheric scientist who specialises in Pacific hurricanes, told AP. “That’s a whole summer and fall amount of rain coming in probably six to 12 hours.”

Communications are anticipated to be cut and power supply lost. People have been urged by authorities to stock up essentials, keep their generators fuelled and fill up sandbags to cover windows.

Why this is so rare

The primary reason why the Pacific coast seldom sees such tropical storms and hurricanes is the nature of the ocean itself. As per NWS, the first condition for the formation of hurricanes is that ocean waters must be above 26 degrees Celsius. Below this threshold temperature, hurricanes will not form or will weaken rapidly once they move over water below this threshold.

Major ocean currents. Blue arrows show cold currents whereas red arrows show warm currents. (Wikimedia Commons)

Major ocean currents. Blue arrows show cold currents whereas red arrows show warm currents. (Wikimedia Commons)

While high temperatures are common during hurricane season along the US east coast, the west coast is much colder. In the Atlantic, warm, equatorial waters are transported north to higher latitudes along the US coast via the Gulf Stream but along the west coast, in the Pacific, cold current steers colder water from higher latitudes toward equatorial regions. This makes hurricanes highly unlikely.

Another factor is the vertical wind shear — a term used to describe the change in wind speed as one travels up from the Earth’s surface — especially in the upper level of the atmosphere. It is an important ingredient in formation of hurricanes as they can extend up to 16 km into the atmosphere. Hurricanes can’t emerge if the upper level winds are strong as they “destroy the storms structure by displacing the warm temperatures above the eye and limiting the vertical accent of air parcels,” according to the NWS. Usually, wind shear in the eastern Pacific is much stronger than the Gulf of Mexico, causing less frequent hurricanes along the western coast.

Lastly, the rarity of west coast hurricanes is the influence of wind steering patterns. Trade winds play a crucial role in directing hurricanes towards the east coast. The same winds divert them away from the west coast. Hurricanes originating in the eastern Pacific, often near the central Mexico coastline, generally follow a west-northwest trajectory that take them away from the coast.

The trade winds blow from east to west near the equator. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The trade winds blow from east to west near the equator. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

“Almost all of them just go out to sea. That’s why we never hear about them,” Kerry Emanuel, a hurricane professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told AP.

So, is climate change the culprit?

Simply put, the answer is yes. Scientists expected climate change to not only spike the occurrence of such hurricanes, but also make them more intense. A recent study, ‘Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change: Global Landfall Frequency Projections Derived from Knutson et al’, published in the journal American Meteorological Society, suggested that major hurricane landfalls in the eastern Pacific could become up to 30 per cent more frequent in case global temperatures soar by at least 2 degrees Celsius.

But why does climate change lead to more frequent and intense hurricanes? As mentioned before, it has to do with the surface temperatures of the oceans. The oceans are known to have absorbed 90 per cent of the additional heat generated by the greenhouse gas emissions in recent years. Due to this, global mean sea surface temperature has gone up by close to 0.9 degree Celsius since 1850 and around 0.6 degree Celsius over the last four decades.

Higher sea surface temperatures cause marine heat waves, an extreme weather event, which can also make storms like hurricanes and tropical cyclones more intense. Warmer temperatures escalate the rate of evaporation along with the transfer of heat from the oceans to the air. When storms travel across hot oceans, they gather more water vapour and heat. This results in stronger winds, heavier rainfall and more flooding when storms reach the land.

The situation has been worsened by the El Nino, developing for the first time in seven years, which has weakened the vertical wind shear in the eastern Pacific, allowing more hurricanes in the region. El Nino is a weather pattern that refers to an abnormal warming of surface waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. It is known to increase the likelihood of breaking temperature records and triggering more extreme heat in many parts of the world and in the ocean.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05