Explained Books | Conservation of species: Ecologists reflect

At The Feet Of Living Things: Twenty Five Years of Wildlife Research and Conservation in India covers a key period in modern India’s tryst with ecological sensitisation.

The book underlines that the diversity of life is both precious and beautiful. (Express file photo by Pavan Khengre)

The book underlines that the diversity of life is both precious and beautiful. (Express file photo by Pavan Khengre) First-hand accounts of ecologists are among the surest ways of comprehending one of the most difficult predicaments of our times: the environment-development conflict. They not only offer us insights into the complex demands placed on scientists but done sensitively, field stories also help us understand the unfolding of myriad human-nature interactions.

The field ecologist has played a key role in shining the light on the species we love and admire. They have also underlined why conservation should not be just about caring for a few charismatic species — the cats, elephants, whales, or Olive Ridleys. It’s also about knowing the value of creatures many of us might consider annoying, even dangerous.

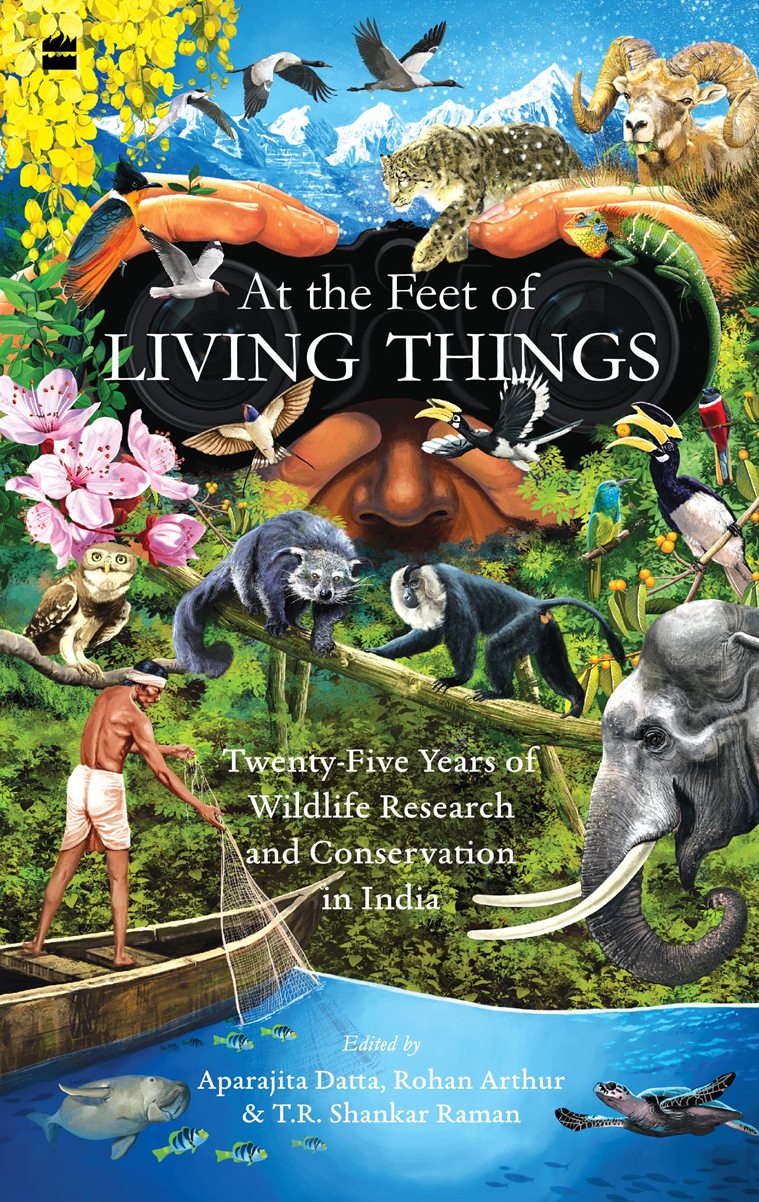

The cover of ‘At the Feet of Living Things’

The cover of ‘At the Feet of Living Things’

For millennia, communities have attempted to protect animals and plants for practical and spiritual reasons. However, for around two centuries or so, an anthropocentric view of the world created an ecological discord of sorts. Utilitarian ideas began to dominate attitudes towards nature, which often meant that even conservation had a strictly commercial purpose.

Modern environmental consciousness is a relatively recent phenomenon — perhaps about six decades old. In India, organisations such as the Bombay Natural History Society date back to the late 19th century and the endeavours of hunters-turned-conservationists played an important role in underlining the value of several species. But systematic efforts in mainstreaming ecology began much later and owed much to the works of pioneers like Salim Ali and M Krishnan.

At The Feet Of Living Things: Twenty Five Years of Wildlife Research and Conservation in India covers a key period in modern India’s tryst with ecological sensitisation. The articles in the volume, edited by Aparajita Datta, Rohan Arthur, and T R Shankar Raman are ostensibly about the on-field engagements of ecologists who in the mid-1990s explored the possibility of working outside the paradigm set by the government and government-run institutions and larger non-governmental bodies.

In 25 years, scientists from the Mysuru-headquartered Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) have made seminal contributions in understanding diverse locales — wetlands, high altitude forests, rainforests, scrublands, even arable plains. This is also the period in which the Indian economy was undergoing a shift — a process that continues — which led to new kinds of tensions in the human-nature relationship, and aggravated old ones.

That is why At The Feet Of Living Things is much more than a compilation of the experiences of field scientists from an institution that has engaged very creatively with several complex ecological questions of our times. Species as diverse as sea turtles, elephants, snow leopards, macaques, dugongs, mountain ungulates and hornbills find a place. The contributors engage with questions such as understanding the resilience of species in times when the human footprint is at its most prominent and terrains are contested.

There are chapters bearing the reflections and hopes of ecologists attempting to rekindle the bonds of children — like young Ammu, who in Swati Sidhu and Geeta Ramaswami’s chapter, ‘Citizens See The Season’s Change’ finds a teacher to share her curiosity and excitement — with nature.

The book underlines that the diversity of life is both precious and beautiful. As Aparajita Dutta writes in ‘Contested Terrain’: “The magic of forests is not only about spotting an animal — the glimpse of a startlingly coloured and rare root parasite is reward enough. There are moss-covered branches, snaking lianas, towering dipterocarp trees, the bright flashes of floors amidst the green, the tree ferns that look like relics from the past.”

Title | At the Feet of Living Things

Edited by: Aparajita Datta, Rohan Arthur, T R Shankar Raman

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers India

Pages: 400

Price: Rs 599

Explained Books summarises the main argument of an important work of non-fiction.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05