Desperate step in desperate times: Pakistan’s intent behind Pahalgam attack

The terror attack near Pahalgam comes at a time when Pakistan finds itself increasingly isolated on the international stage. It is an act of desperation, one which India must respond to with a cool head.

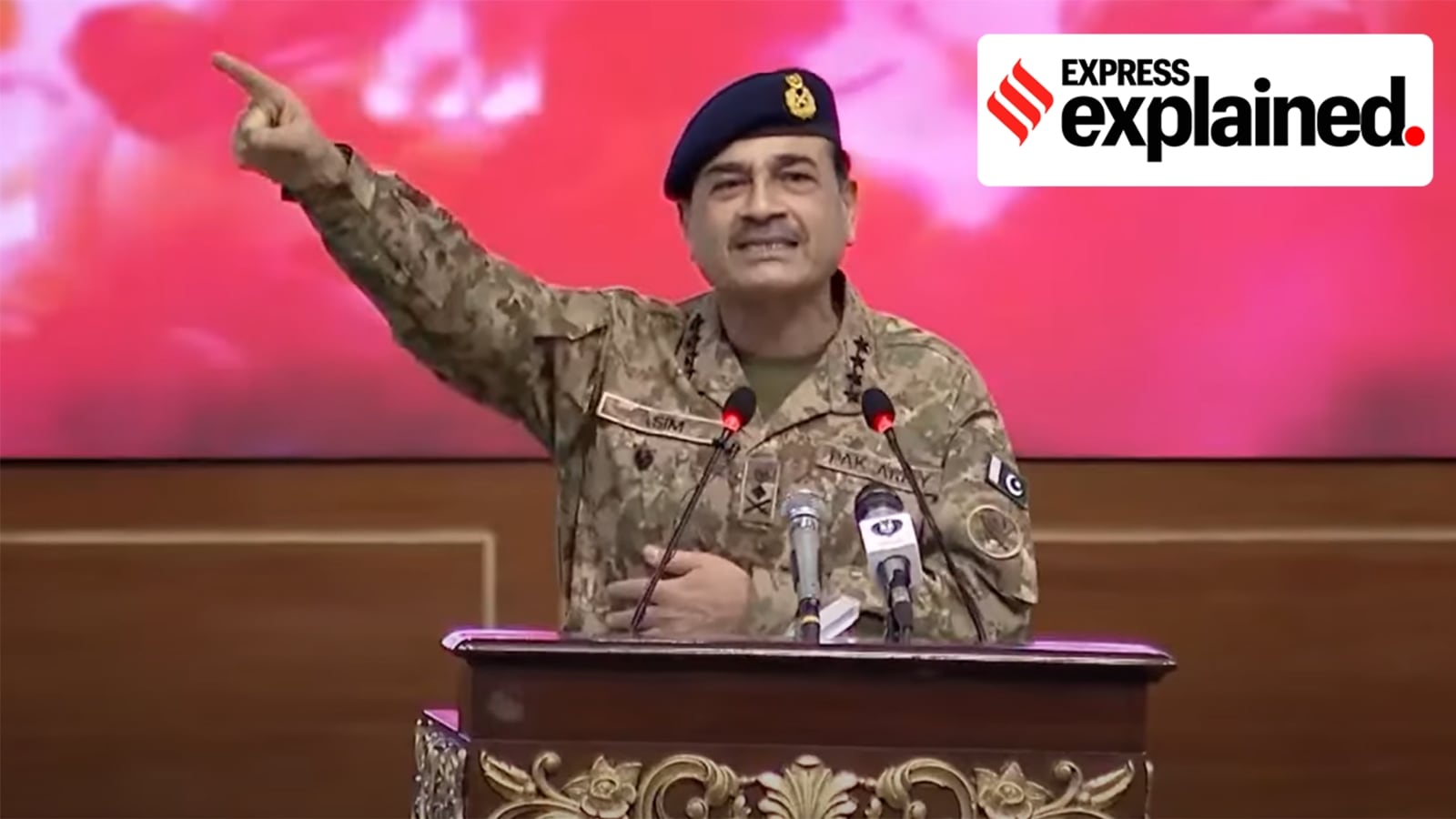

The terror attack in Pahalgam came a week after Pakistan Army Chief General Asim Munir went on an anti-India rant in Islamabad. (Image source: YouTube /ISPR Official)

The terror attack in Pahalgam came a week after Pakistan Army Chief General Asim Munir went on an anti-India rant in Islamabad. (Image source: YouTube /ISPR Official)A day after the Pahalgam terror attack, India on Wednesday announced a slew of diplomatic measures against Pakistan, including the suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty, expulsion of Pakistani personnel from India, and closure of the Attari border post.

Officially, Islamabad has denied any involvement. But initial investigations, and more importantly, the larger geopolitical context in which the attack has taken place, leave little doubt about Pakistan’s role.

Pakistan in dire straits

Pakistan today is a country in dire straits. Consider the following facts.

* For years, Pakistan was a key partner to the United States with regards to its objectives in Afghanistan — there could neither be war nor peace in Afghanistan without Islamabad’s support. With Washington pulling out of Kabul in 2021, the leverage that Pakistan enjoyed with the Americans is mostly gone.

Shutdown in Srinagar to protest the terror attack. (Express photo by Shuaib Masoodi)

Shutdown in Srinagar to protest the terror attack. (Express photo by Shuaib Masoodi)

And as it faces a crippling economic crisis, the US has not stepped in to bail Pakistan out, as it had repeatedly done in the past.

* The Gulf states too have refused to open up their coffers. There is fatigue among the Gulf states about having to repeatedly bail Pakistan out, and a sense that Islamabad has not given them much in return for doing so over the years.

* Even China has seemingly grown impatient with Pakistan. Beijing has poured in billions of dollars to develop infrastructure in Pakistan as a part of its flagship Belt and Road Initiative. But many of China’s projects in Pakistan remain stalled today.

Security personnel near the site of the Pahalgam terror attack.

Security personnel near the site of the Pahalgam terror attack.

Corruption and inefficiency aside, Pakistan’s inability to deliver on security promises has been responsible: in recent years, a number of Chinese engineers and project supervisors have been killed by Baloch terrorists. Although China remains Pakistan’s biggest patron, the two countries’ bilateral relationship is not what it used to be even in the very recent past.

* The Taliban regime in Kabul has not been the client state Pakistan had hoped it would be. Instead, it has turned rather hostile. Regions bordering Afghanistan have witnessed a spate of attacks on both civilians and military personnel.

Far from providing “strategic depth” to Pakistan against India, Taliban-ruled Afghanistan has become a serious security vulnerability.

* Pakistan’s border with Iran has not been much better. Just last week, eight Pakistani migrant workers were shot dead in Iran’s Sistan-Baluchestan province by a Baloch militant outfit. Last year, both countries targeted alleged “terrorist sanctuaries” on the other side of the border with missile strikes.

Such is the situation with its western neighbours today that some analysts would say Pakistan’s border with India is its most peaceful one at the moment.

All in all, Pakistan’s economy is in doldrums, its security situation is deteriorating, even as it feels more and more marginalised and isolated on the international stage.

‘India taking advantage’

In the eyes of Islamabad, India is taking advantage of Pakistan’s dire situation by isolating and marginalising it. New Delhi, in recent years, has acted as if Pakistan simply does not matter, that it is but a minor distraction for a country with ambitions of becoming a superpower.

This is perhaps most obvious with regard to India’s Kashmir policy, which treats Pakistan as a non-factor that is in no position to interfere with the largely successful attempts to bring stability and prosperity to the region. Contentious as it may be, the abrogation of Article 370 on August 5, 2019, which revoked Kashmir’s special status, was the strongest signal that India is looking to fully integrate the region with the rest of the country, regardless of Pakistan’s oft-stated position on the matter.

And in recent years, there has undoubtedly been a steady improvement in the economy and daily lives of Kashmiris, who ultimately benefit from stability in the region, regardless of their personal opinion of the ruling dispensation in Delhi. That a record number of tourists from all over India have been flocking to Kashmir is the ultimate bellwether of “normalcy”.

New Delhi has also successfully pushed the US to “de-hyphenate” its relations with India and Pakistan. That US Vice President J D Vance is currently on an official trip to India, with Pakistan being nowhere on his itinerary is proof of this fact.

Moreover, as India improves its ties with other Islamic countries in the Gulf, Pakistan has been little more than a silent spectator. It is noteworthy that the attack in Pahalgam took place while Prime Minister Narendra Modi was on an official visit to Saudi Arabia, a country which had been a steadfast ally to Pakistan during its wars with India, especially in 1971.

Pakistan’s desperate gambit

It is in this context that one can see a certain logic behind why Pakistan would take this rather desperate step. The terror attack in Pahalgam is essentially an attempt by Pakistan to assert that it is still a regional power which cannot simply be ignored or cast away as a non-factor, and the sense in India that “Pakistan does not matter” is misplaced.

This appears to make sense in the light of Pakistan Army Chief General Asim Munir’s statements last week, in which he repeatedly invoked the logic of the “two-nation theory”.

“Our religions are different, our customs are different, our traditions are different, our thoughts are different, our ambitions are different. That was the foundation of the two-nation theory that was laid there. We are two nations, we are not one nation,” General Munir said at the Overseas Pakistani Convention in Islamabad on April 15.

Beyond trying to shore up support for the beleaguered Pakistani establishment, this was essentially Munir saying that Pakistan is a country with its own identity, and thus has its own place in the world, which cannot be ignored and belittled.

In his statements, Munir also invoked Kashmir, which he referred to as the “jugular vein” of Pakistan. “Our stance is absolutely clear, it was our jugular vein, it will be our jugular vein, we will not forget it. We will not leave our Kashmiri brothers in their heroic struggle,” he said.

The attack in Pahalgam, can thus also be seen as an extension of Munir’s statements from last week: it is not only an attempt to undermine the progress made towards “normalcy”, but also a message to India that Kashmir cannot be stabilised without Pakistan as a stakeholder, and that India’s policy of integration is unacceptable to Islamabad.

Note that the precise timing of the attack, with PM Modi in Saudi Arabia and US Vice President Vance in India, suggests that it is as much a message to the rest of the world, as it is to India. Pakistan wants the world to know that it is still a critical player in the region, and has the capacity and capability to cause a serious security situation with potentially global ramifications, to prevent which there is no choice but to engage with Islamabad.

And even if the world reacts negatively to Pakistan — indeed countries from around the world have issued unequivocal condemnations of the terror attack — (Pakistan hopes) this will prompt greater engagement with it, if only as a bad actor. Amid its current international isolation, engagement of any kind would probably be received by Islamabad as a win.

India’s path forward

The first order of business for India is to analyse what went wrong. Were their lapses in the security arrangements? Were we too complacent? How can such attacks be prevented in the future so that tourists continue to travel to Kashmir without fear or trepidation?

An honest assessment is necessary to ensure that the progress Kashmir has been witnessing is not undone. And the Centre must leave aside its political differences with the National Conference, avoid a “blame-game”, and make the elected government an active stakeholder in this process.

Internationally, in the immediate term, India will certainly try to ensure that Pakistan remains isolated. If Pakistan believes that terror is a way to force other countries to engage with it, India will make sure that it is not.

With regards to retaliating against Pakistan, what is most important is that no action be taken based on emotions and public sentiment.

In the medium- to long-term, the attack should prompt India to rethink its assumption that Pakistan has been completely neutralised, and does not matter anymore. I have always believed that India has to engage with Pakistan. To completely isolate a neighbour with which it shares a 3,000 km border makes no sense. We have to continue talking to Pakistan, if only to know what it is thinking.

Moreover, New Delhi must appreciate that there is no one Pakistan. There is the Pakistani establishment, the elected government, as well as the people of Pakistan. Each constituency needs to be dealt with differently, and even if India has frayed relations with one of them, say the Army, it should continue to engage with the others.

At the end of the day, India’s long-term policy vis-à-vis Pakistan and Kashmir has to be centred around the people of Kashmir, and the region’s development and stabilisation. The attack must not interrupt the progress that is being made.

Shyam Saran served as India’s foreign secretary from 2004-06. Based on a conversation with Arjun Sengupta

- 0121 hours ago

- 0212 hours ago

- 0311 hours ago

- 0422 hours ago

- 051 day ago