Upon being taunted by police officers after revealing that the Rs 3 lakh in his possession is for the treatment of a little girl unrelated to him, Balachandran (Mammootty) reminds them that they shouldn’t disrespect a commoner who has approached the station seeking help. Smack! A blow lands across his face from one of the khaki-clad giants. In the subsequent moments in Kaiyoppu (2007), we get to see not only the soul of Balachandran but also why Mammootty is often regarded as the GOAT.

Unlike the many hypermasculine characters the Malayalam megastar has played over the years, Balachandran here is an altruist, even a simpleton at times. While his fear — mirroring that of every average person — at being in the police station is evident from the start, his body language upon receiving the slap also suggests this may be the first time he has received a physical blow. He loses balance and staggers, needing assistance from another cop to walk away. In his intense monologue, a minute later, Mammootty also showcases the intricacies of voice acting, demonstrating brilliantly how to play with the sensation of a ‘lump in the throat’, thus communicating different levels of sadness and desperation with finesse.

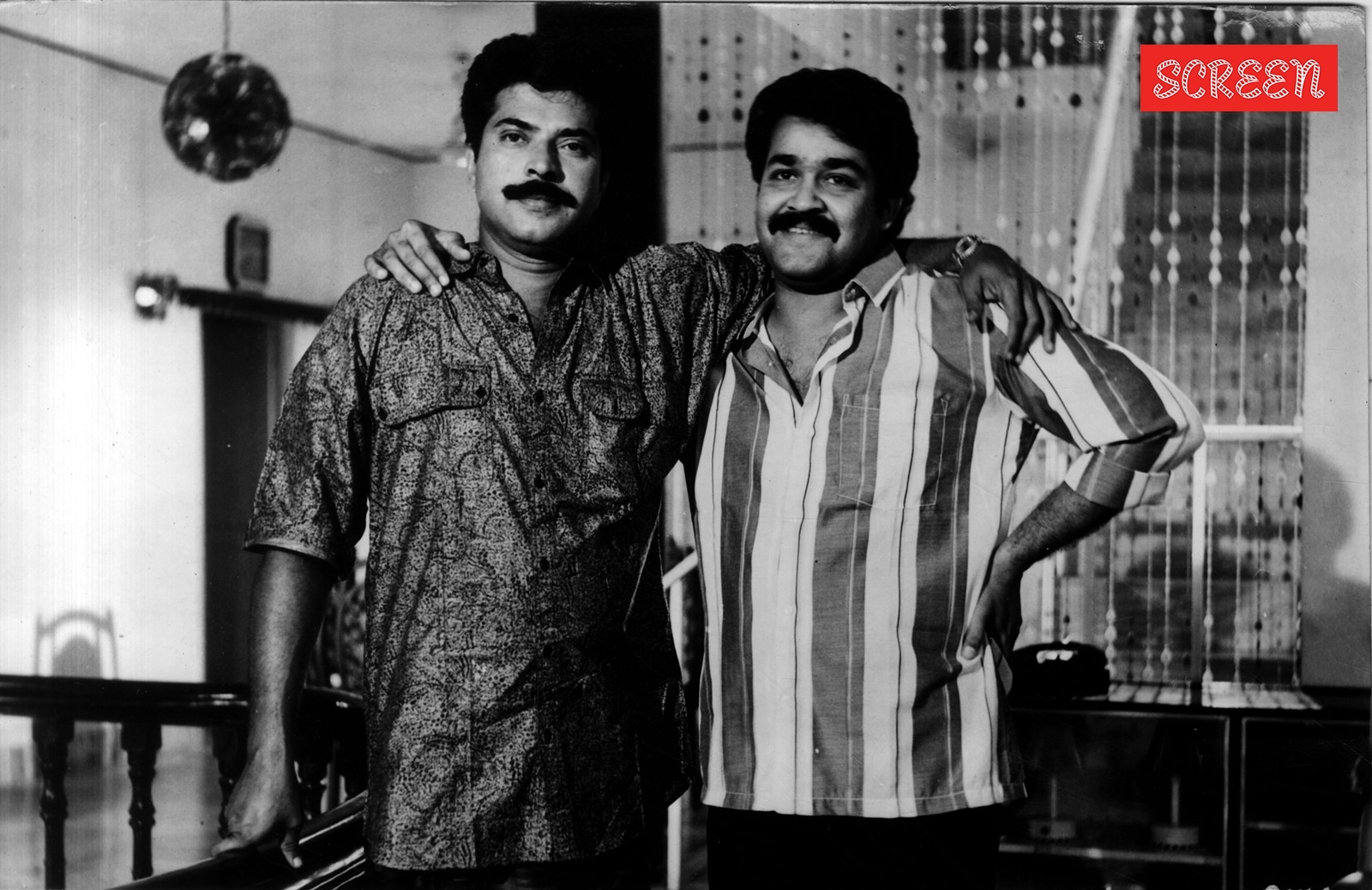

Legendary director Fazil, who has delivered several classics with both iconic thespians, once observed that, among the two, Mammootty is a better actor than Mohanlal. He reasoned that if Mammootty, despite his many shortcomings and limited skill set, managed to hold his own against Mohanlal, a jack of many trades, then the former is undoubtedly the better actor. It’s doubtful if anyone else has summarised their careers, talents, and the unofficial ‘clash of the titans’ going on between them for the past four decades in a more profound way.

Although Mammootty has long been hailed for his beauty, physique, and mannerisms, which have positioned him as the poster boy for Malayali masculinity, he does have many limitations as an actor. Several things that come naturally to Mohanlal, including comedy, dance, and action, don’t come as easily to Mammootty. His lack of physical flexibility, probably accentuated by his decades-old leg injury, is also a significant shortcoming for the actor.

Fazil observed that if Mammootty, despite his many shortcomings and limited skill set, managed to hold his own against Mohanlal, a jack of many trades, then the former is undoubtedly the better actor. (Express archive photo)

Fazil observed that if Mammootty, despite his many shortcomings and limited skill set, managed to hold his own against Mohanlal, a jack of many trades, then the former is undoubtedly the better actor. (Express archive photo)

Despite all these challenges, Mammootty has managed to stand toe to toe with Mohanlal for the past four decades, and that is the result of sheer hard work. “I am not a so-called born actor,” he has often stated. The brilliance of Mammootty is that he has only rarely made the audience feel this. “If I put in the effort and keep polishing my skills, I can shine brighter,” he once said during an interview. The 74-year-old thespian has done this without fail all these years, thus placing himself as one of the finest actors in Indian cinema, with three National Film Awards for Best Actor to his name — the second-most by any Indian actor, a record he shares with Kamal Haasan and Ajay Devgn.

Among the many skills that Mammootty has acquired over the years is his ability to effortlessly portray emotional scenes, conveying vulnerability and thus striking a chord with audiences. Much like the moment in Kaiyoppu, there are several instances where Mammootty delivered outstanding performances in tearful scenes, moving the audience. The beauty of his portrayals lies in the fact that he never goes out of character for dramatic effect to add an extra layer of sorrow, even though this might create a greater impact on the audience. Instead, he sticks to the right meter, expressing intense emotions with minimal expressions — sometimes through his quivering voice, twitches on his face, or simply by shedding or withholding a tear — completely based on the character’s nature and the emotional weight of the moment.

Mammootty in Sukrutham. (Express archive photo)

Mammootty in Sukrutham. (Express archive photo)

Take, for instance, his performance as Captain Thomas in cinema legend P Padmarajan’s Koodevide (1983). While Mammootty brilliantly maps his character’s emotional arc from start to finish, the restrained way he expresses his grief is particularly noteworthy. The only instance where he resorts to loud expressions is when the brake of his jeep has snapped and is about to ram Ravi (Rahman), whom he had been chasing with the vehicle. Immediately afterwards, Mammootty denies Thomas the luxury of shedding even a tear, thus emphasising the remorse the rigid Army officer feels towards himself. Although Padmarajan, being a meticulous director, would have given clear instructions to Mammootty, the actor’s ability to pull this off highlights his growth as an actor, in contrast to his initial caricatured performances.

Story continues below this ad

In the emotional moments in movies like Aa Raathri, Kanamarayathu, Ente Upasana, Adiyozhukkukal, Aalkkoottathil Thaniye, Thinkalaazhcha Nalla Divasam and Anubandham too, Mammootty manages to dive deep into the characters’ souls and extract their raw emotions with precision. He does not rely on his stock skills but treats each role as unique, striving to bring out its nuances. Even in tearful moments, Mammootty’s performances do not strike similarities; instead, he manages to reveal the essence of the character he’s portraying and the absoluteness of its predicament. By adding a layer of helplessness to the character’s emotions and a shade of innocence and contrition in his eyes, he hits the audience square in the chest, moving them to tears. From Nirakkoottu, Yathra and Poovinu Puthiya Poonthennal to Thaniyavarthanam, Oru Vadakkan Veeragatha and Mahayanam, his ability to portray emotional moments while staying true to the respective characters shines brightly.

On the other hand, in movies like Kottayam Kunjachan, where a bit of humour needs to be blended with the tears, or Aavanazhi and Inspector Balram, where the tears should be in constant conflict with the toxic masculinity of the roles, Mammootty magically brings forth a brilliant mix of everything. Even when characters have condemnable traits, Mammootty’s intense and anchored performances ensure that we too feel for these people when they are at their emotional lowest. Yet, the cries of Antony (Kauravar), Putturumees (Soorya Manasam), Achootty (Amaram), Devaraj (Thalapathi), Balachandran (Pappayude Swantham Appoos), Narasimha Mannadiyar (Dhruvam), Meledathu Raghvan Nair (Vatsalyam), Ravishankar (Sukrutham), Sanker Das (Azhakiya Ravanan), Madhavan Kutty (Hitler), Ravindranath (Arayannagalude Veedu), Arackal Madhavanunni (Valyettan), Major Bala (Kandukondain Kandukondain) or Amudhavan (Peranbu) do not appear the same as the actor knows well when to make his characters weep, whimper, sob, or wail.

With no dear ones by his side and an image as the tough guy, Sathyaprathapan in Chronic Bachelor (2003) has forgotten how to cry, and in such moments, Mammootty shows him immediately becoming awkward and pulling back into his cocoon, as he doesn’t know how to express his emotions. However, in Kaazhcha, we see the actor as Madhavan, a man who has no shame in showing his vulnerable side. His bond with Pawan (Yash Gawli) is, in fact, held together by tears; and as he pleads with the authorities for the boy’s custody towards the end of the film, Mammootty ensures that not a single audience member leaves with dry eyes.

Mammootty in Sagaram Sakshi. (Express archive photo)

Mammootty in Sagaram Sakshi. (Express archive photo)

In Thommanum Makkalum, Rappakal, and Rajamanikyam, on the other hand, he showcases three different cries from three distinct uneducated rural characters. Whether in Karutha Pakshikal, Palunku, or Ore Kadal, he ensures that the tears belong to the characters and not to him. As Fahadh Faasil once rightly pointed out, in Big B (2007), Mammootty demonstrates the art of crying without actually showing himself to cry through his conscious half-successful efforts to hide his tears.

Story continues below this ad

While he delivers a more expressive performance in Varsham, in tune with the film’s tone, he demonstrates in Unda that the depth of sorrow and humiliation can be conveyed through subtle shifts in voice modulation without resorting to extremes. Even as he portrays Luke Antony’s (Rorschach) tears turning him into a vengeance machine, Mammootty brilliantly differentiates between the emotional lows of James and Sundaram in Nanpakal Nerathu Mayakkam, based on their socio-economic backgrounds as well.

Watch SCREEN’s exclusive interview with Sudev Nair here:

One of the greatest, though indirect, ‘advantages’ Mammootty has always received is being widely regarded as the Valyettan (Elder Brother) of the Malayalam film industry. In a culture where men are raised to believe that “boys don’t cry”, seeing on screen a figure revered as the unofficial yet bona fide patriarch may have also been subconsciously influencing audiences, prompting them to empathise with Mammootty’s emotional expressions immediately. Regardless, just as the many shades of laughter he has portrayed have sparked discussions, his tears also deserve equal recognition as the megastar has delivered a unique cry for nearly every shade of character he has taken on.

Cinema cannot exist in a vacuum; it’s all about the discussions that follow. In the Cinema Anatomy column, we delve into the diverse layers and dimensions of films, aiming to uncover deeper meanings and foster continuous discourses.

Fazil observed that if Mammootty, despite his many shortcomings and limited skill set, managed to hold his own against Mohanlal, a jack of many trades, then the former is undoubtedly the better actor. (Express archive photo)

Fazil observed that if Mammootty, despite his many shortcomings and limited skill set, managed to hold his own against Mohanlal, a jack of many trades, then the former is undoubtedly the better actor. (Express archive photo) Mammootty in Sukrutham. (Express archive photo)

Mammootty in Sukrutham. (Express archive photo) Mammootty in Sagaram Sakshi. (Express archive photo)

Mammootty in Sagaram Sakshi. (Express archive photo)