The five-time Oscar nominee will likely earn his sixth nod for The Tragedy of Macbeth, continuing a streak of winless nominations that is slowly beginning to resemble the one that the great Roger Deakins began back in 1994. In a twist of irony that would make the Bard himself proud, Deakins was the Coens’ regular cinematographer before Delbonnel.

This is his fourth time working on a Coen brothers project—he also shot the duo’s Paris, je t’aime segment, went on to earn an Oscar nomination for Inside Llewyn Davis, and followed it up with dramatically diverse work on The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, an anthology in which each of the six shorts had a distinct visual palette. But Macbeth is the first time Joel Coen is directing by himself. And consequently, the first time that Delbonnel doesn’t have two sounding boards on a Coen set. Although he has, in the past, described them as ‘a single person, divided’.

Director Joel Coen (C) chats with Bruno Delbonnel (R) on the set of The Tragedy of Macbeth. (Photo: Apple TV+)

Director Joel Coen (C) chats with Bruno Delbonnel (R) on the set of The Tragedy of Macbeth. (Photo: Apple TV+)

There is something to be said about a man who got a start in television commercials—he told Deadline in a recent interview that he helped flog everything from cat food to washing detergent—and is now among the most in-demand cinematographers around. He said in the same interview that he turned down an offer to shoot Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch, which would have been remarkable because Anderson has almost exclusively worked with DP Robert Yeoman on; to the extent that his inimitable handcrafted visual style is as much Yeoman’s doing as it is his own. Delbonnel did, however, shoot Anderson’s brilliant H&M commercial a few years ago.

It wouldn’t have been the first time that a renowned filmmaker was willing to split from their regular cinematographer to work with him. Besides the Coens, who’d been working with Deakins since 1991, Delbonnel began a three-film run with Tim Burton in 2012, and shot two films for Joe Wright, when the filmmaker briefly separated from Seamus McGarvey after the disastrous Pan. Next up, Delbonnel will work on Alfonso Cuaron’s next, for which he is collaborating with the director’s partner-in-crime, the three-time Oscar-winner Emmanuel Lubezki.

But while each of those DPs can pride themselves on adapting to a director’s needs and changing things up–for instance, Lubezki has shot both Gravity and Children of Men–Delbonnel’s style is often more recognisable than most filmmakers’. For instance, both Darkest Hour and Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince looked more like Bruno Delbonnel movies than anything Wright or David Yates had ever done before.

Story continues below this ad

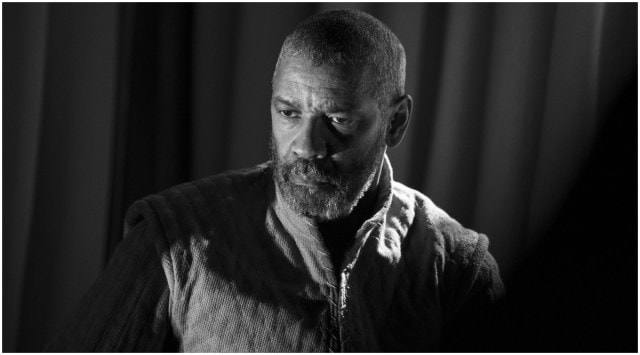

The Tragedy of Macbeth, shot entirely on Los Angeles sound stages in black-and-white Academy ratio, is unlike anything that either Coen or Delbonnel has ever attempted. It is a movie defined by its emptiness; the vacancy of its Brutalist hallways and the desolation of its deliberately artificial landscapes. Like Lars von Trier’s Dogville and Manderlay, it’s a movie that finds itself in the no man’s land between theatre and cinema.

And like those films, The Tragedy of Macbeth is almost as barren—not in a metaphorical sense, but quite literally. There are no windows on the walls of Macbeth’s castle; there is no furniture in his rooms; no carpets on his floors. A stark contrast, you’d agree, to the chaos raging inside his (scorpion-infested) mind.

In addition to the very pointed use of Shakespeare’s words, the film also presents a rather unique visual language. Combined, this creates a sort of dissonance in the viewer’s mind—an instant signal that they’re experiencing something abstract. In addition to the sense of confinement that the 4:3 aspect ratio communicates, the movie’s hat-tip to German Expressionism and film noir evokes a mood. You’re watching a story about a man gradually losing his mind, so it makes sense to pay homage to a genre whose protagonists were often torn apart by moral dilemmas.

Delbonnel captures the unraveling of Macbeth with high-contrast images combined with Coen’s rhythmic editing—jagged shadows in a courtyard can transition to almost painterly portraits that fill up the entire frame. And after a couple of predominantly grey acts, Delbonnel separates the film into a more distinct black and white, perhaps to mirror Macbeth’s descent into madness. He floods the cramped frame with greys once again in the film’s morally murky final act, as Washington comes in for one of his final close-ups, choosing to murmur one of the most important monologues ever written.

Story continues below this ad

It’s a showy performance, for sure. But so is the one that Delbonnel has put together behind the camera. It’ll be a shame if he isn’t recognised.

Post Credits Scene is a column in which we dissect new releases every week, with particular focus on context, craft, and characters. Because there’s always something to fixate about once the dust has settled.

Director Joel Coen (C) chats with Bruno Delbonnel (R) on the set of The Tragedy of Macbeth. (Photo: Apple TV+)

Director Joel Coen (C) chats with Bruno Delbonnel (R) on the set of The Tragedy of Macbeth. (Photo: Apple TV+)