Click here to join Express Pune WhatsApp channel and get a curated list of our stories

Hidden Stories: A hunger strike that revived a Pune river, a litigation that tried to give it new life

A flood in 2010 served as a wake-up call, leading two Pune women to put up a fight for Ramnadi, a river that many discredited as a drain.

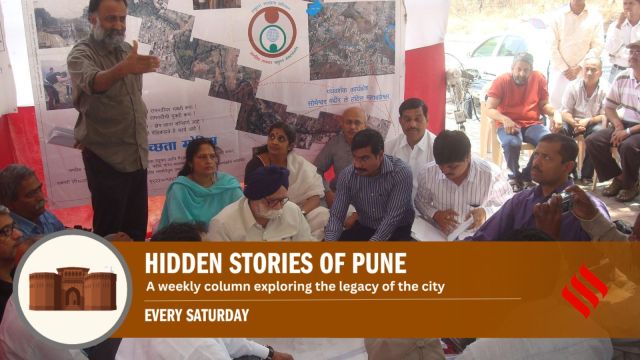

On April 24, 2011, the duo (Indu Gupta and Dr Pragati Kaushal) sat on a hunger strike with Jal Biradari members at the gate of Ramnagar Colony. It was the first time that anybody in the city was on strike for a river. Mayor Mohan Singh Rajpal (in frame) arrived to hear them.

On April 24, 2011, the duo (Indu Gupta and Dr Pragati Kaushal) sat on a hunger strike with Jal Biradari members at the gate of Ramnagar Colony. It was the first time that anybody in the city was on strike for a river. Mayor Mohan Singh Rajpal (in frame) arrived to hear them.On September 29, 2010, Indu Gupta and her family were fast asleep at their home in Saikamal Residency in Pune’s Bavdhan when the floods arrived. Six feet of water swept into their house, which is located at a low level and close to the Ramnadi.

Sitting on the grounds of the house, whose high wall overlooks the river, Gupta scrolls through her phone’s gallery to show photos of ruined computers and other belongings from then. Snakes, worms and fish lay in the muck deposited by the water. “Our lives were saved only because we were on the first floor. Everything on the lower floor was destroyed. It was a wake-up call for us,” she says.

Among those who visited Gupta after the flood were members of Jal Biradari, a grassroots social movement that “mobilises and empowers masses to help them solve water-related problems through public participation”. What these experts had to tell Gupta was worrying – “Such floods would occur annually unless we take action,” she says. The cause of the floods—which had taken several lives in Bavdhan and Pashan – was said to be unauthorised construction on the river and the blocking of the waterway.

Another Saikamal resident, Dr Pragati Kaushal.Pragati Kaushal (left) and Indu Gupta is the director of an interior design firm in Pune.(right)

Another Saikamal resident, Dr Pragati Kaushal.Pragati Kaushal (left) and Indu Gupta is the director of an interior design firm in Pune.(right)

Gupta, the director of an interior design firm, had always been socially active. “I am a fighter, it is my nature,” she says. But, this was the first time that she found herself taking up cudgels against the administration. Among the people who stood by her was another Saikamal resident, Dr Pragati Kaushal. “We are poles apart by nature but we work together very well,” says Kaushal.

They began by visiting the civic authorities. “The Ramnadi has two parents – the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) on one side and the collector on the other. When we went to one, we were directed to the other. So, we started going to both offices. Almost every day, Pragati and I were at their offices,” says Gupta.

From September 2010 to April 2011, there was no action from the civic bodies. Running from one office to another was, clearly, not yielding results. On April 24, 2011, the duo sat on a hunger strike with Jal Biradari members at the gate of Ramnagar Colony. It was the first time that anybody in the city was on strike for a river. The fast attracted more than 30,000 people, including children. “That’s how we brought government officials to our tent rather than go to their rooms,” says Gupta.

Gupta’s hobby is taking photographs, and her balcony, which overlooks the river and brings a wide variety of birds, is her favourite watchtower.

Gupta’s hobby is taking photographs, and her balcony, which overlooks the river and brings a wide variety of birds, is her favourite watchtower.

Then mayor Mohan Singh Rajpal arrived to hear them. The result was that the Ramnadi was dredged and cleaned and its width was increased so that it began to look like a river. “In the next rainy season, it was flowing beautifully,” says Gupta.

A new fight

Gupta’s hobby is taking photographs, and her balcony, which overlooks the river and brings a wide variety of birds, is her favourite watchtower. It is from here that, in 2013, Gupta first noticed that a building site was coming up on the other side of the river “and they were dumping debris on the Ramnadi”. “Again, our fight started,” she says.

This time, Gupta and Kaushal would go all the way to the National Green Tribunal (NGT). Their partner in this endeavour included well-known environmentalist Sarang Yadwadkar.

The Indu Gupta & Ors. Vs. Goel Ganga & Ors case, filed at the Western Zone Bench, Pune, has become a landmark in environment action in Pune as it pitched members of the civil society against a major builder. “Tareekh pe tareekh pe tareekh padti jaati thi,” says Gupta, referring to the repeated adjournments and hearing dates.

She says the Ramnadi used to be referred to as a naala or drain in many official documents. “In the case of a river, there can be no construction in the red and blue floodlines. In the case of a naala, there is no such restriction so unscrupulous builders used to tweak the terms to their advantage. There was zabardast (tremendous) pressure on us to withdraw the case. Builders would offer us flats and money,” says Kaushal.

It was her husband, who works with satellite images, who found photographs of the river. “We had all the documents as evidence. Added to this were my photographs taken from the balcony to show the river and encroachments,” says Gupta.

As the case dragged on, Gupta realised that her health would not permit her to pursue it actively. When the NGT shifted to Delhi, it became impossible for the duo to carry on the struggle. They had invested their own money – several lakh rupees were spent on colour photocopies of documents alone to give to courts.

“Adhura reh gaya hai kaam (our work lies incomplete),” says Kaushal.

“What we won was that this river was officially declared at NGT as Ramnadi, a river, and not a naala or drain. Our success is also in drawing attention to the river,” says Gupta.

Click here to join Express Pune WhatsApp channel and get a curated list of our stories