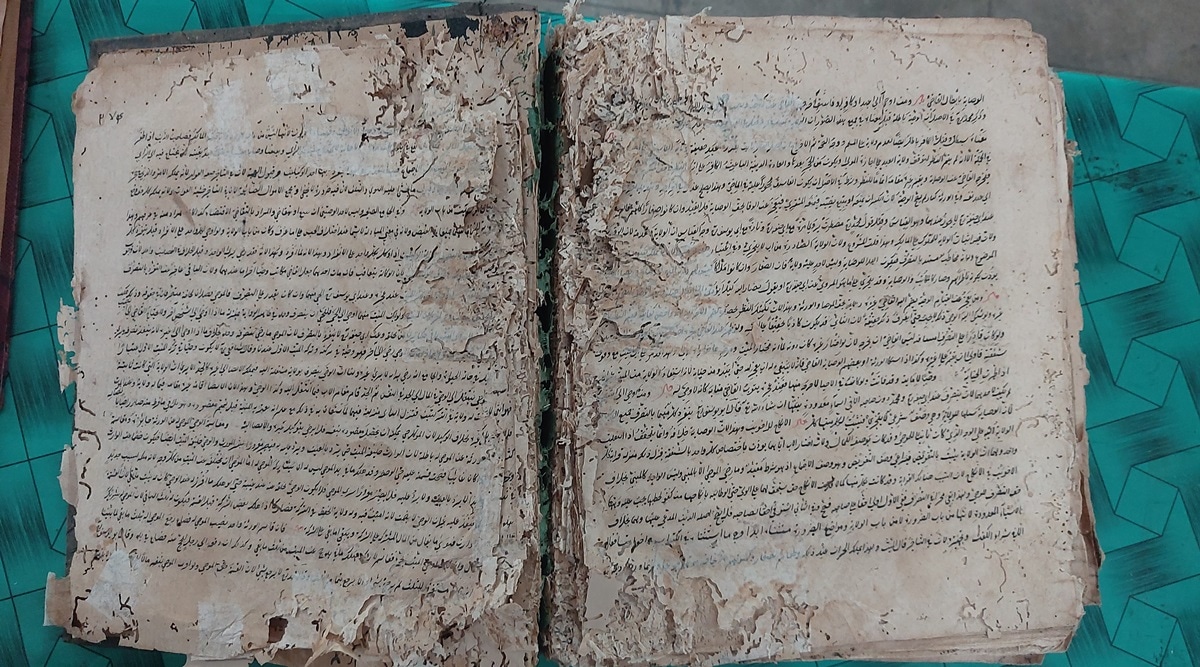

The oldest available document at the Telangana State Archives and Research Institute (TSARI) in Hyderabad is a farman – royal edict – bearing the calligraphic monogram and seal of Feroz Shah Bahmani, dated 14 May 1406, regarding the grant of land in Qasba Kalyanabad (Basavakalyan in Karnataka) as inaam (reward) to a Maulana Muhammad Qazi. This hand-written document in the classical Persian language, perhaps the oldest available Persian document in the country, is among the 33 million historical documents and manuscripts that are currently undergoing a process of restoration, preservation and cataloguing for posterity.

The TSARI is home to a rich repository of about 44 million archival materials, over 80 per cent of which is in the classical Persian and Urdu languages – two official languages of the erstwhile Hyderabad Deccan. Starting from the life and times of Bahmani rulers, who broke away from the Delhi Sultanate to form Deccan’s first Muslim dynasty, to its subsequent breakaway Deccan Sultanates of Ahmednagar, Bidar, Bijapur, Berar and Golconda, the TSARI has perhaps the largest collection of the Mughal-era documents under emperors Shah Jahan and Aurangazeb. Available in greater detail are documents from the Asaf Jahi-era as the Nizams ruled over the Deccan for the next 224 years until India’s independence from the British.

Copy of the oldest Firman dating back to May 1406 — sourced from TSARI

Copy of the oldest Firman dating back to May 1406 — sourced from TSARI

Apart from 45,000-odd farmans, the records in TSARI’s possession include official treaties, land records, revenue and finance department records, survey documents and maps, orders of the courts, etc. “What we have is an invaluable treasure trove that needs to be preserved for future generations. Buried in documents are insights into the social atmosphere, cultural attitude, economic and financial situations, and the secular fabric of the Deccan. To know the reality of the times, one needs to study these manuscripts,” said Dr Zareena Parveen, director of TSARI.

Preserving Indo-Iran heritage

In September 2022, the TSARI signed a memorandum of understanding with the Noor International Microfilm Centre (NIMC), a Delhi-based organisation supported by the Iran government, to give these historical documents a fresh lease of life. The cost, estimated at around Rs 4 crore, is being borne by the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran. “The two countries share a common cultural history. Two Iranian Presidents, Mohammed Khatami in 2003 and Hassan Rouhani in 2012, have visited our state archives. They were extremely happy to see our archival collections,” she recalled.

A catalogue with English summaries of Farmans originally in Persian. (Rahul V Pisharody)

A catalogue with English summaries of Farmans originally in Persian. (Rahul V Pisharody)

Persian was the official language in the region from the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in 1206 up until 1884 when the sixth Nizam of Hyderabad Mir Mahboob Ali Khan replaced it with Urdu as the official language.

Ali Akbar Noorimand, regional director, explaining the digitisation process of archival material.(Rahul V Pisharody)

Ali Akbar Noorimand, regional director, explaining the digitisation process of archival material.(Rahul V Pisharody)

Adding that securing these documents was an important aspect in the preservation of the common heritage of the two countries, NIMC’s regional director Ali Akbar Niroomand said more than 80,000 documents have been repaired, in addition to another 670 bound manuscripts that have been repaired and digitised in the last six months. “These documents can now survive at least 200 years. Had the work not started right now, we would have lost much of them forever in another five years,” he said. To its credit, NIMC uses a unique technique in the repair and conservation of documents that allows the present work to be easily undone to adopt a better technique that may evolve in the future.

From evaluating the extent of damage to digitisation

At a corner hall on the first floor of TSARI, a team of conservation and digitisation experts work from 10 am to 6 pm, six days a week. Their job starts with taking a closer look at the documents to evaluate the extent of the damage. If in good shape, they proceed with digitisation. If the damage is minimal, an additional layer of paper is stuck to borders to strengthen them and forwarded for digitisation. The real work starts when the papers are brittle and fragile or eaten away in patches or corners by termites.

Story continues below this ad

Facsimile or replica copies of Firmans from 1899 to 1902 bound in the form of a book for easy reference (Rahul V Pisharody)

Facsimile or replica copies of Firmans from 1899 to 1902 bound in the form of a book for easy reference (Rahul V Pisharody)

According to Niroomand, NIMC’s treatment process is unique and distinct since it uses herbal glue, handmade paper, chiffon cloth, and special insect-and-termite-resistant boxes – all developed by its founder-director Mahdi Khaja Piri. Once the book is opened up after removing the binding, each page is soaked in a herbal solution that acts as an adhesive as well as a cleanser. In a simple yet effective manner, the wet page is placed in a chiffon cloth on either side, pressed on a machine, dried and bound again.

“But before removing the binding, we look at the type of paper and ink used. We add serial numbers to pages after matching ‘capture word’ in the manuscript to ensure continuity,” said Md Rizwan, who oversees the repairs process. A capture word that is mentioned at the bottom of the page indicates the first word on the next page. “That was how manuscripts followed pagination. This way, we know if any page has gone missing already.”. This method of restoration, which he called ‘the pasting method’, takes four to five days for a bound batch of manuscripts.

An archival paper (right) preserved a few years ago using an old method in comparison to the one that underwent preservation using NIMC’s technique now (on the left). (Rahul V Pisharody)

An archival paper (right) preserved a few years ago using an old method in comparison to the one that underwent preservation using NIMC’s technique now (on the left). (Rahul V Pisharody)

Many of the documents here were preserved using earlier techniques that used acetone, plastic, butter paper, etc., at different points in time. While it gave documents a life of eight to 10 years, the paper used to swell under humidity, turn brittle and powder up in the long run. “The advantage of our way of restoration is that we can remove the paper from the chiffon cloth by just washing it with water. Unlike the earlier methods of restoration, we can undo and adopt a better technique if that happens in the future,” said Habib Ashraf who leads the digitisation efforts.

After repair and preservation of documents, they are placed inside insect-and-termite-resistant boxes for longevity. (Rahul V Pisharody)

After repair and preservation of documents, they are placed inside insect-and-termite-resistant boxes for longevity. (Rahul V Pisharody)

TSARI traces origins to record office of 1724

Story continues below this ad

According to the TSARI director, the Mughals used the best quality of paper and indelible ink and systematically recorded every event on paper. “We have 5,000 documents from Shah Jahan’s time and 1.5 lakh documents from Aurangazeb’s time. The military, administration and revenue records show graphic detail of the Deccan under the Mughals. The Nizams who broke away from the Mughals to declare independence followed the same system of maintaining records and administrative system,” said Dr Parveen, adding that the present-day TSARI has its origins in the Dafter-e-Diwani mal-o-mulki established by the Nizam in 1724. All records were issued in classical Persian script and pertains to 14 administrative offices across six provinces.

The team of conservation and digitisation experts of NIMC at TSARI (Rahul V Pisharody)

The team of conservation and digitisation experts of NIMC at TSARI (Rahul V Pisharody)

The Dafter-e-Diwani mal-o-mulki became a regular record office in 1896 and was upgraded to the status of a Directorate in 1923. After Indian independence, the office became Andhra Pradesh State Archives in 1962 and was upgraded to a research institute in 1992. After the creation of Telangana state in 2014, all documents that belonged to Andhra were shifted out. “These documents and manuscripts were deteriorating with every passing day. Upon completion of the project, a short reference to the catalogue material will be made available on our website and researchers from the world over can visit us with specific research requirements. All original records will remain in the safe custody as facsimile copies will be available for reference purposes,” she added.

NIMC uses high-resolution cameras mounted upside down from a frame to capture documents placed on a platform inside well-illuminated cabinets. Each of the cameras is attached to a laptop to store the captured image. After collation, the data is secured in a hard disk. “The original document is safely taken back by the staff at TSARI to the section from where it came. This way, there is no scope for losing or misplacing any document,” Niroomand added.

A partially damaged archival page before its repair (Rahul V Pisharody)

A partially damaged archival page before its repair (Rahul V Pisharody)

Using the digitised material, they also make facsimile copies or replica copies for reference purposes so that the original need not be taken out every time and can be placed in safe custody. “These copies are as good as the original and use our special handmade paper that gives longevity,” he added.

Copy of the oldest Firman dating back to May 1406 — sourced from TSARI

Copy of the oldest Firman dating back to May 1406 — sourced from TSARI A catalogue with English summaries of Farmans originally in Persian. (Rahul V Pisharody)

A catalogue with English summaries of Farmans originally in Persian. (Rahul V Pisharody) Ali Akbar Noorimand, regional director, explaining the digitisation process of archival material.(Rahul V Pisharody)

Ali Akbar Noorimand, regional director, explaining the digitisation process of archival material.(Rahul V Pisharody) Facsimile or replica copies of Firmans from 1899 to 1902 bound in the form of a book for easy reference (Rahul V Pisharody)

Facsimile or replica copies of Firmans from 1899 to 1902 bound in the form of a book for easy reference (Rahul V Pisharody) An archival paper (right) preserved a few years ago using an old method in comparison to the one that underwent preservation using NIMC’s technique now (on the left). (Rahul V Pisharody)

An archival paper (right) preserved a few years ago using an old method in comparison to the one that underwent preservation using NIMC’s technique now (on the left). (Rahul V Pisharody) After repair and preservation of documents, they are placed inside insect-and-termite-resistant boxes for longevity. (Rahul V Pisharody)

After repair and preservation of documents, they are placed inside insect-and-termite-resistant boxes for longevity. (Rahul V Pisharody) The team of conservation and digitisation experts of NIMC at TSARI (Rahul V Pisharody)

The team of conservation and digitisation experts of NIMC at TSARI (Rahul V Pisharody) A partially damaged archival page before its repair (Rahul V Pisharody)

A partially damaged archival page before its repair (Rahul V Pisharody)