Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

Unsung Heroes: B K Singh, a hero of the Karnataka forest department who once faced Veerappan’s bullets

In 1990, B K Singh was part of a team of officials that entered the forests to locate sandalwood stock near Silvekal when Veerappan and his gang opened fire at them, injuring two policemen, forcing them to abandon the operation.

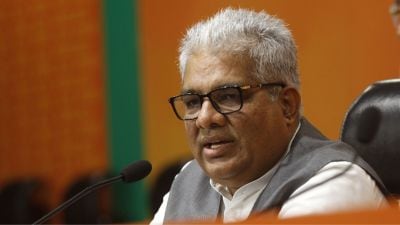

B K Singh.

B K Singh.Sifting through official documents at his house in BTM Layout, Bengaluru, B K Singh, the former principal chief conservator of forests (head of forest force), is preparing to write a book on conservation and reminiscing about his distinguished career. Looking back nine years after his retirement, Singh says when he got his first posting in 1978 in the Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka, he had no idea that years down the line, he would encounter the dreaded smuggler Veerappan, who would end up playing a big part in Singh’s career.

Not only did Singh face Veerappan and survive an exchange of bullets in the jungles of Karnataka, as the head of the Karnataka forest department in the latter half of his career, he refused to buckle under the pressure of politicians who were openly vouching for encroachers.

“This gang (Veerappan’s gang) had been in the trade of elephant tusks since 1985. Elephants were mainly poached in Hosur, Dharmapuri, Erode and Satyamangalam divisions of Tamil Nadu and in Kollegal, Chamarajanagar, Bandipur, Hunsur and Madikeri divisions of Karnataka. The modus operandi used to be that the gang would camp near a water hole in the forests for as many as three to four days, wait for elephant herds to come, spot tuskers, move close and fire a shot in the forehead or between the two front legs, resulting in instantaneous death. The remaining elephants would run away and the tusks were extracted from the dead tusker,” Singh explained.

Singh recalled an incident on July 31, 1989 when a team of forest officials opened fire on bamboo smugglers who had the patronage of Veerappan. Four days later, Singh said, in the presence of forest staff, the brigand killed the forest guard, Mohanaiah, and escaped.

Singh recalled an incident on July 31, 1989 when a team of forest officials opened fire on bamboo smugglers who had the patronage of Veerappan. Four days later, Singh said, in the presence of forest staff, the brigand killed the forest guard, Mohanaiah, and escaped.

A former Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer, P Srinivas, got Veerappan arrested in 1986 during the SAARC summit but he escaped due to the negligence of policemen, Singh said. “It was during this period that Veerappan started targeting forest officials as well. In 1991, Arjuna (Veerappan’s brother), who was lodged in a jail in Mysuru, was released on bail. Through Arjuna, Srinivas sent messages to the smuggler for surrender. On November 9, Srinivas got to know from Arjuna that Veerappan would surrender before him at Namtali, a place in the forests 6 km from Gopinatham. He walked into the trap and was shot dead and beheaded. We lost a brave officer. Srinivas worked to provide water supply to the village, established healthcare facilities where Veerappan’s sister worked as nurse and also renovated a temple,” Singh added.

In 1988, Singh was posted as deputy conservator of forests, Kollegal. “I could not go on for reconnaissance in the forest at will since Veerappan had confined his movement in the forests in Kollegal and in the adjoining forests of Dharmapuri and Erode forest divisions of Tamil Nadu,” Singh recalled. “After the killing of a few forest department personnel and informants, forest staff stopped entering interior forests and they also stopped getting any information from villagers. With great difficulty, I succeeded in getting the police to intervene. Earlier, the police did not intervene since the matters were related to wildlife protection but when the murders took place, I had asked them to intervene. Then later forest personnel and policemen took up aggressive patrolling in the jungle,” he said.

Singh recalled an incident on July 31, 1989 when a team of forest officials opened fire on bamboo smugglers who had the patronage of Veerappan. Four days later, Singh said, in the presence of forest staff, the brigand killed the forest guard, Mohanaiah, and escaped. “We visited the parents of the forest guard and delivered his body to them,” he said.

Less than a year later, Singh, himself, ended up ‘meeting’ Veerappan during a failed operation to seize sandalwood. “I received specific information regarding storage of sandalwood stock near Silvekal. Immediately, I called for police help and on January 6, 1990, a team of 50-odd policemen led by superintendent of police of Mysore district, Bipin Gopal Krishna, accompanied me and some other forest staff to the spot to locate this stock with the help of the said informant. Members of the Veerappan gang guarding the stock opened fire at us, two policemen were injured and the operation was abandoned,” he said. The hidden stock of sandalwood was eventually recovered in February, with the help of the Tamil Nadu and Karnataka police and forest officers from both the states, Singh added.

Singh says he once turned down the suggestion of the forest department to form a human chain around the location of Veerappan’s hideout in a bid to nab him.

Finally, after Veerappan was killed in 2004, the Karnataka forest department sent a recommendation to the state government, where everyone who contributed towards the success of the operation was to be rewarded on par with their counterparts in Tamil Nadu. “This list included 250 men and officers. The file was shunted between the finance secretariat and forest secretariat. I had also requested former forest minister Ramanath Rai to get the file cleared, when I was PCCF (HoFF) Karnataka. The proposal was reworked and the list was brought down to six. Quickly, a government order was issued rewarding these six persons. Some of the remaining persons from the list of 250 have tried to take legal recourse and challenged this order in the court of law…they have not succeeded,” he pointed out.

Later, during his career, Singh says he had a face-off with political leaders, one of whom became the chief minister of Karnataka. “Shivamogga, even today, has massive encroachment of forest areas. One of the MLAs who later rose to become the CM had a confrontation with me when he supported the encroachers. He went to the higher-ups to get me transferred. While that did not happen, even today, the officers face massive opposition while evicting encroachers. Local farmers organisations during protest enter the forest and cut trees and in every new season, they encroach the forest lands to cultivate. I have faced immense pressure from political parties,” said Singh, who currently teaches forest economics at Dharwad Forest Academ