William Dalrymple’s next: How Ancient India changed the world

The Golden Road, out in September, will narrate India’s position as a ‘crucial economic and civilisational hub' in ancient Eurasia

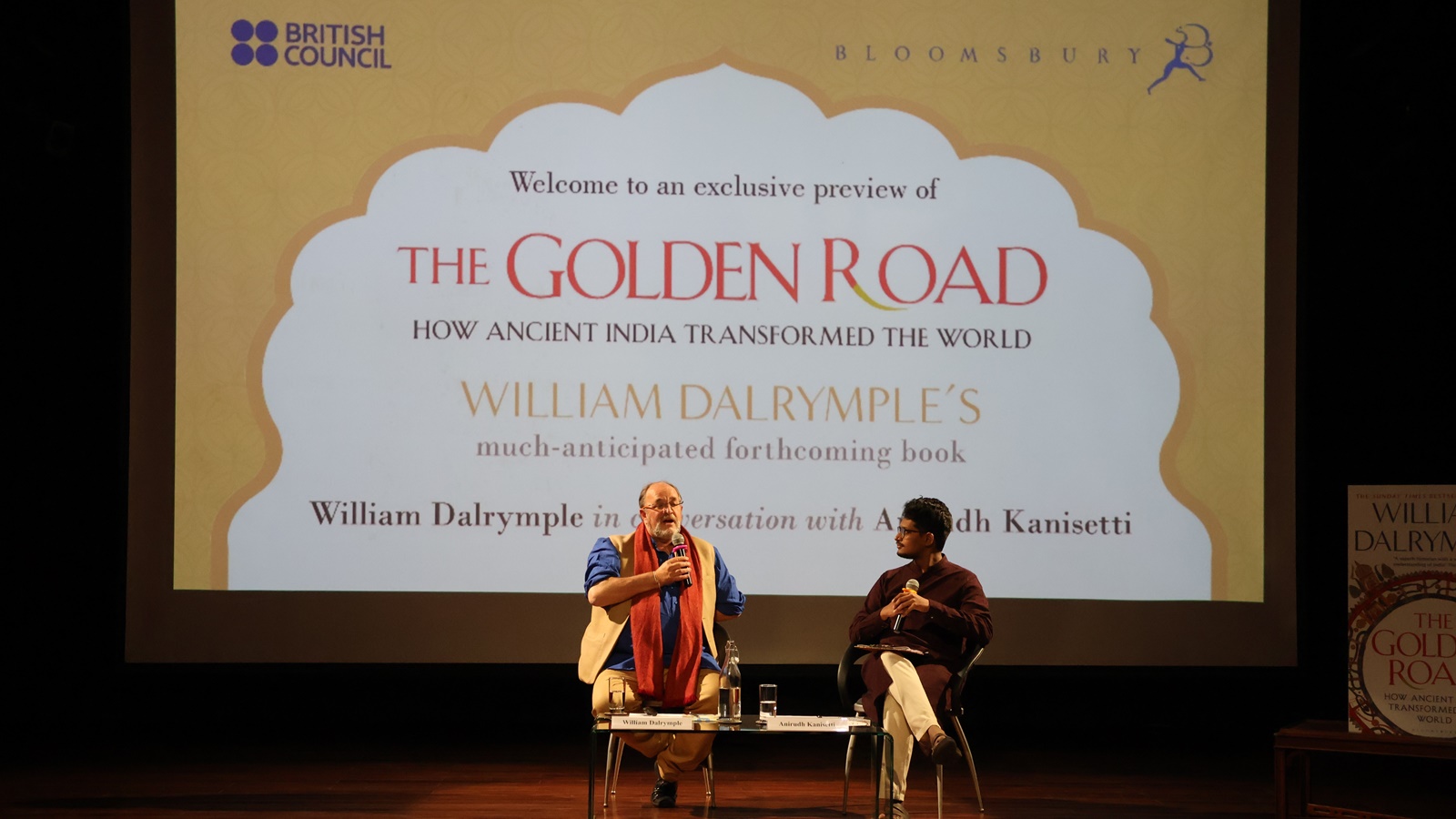

William Dalrymple talks about his new book (Source: Bloomsbury)

William Dalrymple talks about his new book (Source: Bloomsbury)Irritated by the Silk Road always being studied as one of the earliest international trade routes – completely sidestepping India – and inspired by a visit to Cambodia’s Angkor Wat – the largest Hindu temple in the world – historian William Dalrymple started compiling material on a story of Indian sociocultural influence. He named it the ‘Indosphere’, a zone of influence that preceded the Silk Road and allowed subcontinental arts, cultures and sciences to spread outward, from “Afghanistan in the west to Japan in the east”.

“We should recover the centrality of India (in trade till the 13th century) but not in a jingoistic way,” he said at a preview of his next book, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World (Rs 999, Bloomsbury) last month. He added that India became the “fulcrum of international trade and commerce” not because of military conquest but the “sheer sophistication and attractiveness” of its ideas.

He was in conversation with historian Anirudh Kanisetti about India’s western and eastern coasts interacting with the world, how Buddhism and the number ‘zero’ originated from the country to travel the globe, and why this cultural influence slowed after the 13th century.

The story began with how Ancient Rome’s gold helped develop south India, with massive coin hoards still being discovered in present-day Kerala. A document called Muziris Papyrus details the items bought by a Greek shipper from a Cochin merchant, spanning spices, elephant tusks, and nard (a holy perfume). “A third of the Roman imperial budget,” emphasised Dalrymple, “came from the customs’ take on the Red Sea. The value of one shipment was enough to make you one of the richest men in the Roman empire.”

When Rome fell in the fifth century, India, “used to gold coming in”, shifted trade focus from the west to the east coast. That’s when Indian ideas started appearing in Cambodia, Sanskrit started becoming a language of diplomacy, and Buddhism traveled from north to south India.

“We take for granted that a single Indian culture was accepted (in this period), but most people (in south India) were not Hindu or Buddhist, instead burying their dead under megaliths and hero stones. Buddhism was an alien religion but a prestige was associated with it,” said Kanisetti.

“This was a far more globalised world than we today imagine,” said Dalrymple, referring to how Roman legionaries retired in south Indian kingdoms, Greek women protected palaces and harems, and Buddhist monasteries got donations from foreign merchants. High-speed monsoon winds allowed people and ideas to travel fast over sea, enforcing settlements and interactions with new cultures while you waited for the rains again.

Meanwhile, Buddhism had travelled from India to China in the first and second centuries, initially perceived as a religion of foreigners. A holocaust of Chinese culture in the third century allowed Buddhism to seep in during the reign of Empress Wu, the only female emperor in Chinese history. She converted her entire court to the religion and denounced the Confucian and Taoist establishment.

William Dalrymple’s new book (Source: Amazon)

William Dalrymple’s new book (Source: Amazon)

Indian mathematics had also begun its slow journey west. A delegation of Ujjain’s mathematicians and astronomers met the Barmakids, viziers in-charge of the Arab world. Eventually, the Barmakids fell from grace, but many Sanskrit texts had already been placed in present-day Iraq. Persian mathematician Khwarizmi arrived a generation later and simplified Aryabhatta’s highly compressed mathematical texts for the Arab world. Eventually, Fibonnaci, from Italy, came to stay in Algeria, learnt Arabic numbers, and brought them back to the Italian court. “Ironically, it’s the facility with mathematics this gives to the Europeans… which ultimately boomerangs back (to India with the East India Company),” said Dalrymple.

Such diverse cultural and scientific ideas stopped transmitting after the 13th century for a few reasons. The Turkish invasions began, later leading to the Mughal Empire; Mongol invasions cut off old trade routes; and the Silk Road was opened up, connecting the Mediterranean and South China Sea.

“What gave Indian mathematicians their edge was that India was already this cosmopolitan place where ideas were coming in from Persia, Babylon, and the Greek world,” said Dalrymple. “Indian mathematicians were not coming up with these ideas out of nothing. They were stitching together existing ideas, bringing them a stage further. That ability to learn from other cultures in a non-chauvinistic way is the genius step.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05