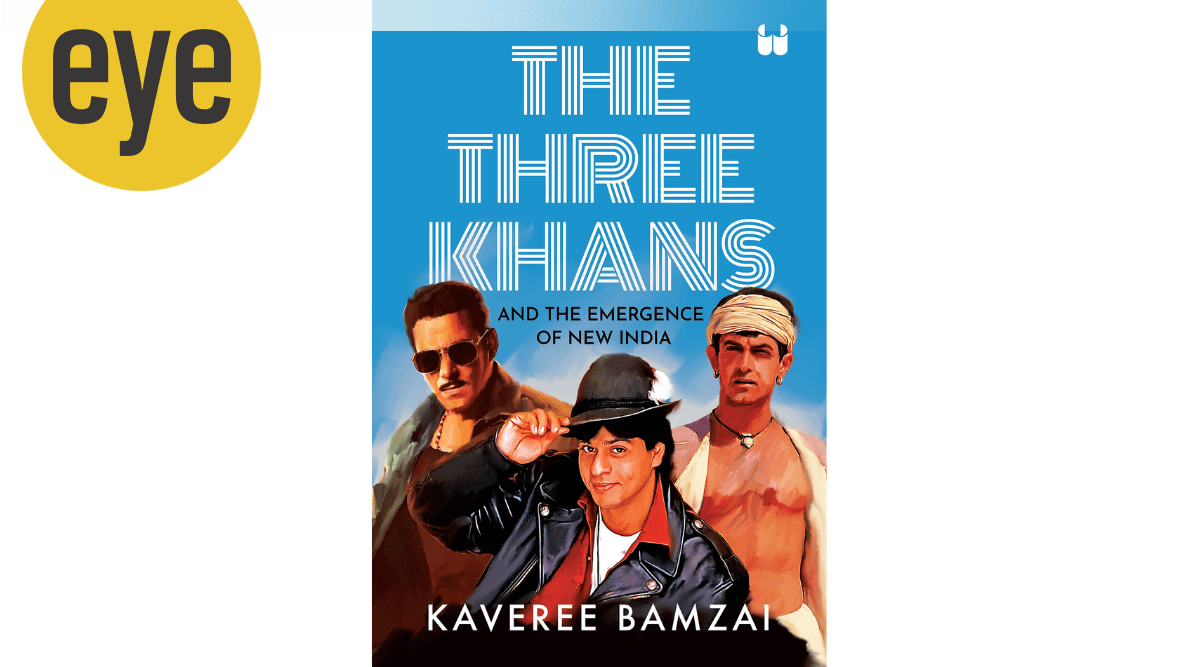

Why Kaveree Bamzai’s new book, The Three Khans of Bollywood, fails to land

From mapping history to anecdotes, the book presents how the superstars improvised and built on the language of popular cinema

The hounding of Bollywood is now a spectacle we consume. But what makes it a worthy target to be taken down? What language does it speak so well to the “people” – that entity crucial to politicians and the market – that the current ideological re-engineering of India by Hindu right-wing forces must take it on? Senior journalist Kaveree Bamzai’s book on the three Khans and three superstars of Hindi cinema – Shah Rukh, Salman and Aamir — whose careers have played out in the last three tumultuous decades of Indian life could have contained answers to some of these questions. It doesn’t. That’s not the only count on which The Three Khans disappoints. The bigger let-down is that it remains a bits-and-pieces collage of the three actors’ lives, when it could have been a defining narrative of their criss-crossing journeys.

A part of the problem lies in the subtitle’s ambition. Bamzai’s attempt to map the Khans’ careers against a larger political climate leads her into a clumsy decade-by-decade structure that lumps everything together – revealing gossip, irrelevant news. Joining the dots between cinema and history leads to simplistic juxtapositions. Long, perplexing passages list dates and events in a way that remain unconnected from the creative choices of the actors – like strangers on a train, but definitely not interested in doing any Chhaiya Chhaiya. It drains the narrative of all the energies it could have tapped if it had focussed, instead, on three immersive portraits of the two Bombay boys and their Delhi challenger. It is, as if, the collective idea of the Khans and “their zeitgeist” killed all curiosity about their specific histories and trajectories. Or, how they improvised and built on the language of popular cinema. While film magazines as well as the work of several film writers and scholars are cited, the author’s own point of view is a curious silence in the book. There is a strange refusal to be drawn into interpretation of her subject, or engage with other interpretations, which leaves the reader adrift in the material.