From Delhi to Dorset: Reading Jane Austen across continents

250 years of Jane Austen: Chaotic households, prescriptive gender roles, women striving to exercise moral agency, and even courtship rituals staged through song, dance, and spectacle make the author an enduring presence in the Indian subcontinent.

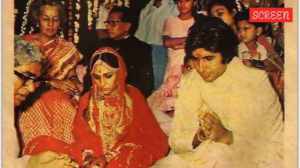

The marriage market that Austen satirises, with its expectation of dowries, inheritance, and class mobility, is strikingly familiar to us in the Indian subcontinent. (Source: Wikimedia Commons and Unsplash/Dexter Fernandes)

The marriage market that Austen satirises, with its expectation of dowries, inheritance, and class mobility, is strikingly familiar to us in the Indian subcontinent. (Source: Wikimedia Commons and Unsplash/Dexter Fernandes) (Written by Aditi Upmanyu)

This year marks 250 years of Jane Austen, and while she has always been a beloved author, the enthusiasm feels especially renewed now: new adaptations on OTT platforms, attractive reprinted editions in bookshops, and Austen-themed festivals are bourgeoning across the UK. The celebratory fervour takes me back to my first encounter as an undergraduate at Miranda House, reading Pride and Prejudice in an airy, red-bricked classroom. If Paradise Lost and Sons and Lovers made morning lectures challenging, Austen’s novel sparked unusually lively discussions even in the early hours.

Our orange-spined Penguin editions were dense with pencilled notes, specific scenes finding a corollary in our own social worlds. Amusement over Mrs Bennet’s frantic hunt for wealthy suitors for her daughters would give way to more serious conversations about morality, marriage, and how our own futures might be mediated by similar expectations. In the liberating space of a women’s college, where solidarities were forged from shared experiences, we felt a kinship with Austen’s heroines. Separated from her by time and geography, reading her fiction nonetheless felt like deciphering our own cultural script.

Unsurprisingly, Jane Austen translates seamlessly into South Asian storytelling traditions, in Bollywood films such as Bride and Prejudice and Aisha, or in novelistic retellings such as Soniah Kamal’s Unmarriageable. Chaotic households, prescriptive gender roles, women striving to exercise moral agency, and even courtship rituals staged through song, dance, and spectacle make her an enduring presence in the subcontinent.

An evolving relationship with Austen

Our orange-spined Penguin editions were dense with pencilled notes, specific scenes finding a corollary in our own social worlds. (Unsplash:Zoe/Dominika Walczak)

Our orange-spined Penguin editions were dense with pencilled notes, specific scenes finding a corollary in our own social worlds. (Unsplash:Zoe/Dominika Walczak)

Now, as a researcher studying 18th-century women writers, I continue to reflect on my evolving relationship with the author. I moved to the UK in my late 20s, at a time when many friends back home were getting married. In an admittedly clichéd way, I felt my story mirrored Austen’s. Away from the camaraderie of Delhi’s reading circles, I began seeking her in new ways, not only in her novels but in the literary landscapes of England.

The first of these encounters came by chance, when I visited friends in Dorset over Christmas and learned of the fleeting, but memorable time Austen spent here. Drawn to the stunning, windswept coast of Lyme Regis, she found inspiration for Persuasion, her only novel with a heroine considered “mature” at twenty seven. Moving from the hot, humid air of Delhi to the frosty December breeze of Dorset, my understanding of Austen deepened, from cataloguing cultural parallels in her work to contemplating the quiet complexities of her later fiction.

Over the summer, I explored wisteria-laden Bath, a quintessential eighteenth-century spa town that draws innumerable tourists to its historic Roman Baths. In her novels, Bath’s Pump Rooms and Royal Crescent are sites for romantic rendezvous for the young and leisurely repose for the wealthy class. While Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey famously exclaims, “Oh! Who can ever be tired of Bath?” Austen herself found the town’s endless balls, amorous intrigues, and social theatre exhausting. In her fiction, Bath is a dazzling but morally regulated stage of performance and propriety. Today, fans in Regency costumes flock to its cobbled streets, tea parties, Austen-themed tours, and, more recently, Bridgerton’s filming locations. Bath sets the stage for a lively society but not necessarily for the literary introspection Austen desired.

Walking through the town, with its theatres, assembly rooms, and inventively constructed streets, I am reminded that Austen’s world is shaped and sustained by the empire. In Mansfield Park, the Bertrams’ wealth rests on Sir Thomas’s plantation in Antigua, and Fanny Price, treated as an inferior dependent in their home, is a reminder that English women could be subjected to the same power structures that perpetuate colonial oppression. Though Austen did not write about India directly, her world was tied to it; in Northanger Abbey, Henry Tilney boasts of his knowledge of “true Indian” muslin. The novel ties his patriarchal authority to the colonial exploitation that drove English consumerism. This entanglement of gender, colonisation and economics resonates in South Asia, where the imperial legacies still linger.

The marriage market that Austen satirises, with its expectation of dowries, inheritance, and class mobility, is strikingly familiar to us in the Indian subcontinent. Austen adaptations to present-day Asian contexts are not only about romantic parallels, but such social and political affinities. Our anxieties about marrying “well” are partly a colonial inheritance, when English economic and cultural norms took root here.

Austen’s homes and lasting legacy

In Hampshire in southern England, her presence is carefully preserved and curated. Her house-turned-museum in the idyllic village of Chawton feels intimate, sunlit and immediately welcoming. (Unsplash/Gordie Jackson)

In Hampshire in southern England, her presence is carefully preserved and curated. Her house-turned-museum in the idyllic village of Chawton feels intimate, sunlit and immediately welcoming. (Unsplash/Gordie Jackson)

To truly understand Austen and her life, even beyond the intricacies of her fiction, I turn to the private spaces that shaped her imagination. In Hampshire in southern England, her presence is carefully preserved and curated. Her house-turned-museum in the idyllic village of Chawton feels intimate, sunlit and immediately welcoming. Her letters and diary entries, writing desk and other everyday belongings are on display, vividly bringing Austen to life. Here she appears not only as a writer but as someone deeply attached to her home, a loving aunt to her nieces and nephews, and a lifelong companion to her sister Cassandra, who was a prolific artist in her own right. Cassandra’s sketches, alongside the ephemera of the Austen household, together offer an evocative portrait of a witty, perceptive, and passionate woman who chose a life of creative flourish over marriage and courtship.

Nearby, at her brother’s grand estate, Chawton House, a library holds vast archives of books and manuscripts that offer insight into the lives of now-obscured women writers who preceded and inspired Austen. Her sister and her mother, also named Cassandra, are buried close by in St Nicholas Church.

While Chawton feels lively and solitary at once, the neighbouring town of Winchester memorialises a more mournful past. A short bus ride away, Austen spent her last days here. Inside Winchester Cathedral, better known for its male-dominated Anglo-Saxon history, her modest burial makes no mention of her as a writer, though a commemorative plaque was later installed. Behind the cathedral, in a quiet lane dotted with quaint bookshops, stands the unassuming house where she passed away after a fatal illness at merely forty-one.

Oxford’s Austen connection

At the age of seven, she came with Cassandra and a cousin to study under Mrs. Ann Cawley, widow of a Brasenose principal, the very college I would later join. (janeaustenproject.org)

At the age of seven, she came with Cassandra and a cousin to study under Mrs. Ann Cawley, widow of a Brasenose principal, the very college I would later join. (janeaustenproject.org)

Living and studying at Oxford, I was surprised to learn about Austen’s connections to the university town. At the age of seven, she came with Cassandra and a cousin to study under Mrs. Ann Cawley, widow of a Brasenose principal, the very college I would later join. Her father and brother were Oxford-educated, and so are her fictional men. As a South Asian woman at the hallowed university, my presence here echoes, even if fleetingly, Austen’s sense of being an outsider in a scholarly world that, in her time, belonged entirely to men.

That Austen endures in public memory is why I return to her places whenever I can, retracing old paths in Chawton, Winchester and Bath in different seasons, and seeking new ones in her birthplace, Steventon and Derbyshire. Each visit reveals facets of her life previously unknown to me. In exploring her life and work from Delhi to Dorset, I have learned that her creative legacy shapes my life as a woman and sustains my love for English literature. To read her is to travel across global landscapes, histories and cultures, and to journey into one’s own inner world.

(The writer is a DPhil candidate in English at the University of Oxford.)

As I See It is a space for bookish reflection, part personal essay and part love letter to the written word.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05