A new English translation of Shrikant Verma’s Magadh is a tribute to its timelessness and to the growth of its translator

The translator’s note tells that Rahul Soni has been living with Magadh for 15 years. The present volume is a revised version of the translation he had published a decade ago

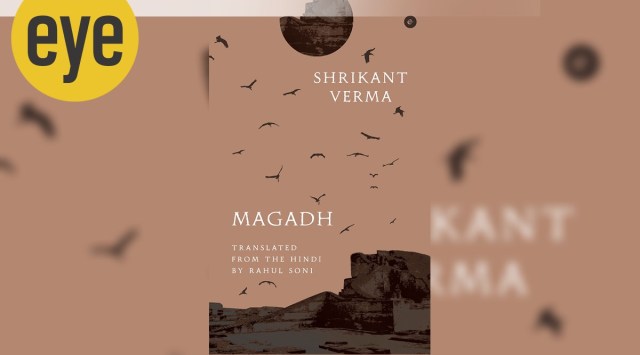

Magadh, Shrikant Verma, Translated by Rahul Soni, Eka (Westland Books), Rs 599. (Source: Amazon.in)

Magadh, Shrikant Verma, Translated by Rahul Soni, Eka (Westland Books), Rs 599. (Source: Amazon.in)The January 30, 1984 diary of Shrikant Verma has a frenzied precision and prophecy. “These poems were buried deep inside for years. They are now emerging — inadvertently. I am writing daily, discovering a new idiom. The primary concern/subject of these poems is — death, destruction, moral degradation. I will prepare a poetry collection in two months.”

Thus emerged Magadh (1984), perhaps among the greatest, most significant poetry books by a poet-politician in the 20th century. A Rajya Sabha MP and Congress’s general secretary, Verma was close to Indira Gandhi since the late 1960s. He was deeply entrenched in the country’s power corridor and enjoyed its trappings. In an April 1984 letter to the writer-friend Krishna Baldev Vaid, Verma assured him of the Indian International Centre’s membership, and underlined how he had similarly pitched in for Nirmal Verma recently. In their mid-50s then, both Nirmal and Vaid were giants in themselves, but they couldn’t perhaps match up to their influential friend who was an integral part of a regime they had opposed during the Emergency.

As if only someone deeply immersed in sins could have so accurately diagnosed both its causes and symptoms, as well as carried a desire to resurrection, Magadh marks the redemption of a poet.

Magadh is a blistering indictment of decadent regimes, a melancholic tale of lofty ambitions and the futility of seductions. The sitting Congress MP dedicated the book to Nirmal Verma, a staunch opponent of the Emergency. You don’t need another testimony about the autonomy of the republic of literature.

But a reader need not be acquainted with the above political context. A great work may offer a commentary to its immediate milieu, but it always transcends the temporality. Verma drew the titles of poems from Indian history — Avanti, Hastinapur, Ashoka, Kalinga, Rohitashva. But one need not be even aware of the legends these nouns carry. Each of these can be read as short compositions in melancholia, or one can read the entire volume as a long epic.

These poems are about people who lose their identities in the cruel vortex their ambitions throw them in. The verses invade you with such an intimate mirror that they instantly leave you searching for a consoling corner. “Kya isse kuch fark padega/agar main kahun/main Magadh ka nahin/Avanti ka hun?/Avashya padega/ tum Avanti ke maan liye jaoge/Magadh ko bhulna padega…Tab tum duhraoge/Main Avanti ka nahin/Magadh ka hun/aur koi nahin manega …Magadh ke/ maane nahin jaoge/Avanti men/pehchane nahin jaoge (Will it make a difference/if I say/I’m not from Magadh/I’m from Avanti?/Of course it will/you’ll be taken to belong to Avanti/you’ll have to forget Magadh…Then you’ll say/I’m not from Avanti/I’m from Magadh/and no one will believe you… No one will believe you are/ from Magadh/No one will recognize you/ in Avanti.)”

At the centre of these poems is an unnamed narrator — kaal, a profound term that denotes time, death, but which also signifies a restless desire for immortality in Magadh.

The narrator may also remind you of the traveller in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities who narrates the bewildering tales of the many cities he had visited to the bedazzled emperor, each tale leaving the king with more questions than ever.

The narrator first tells the travellers going to Ujjaini that “every road goes to Ujjaini/and that/no road goes to Ujjaini…Then/where should those going to Ujjaini go? They should go to Ujjaini/ and say/ This is not Ujjaini/ because we/ did not arrive here on the roads/ that go to Ujjaini/or on the roads/that don’t go to Ujjaini”. As he contradicts his own prophecies, he challenges your vision and perception.

But Magadh would be a lesser work had it been a mere lament. Because the decay is inevitable, irrespective of the path you chose, it makes the fall and the consequent tragedy all the more alluring.

The aesthetically produced volume is superbly translated into English by the editor-translator Rahul Soni, who has rendered several important books from Hindi into English, including a selection of Ashok Vajpeyi’s poems, A Name for Every Leaf (2016), and Geetanjali Shree’s The Roof Beneath Their Feet (2013).

The translator’s note tells that Soni has been living with Magadh for 15 years. The present volume is a revised version of the translation he had published a decade ago. Read both the versions to discern the growth of the translator.

Consider this: The 2013 translation of Kosambi ke badle/keval/Kosambi/mil sakti hai goes “The only alternative/ to Kosambi/is Kosambi.” The latest translation goes: In return for/ Kosambi/you can get/only Kosambi.

Several years ago, when I travelled across central India reporting on the Naxal insurgency, I read a paper, Magadh Ki Mrityu Kamna (The Death Wish of Magadh) in a seminar held on Shrikant Verma in his home state of Chhattisgarh. Just as it is human nature to often yearn for an epic love, I proposed, writers spend their lives in search of an epic work. Both the desires can simultaneously consume and destroy you for their sheer impossibility. Magadh not only realises its ambition, but also leaves you with an even more unsettling question: It’s immaterial to have arrived home/the question is where do you go now?

Ashutosh Bhardwaj is a journalist and a writer

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05