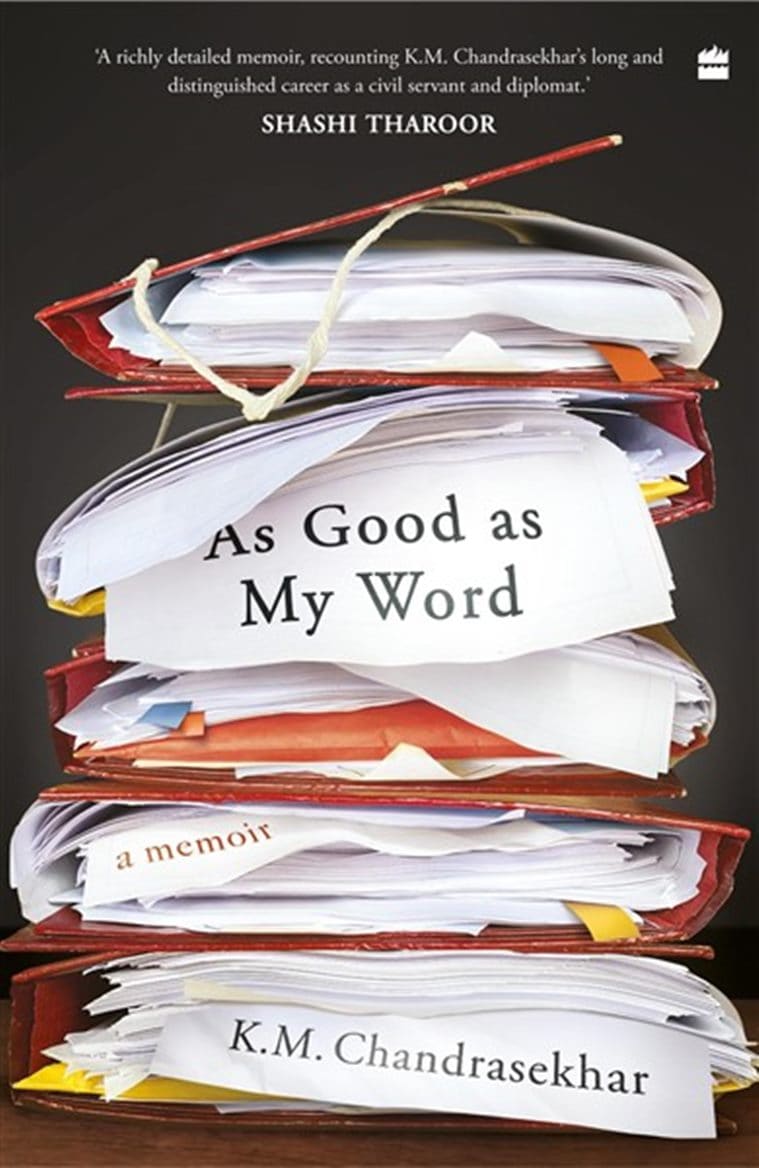

Former bureaucrat KM Chandrasekhar’s memoir offers a ringside view of the workings of India’s corridors of power

The wide sweep of the book gives sufficient food for reflection on the role of our constitutional, statutory, and regulatory authorities

Taj Mahal Palace hotel at Colaba in Mumbai lit up as part of preparations of G-20 summit (Express photo by Pradip Das)

Taj Mahal Palace hotel at Colaba in Mumbai lit up as part of preparations of G-20 summit (Express photo by Pradip Das) As Good as My Word by KM Chandrasekhar, who was the Cabinet Secretary from 2007-2011, starts as an autobiography with graphic details of his childhood, schooling and college education, set within the confines of a modest but disciplined Malayali home. The next part delves into his joining the IAS and the early years in his home state Kerala. Both segments, however, pale into insignificance compared to the latter part of the book which deals with a largely unknown but hugely important world of international trade. This is followed by a throwback into a series of tumultuous political events, including recent ones — and their cascading effect on public polity.

The stories about the author’s successes and failures in the Kerala years (every obstacle turning into a triumph) are no different from how most IAS officers describe their postings in the state governments. References to Messrs Amitabh Kant and Ajit Doval — also of the Kerala cadre (who continue to be big names in the Narendra Modi government) — describe how the two officers had distinguished themselves early on in their service. The author also has several good words for Kerala politicians and does not seem to have faced the sort of Machiavellian manipulation or skulduggery which pepper most books written by IAS officers. Stories about the leadership, knowledge, and tenacity of ministers such as Murasoli Maran, Arun Jaitley and Arun Shourie are exhaustive and inspiring. The only personal chapter, which belongs to the Delhi part of his career, describes the sudden death of his daughter — a simple but heartrending account which changes the tenor of the book.

The book scores high on unravelling how developed countries suppress the needs of developing countries during trade negotiations. Since the G20 is on, the book is topical because it rewinds back to 2003 when the group took shape. The US and the EU had blended a perfect formula for imposing a self-selected list of tariff reductions. How India created a counter-narrative by teaming up first with Brazil, then China and how the ambassadors of South Africa, Egypt and Thailand came on board, at the G20, portrays how India flashed the mirror at the rich man’s club.

The 1991 economic reforms have been compared by KMC to the first and second Industrial Revolutions in Great Britain and Europe, to the age of Henry Ford in the US and the effervescence of the Chinese economy under Deng Xiaoping. Fulsome praise has been accorded to then Finance Minister Manmohan Singh “who never demanded shortcuts in public service and believed in process with utmost importance given to integrity, openness and decision making through consensus building.”

As Good as My Word: A Memoir by KM Chandrasekhar; HarperCollins; 312 pages; Rs 599 (Source: harpercollins.co.in)

As Good as My Word: A Memoir by KM Chandrasekhar; HarperCollins; 312 pages; Rs 599 (Source: harpercollins.co.in)

The real meat of the book is, however, in the last portion, where the author deals with a series of events when he was cabinet secretary, followed by an account of those that took place subsequently. Those descriptions expose how an inarticulate government could be tormented by an eye-ball hungry media, which received ample fodder from the usually faceless Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG), how the organisation and its head had no compunction in providing exaggerated reports which were devoured by the media and the courts even before they had been debated in Parliament. The author is critical of this action, making no allowances for service camaraderie. He rings alarm bells about how officers can be and have been humiliated and even imprisoned because of preposterous conclusions drawn in the 2G and the coal scams by divulging how unprocessed reports led to the denigration of institutions, systems and crushed initiative.

Since Chandrasekhar was the revenue secretary before becoming cabinet secretary, that part of the book exposes how efforts to reform the income-tax law have been made constantly but never acted upon; how the misuse of the Enforcement Directorate and the Department of Revenue Intelligence can, if they fall into wrong hands, become instruments of oppression. The introduction of GST and demonetisation have been written about in some detail, including how businesses and the industry came to a grinding halt.

In describing dictatorships across world history, what starts as a digression serves the author’s objective of bringing in India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who according to the author, “ensured that India did not go the authoritarian way because of his conviction that consensus building was the essence of democracy.”

For an outsider hungry to know what goes on inside the corridors of power, the book provides telling accounts of how truncated intelligence reporting has resulted in avoidable dichotomies between the key arms of the government. The descriptions of the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai are a case in point and show how high-level coordination does (or does not) take place, and how the Centre and states interact during emergency situations. The book exposes weakness in decision-making at the highest level (during the attacks), with different key organisations reporting to the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Cabinet Secretary, the National Security Advisor, and the Department of Revenue — a situation that begs correction.

Elsewhere, references to the Ambani brothers, their influence in price fixation of gas and how a minister lost his job for demurring over a decision, have been referred to in passing, providing the reader with enough nuggets on “how successive governments enriched a company and an individual, at the cost of the nation.”

The 2010 Commonwealth Games along with the distasteful shenanigans of Suresh Kalmadi and his run-ins with the then Minister for Sports, Sunil Dutt, is a commentary on how, at times, powerful people assume extra-constitutional authority and by their sheer bluster command obeisance. Chandrasekhar has hearty praise for Sheila Dikshit, the then Delhi chief minister, who went beyond the call of duty to see that every link in the chain was connected, despite a slew of obstacles.

The author’s criticism of irresponsible public-sector banks, the lack of focus and ill-considered decisions in the economic front, especially on the winding up of the Planning Commission and its substitution by the Niti Aayog “without adequate preparation” is one of the first candid assessments made by a former civil servant.

In discussing the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, Chandrasekhar advocates clarity in policy-making and having an understanding that performance, trust, and the ability to communicate carry more weight than engendering hate through division.

The wide sweep of the book would make even the most critical reader wonder how the system would run without these IAS officers and the scale of performance demanded of them; how important it is to nurture independent thinking and foster, not kill, initiative. It offers a thoughtful road map for serving officers to conduct themselves with professional integrity while maintaining healthy relationships with political leaders. Finally, the book gives sufficient food for reflection on the role of our constitutional, statutory, and regulatory authorities and the role the judiciary has played. Indeed, As Good as My Word ought to be read not only by civil servants, but by ministers, judges, bankers, as well as thinking people in the media, who might benefit from understanding the colossal damage that short-sighted exposés wreak, given their capacity to manipulate public opinion.

The writer is a former secretary, Ministry of Health and former Chief Secretary, Delhi

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05