The best of EYE 2015

We bring to you some of our best pieces from 2015, just in case you missed them, or would just like to revisit with us.

Every weekend, the EYE Sunday special from the Indian Express brings you the best weekend reads. Over 2015, the pages were filled with inspiring stories like that of the Queen of India’s dangals, Divya, who managed to break into — and win — in a man’s world, to stories that capture the oft-ignored realities of India’s populace, even if they are feared, like when our writer spent 23 days with the Maoists in Chhattisgarh.

You see, dear readers, EYE is not just sheets of printed stories, it’s a journey that each of you takes with us, our authors and their muses week after week. And, though, we know you have been following us closely, we bring to you some of our best pieces from 2015, just in case you missed them, or would just like to revisit with us.

The love song of Lorna Cordeiro, the inspiration behind Bombay Velvet

Illustration: Shyam

Illustration: Shyam

In Dhobi Talao today, her name draws a blank—neither the old man selling brun-pav across the road, nor the manager of the Kit Kat cabaret bar know where she lives. I make one last attempt at Snowflake, a popular Goan eatery. The owner’s eyes light up at the mention of Lorna Cordeiro. “She comes here sometimes, for the bombil fry,” she says, excitedly, before giving directions.

Gazdar House, a hundred years old, is symbolic of this Mumbai neighbourhood that has seen better days. If it could, the lobby, with its glossy tiles and grey walls, would conceal the unsteady wooden staircase, the peeling distemper and the smell of dust and mould. On the first floor, at the farthest end of the corridor, the door is open. An elderly woman in a blue printed nightgown bends over a bucket of soaked clothes. I ask her where I can find Cordeiro. She looks up, pushes back her gold-rimmed glasses and says, “I am Lorna.”

Click here to read more.

Revisiting Andha Yug

Ebrahim Alkazi

Ebrahim Alkazi

It was 1963 and India had just lost a war. A man from Bombay turned the ruins of Ferozeshah Kotla into a stage for an epic play about the cost of violence. Ahead of his 90th birthday, we revisit the story of Ebrahim Alkazi, the director with an eye for spectacle, and his production of Andha Yug that changed Hindi theatre forever

What is the right way to tell a mother that her sons are dead? Actor Mohan Maharishi found himself in the role of Sanjay, the messenger of the Mahabharata, who carried the news of the rout of the Kauravas to their parents, Dhritirashtra and Gandhari. “I did not have the emotional resources for this task. I was not able to get what Mr Alkazi was asking for. He was tense. He was always coming around and shaking us up,” says Maharishi about training under the formidable Ebrahim Alkazi. “He was a very exacting man, even with himself. And when he criticised you, he tore your performance to pieces.”

Click here to read more.

When we turn caregivers to parents: Balancing love and duty, ambition and resentment

It was a cold, snowed-in Philadelphia night last December when Sambuddha Chaudhuri, 31, received the phone call. It was his father at the other end, his voice sounding “suddenly very old, very tired”. “My mother, a cancer survivor, had gone for a routine check-up and the doctor found some lumps near her breast. My father had called to inform me that there was a possibility of a relapse,” says Chaudhuri. A decade ago, when he was a medical student at Midnapore Medical College near Kolkata, his mother had been detected with ovarian cancer. “It was in an advanced stage, but she was pronounced cancer-free within a year,” says Chaudhuri.

His mother, Kanika, resumed her job as a professor of education in a south Kolkata girls’ college and Chaudhuri left the country after his MBBS to pursue a PhD on public health from the University of Pennsylvania, US. “When my father called, I couldn’t sleep all night. They insisted that I stay back, but I just couldn’t,” he says. By next evening, he had bought tickets to Kolkata and had that crucial talk with his PhD guide. “Not shifting was never an option for me. I needed to be there,” says Chaudhuri.

Click here to read more.

Girl No.166: Will this retired cop ever stop looking for Pooja?

Even miracles have deadlines, rues assistant sub-inspector Rajendra Dhondu Bhosale. His ended at midnight last Saturday, when the 58-year-old ceased to be the officer on duty, in-charge of the missing bureau at Dadabhai Naoroji Nagar police station, Mumbai. But even in the hours before he retired, he was still hoping for a clue — a detail he might have accidentally skipped, anything, “anything at all” — that would have led him to a little girl named Pooja Gaud.

In the police records, she is a seven-year-old, who went missing on January 22, 2013. She was last seen near her school at 8.15 am. She was wearing a blue pinafore. Between 2008 and 2015, 166 girls went missing in the area under Dadabhai Naoroji police station. Bhosale and his team tracked 165 of them down. Pooja is the missing piece of this jigsaw. And a regret, he says, that gnaws at him every waking hour.

Click here to read more.

Of no fixed address: Mumbai’s street-dwellers are neither beggars nor destitute

Rakhi Jadhav (in yellow) at her home on the Churchgate pavement (Photos: Prashant Nadkar)

Rakhi Jadhav (in yellow) at her home on the Churchgate pavement (Photos: Prashant Nadkar)

Once night falls, the pavement is their home, intruded upon daily by the city that zips by. Mumbai’s street-dwellers are neither beggars nor destitute, but people who have taken a chance on the city, and are looking for a way out.

Rakhi Jadhav lives barely 700 metres from Mumbai’s Marine Drive. Her three children, and the three sons of her alcoholic brother, all love the sweep of the seafront. But the last time they went near the sea was on a Sunday morning, the day of Mumbai’s annual marathon, to collect hundreds of plastic bottles discarded by runners.

Tonight, as the shouts of the streetside vendors and the din of traffic finally subside, Churchgate’s clammy night air is thick with the mingling smells of bhelpuri and sweat. Jadhav, a 33-year-old woman, hurries the children to “bed”, an assortment of plastic chatais, sheets and a mangy mattress spread out on the pavement between Churchgate station’s heritage headquarter building and Cross Maidan.

Click here to read more.

Days and nights in the forest: 23 days with the Maoists in Chhattisgarh

Given rare access, Indian Express reporter Ashutosh Bhardwaj spent 23 days with the Maoists in Chhattisgharh, living in their camps, sharing their food, watching films on a laptop and debating Mao.

In February last year, Ashutosh Bhardwaj gained rare access into the forests of Abujhmaad, Chhattisgarh, a “liberated” Maoist zone run by a network denser than veins in the human body. He spent 23 days in the camps, observing the violence, idealism and deceit that are a part of the guerrilla life. An account of life inside an insurrection.

Click here to read more.

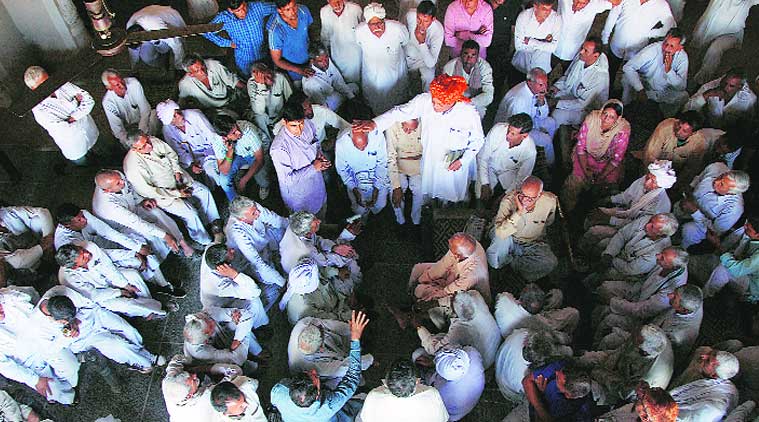

SPECIAL ISSUE | India’s Sons: What does it mean to be a man in India?

What does it mean to be a man in India? What shapes the masculinity of India’s sons? What are the anxieties and entitlements that come with it? A look at some of the answers…

Click here for all the stories.

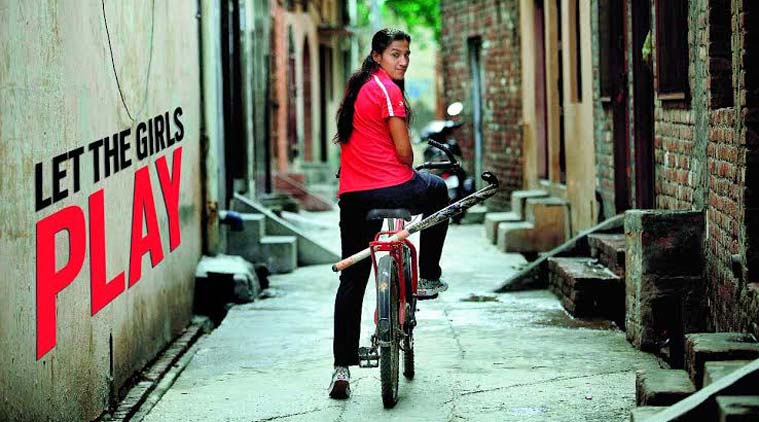

Why Rani Rampal, India’s finest forward in women’s hockey, struggles to survive

Rani Rampal in a lane in Shahabad.

Rani Rampal in a lane in Shahabad.

Situated 200 km north of Delhi on the historic Grand Trunk Road, Shahabad Markanda is a mofussil town of 45,000 inhabitants. If not for its daughters, it would have been one of those tiny dots on Google Maps that you drive past without acknowledging its existence. But you do acknowledge, especially if you have even a remote interest in the sports pages of newspapers. “Ah, Shahabad,” it prompts you to think every time you pass by. This is, after all, the single biggest assembly line of women’s hockey players in India. About 45 players have represented India at senior and junior levels. Shahabad is to women’s hockey what Sansarpur in Jalandhar once was to men’s hockey, or to the cricket-minded, what Mumbai has been to the Indian team.

Click here to read more.

A sex worker duped twice by a ‘friend’

The Road gives her a new name, work and a place to stay, but takes away her child. She is now fighting to get her daughter back. (Source: Praveen Khanna)

The Road gives her a new name, work and a place to stay, but takes away her child. She is now fighting to get her daughter back. (Source: Praveen Khanna)

A 28-year-old woman from a village in Andhra Pradesh ends up in Delhi’s red-light area. The Road gives her a new name, work and a place to stay, but takes away her child. She is now fighting to get her daughter back.

They call it the Road. It starts at Ajmeri Chowk, a few metres from the New Delhi Railway Station and ends at Lahori Gate. It’s here that Farah came with her four-year-old daughter and another waiting to be born. She had boarded the Kerala Express, sat in a “chalu dibba (unreserved coach)” from Tirupati railway station, Andhra Pradesh, and got off at New Delhi. She was then about 28 and it was her first time in the city. She was glad Sharada was with her. She knew so much more, spoke Hindi, lived in the big city and would now help her find a job at the sari showroom where she worked. Instead, Farah ended up on the Road, GB Road — Delhi’s only red-light area.

Click here to read more.

How artists and individuals creatively resisted Emergency

Anant Patwardhan’s film Prisoners of Conscience on political prisoners of the Emergency

Anant Patwardhan’s film Prisoners of Conscience on political prisoners of the Emergency

The dawn of the Seventies. The promise of Independence, and the hope of a socialist, welfare state, stood discredited. A young nation was confronting its inheritance of inequality in many ways. Bombay, like the rest of the country, was simmering with a million mutinies. The Dalit Panthers was formed in 1972, and its firebrand leaders, Namdeo Dhasal and JV Pawar, had called for a revolution to overthrow the caste system. In Maharashtra, Mrinal Gore was steering the women’s movement, with a focus on the daily grind of civic issues. Hardly a day went by without a rally or a protest, without slogans mingling with the sounds of everyday life.

From street plays held in the dead of the night to open rebellion, the story of the cultural resistance to the Emergency is one of many underground movements of artists and individuals.

Click here to read more.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05